How Bezos’ latest plan to protect forests could backfire

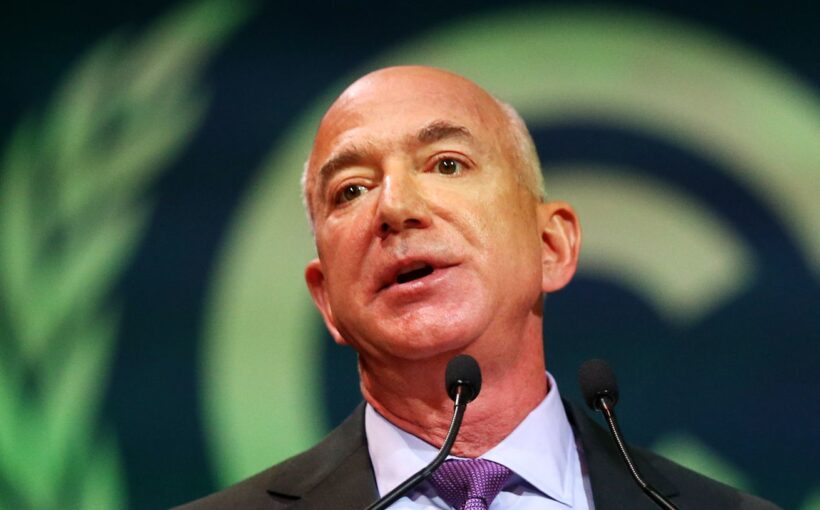

Jeff Bezos’ $2 billion plan, announced last week, to plant trees and restore landscapes across Africa and the US has already raised red flags for some conservation experts and activists. Last year, after he pledged $10 billion to fight climate change, activists in the US called him out for not doing enough to cut down Amazon’s pollution or work with local communities while crafting his environmental plans. This time, he’s facing similar criticisms on a global scale.

The Bezos Earth Fund announced its latest round of funding on November 1 during a high-profile United Nations climate summit taking place in Glasgow. There aren’t many details out yet, but the fund says it will funnel $1 billion towards planting trees and “revitalizing” grasslands in Africa, as well as restoring 20 different landscapes across the US. The other $1 billion will support sustainable agriculture initiatives.

The hope with the new conservation investment is to preserve ecosystems that naturally draw down and store planet-heating carbon dioxide pollution. That builds on a commitment Bezos made in September to spend $1 billion to create and manage so-called “protected” areas for conservation. The Bezos Earth Fund also says it wants local communities and Indigenous peoples “placed at the heart of conservation programs.”

But without safeguards in place, the initiative could potentially harm ecosystems and infringe on local and Indigenous peoples’ rights, some experts say. Instead of flinging money into these projects, they’d rather see Bezos cut pollution from the behemoth businesses he’s founded.

“Organizations like the Bezos Earth Fund have tended to sort of hire people in Seattle to fix Africa. And that doesn’t work,” says Forrest Fleischman, who teaches natural resources policy at the University of Minnesota. “Sort of the best-case scenario [with inexperienced donors] is that they waste all the money, and the worst-case scenario is they do a lot of damage.”

There are heated debates flaring up right now around how to conserve and restore ecosystems. That’s, in part, because of a stream of splashy, new projects to tackle climate change and biodiversity loss. Last year, for instance, the World Economic Forum launched an initiative to plant a trillion trees. That was met with pushback from a cadre of forestry and conservation experts, who warned that aggressive tree-planting campaigns have, at times, led to monocrops of a single species of tree. Those tree farms don’t offer the same kinds of ecological benefits as natural forests that are teeming with diverse species. They might even harm ecosystems by putting a lot of trees where they don’t belong, like in savannas and grasslands.

“Many believe that nothing bad can possibly come from planting trees, but planting trees …in grasslands and savannas does irreversible damage to grasslands and savannas,” Rhodes University ecologist Susanne Vetter wrote in an email to The Verge. Environmental groups like the World Resources Institute have mistakenly mapped those ecosystems as degraded forests suitable for tree planting in the past, Vetter wrote in an opinion paper published in the journal Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems in 2020.

The Bezos Earth Fund said that it will work with AFR100, a partnership between 31 governments in Africa that is advised by WRI and aims to restore 100 million hectares of land across the continent by 2030. AFR100 “advocates actively against the conversion of natural ecosystems, like grasslands and savannas, into tree plantations,” a spokesperson said in an email to The Verge. Each country that’s part of AFR100 ultimately makes decisions based on input from experts and local communities, says Bernadette Arakwiye, a research associate for WRI based in Rwanda. The maps Vetter referenced in her paper have been updated and don’t necessarily inform decisions on which lands to restore, according to Arakwiye.

But splashy climate change commitments like the Bezos Earth Fund can easily fall into pitfalls associated with tree planting because of their focus on speed and scale, says Prakash Kashwan, an associate professor of political science at the University of Connecticut. “Designing restoration projects that are environmentally good requires working with each individual landscape based on what the landscape is like,” he says. “If our goal is to learn from indigenous engagements with nature, one fundamental principle is to slow down.”

Taking the time to consult with local communities who use the land is also important because projects can also inflame old wounds inflicted upon Indigenous peoples in the name of conservation in the past. There’s a history of “green-grabbing” that’s tied to colonization around the world. Half of “protected” areas around the world occupy lands that were once Indigenous peoples’ homes and territories, according to a 2016 report by former United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples’ Victoria Tauli-Corpuz. After land has been set aside as a protected area, tribes might be pushed off their lands or could be barred from practicing traditions like hunting, even when done sustainably.

There’s also a history of violent policing of protected areas. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF), for example, funded park rangers accused of killing, raping, and torturing local and Indigenous people at African national parks and wildlife reserves, a 2019 Buzzfeed News investigation found. In 2020, the Bezos Earth Fund awarded WWF $100 million to protect and restore more lands.

Experts The Verge spoke with have advice for how to avoid repeating the past. “This money should be targeted to wherever, to whatever local communities are already doing and think are the best approaches to [restore landscapes],” says Ida Djenontin, whose research focuses on environmental management and governance at Michigan State University and London School of Economics. Djenontin has also previously collaborated with AFR100. Research has found that forests fare better under the care of Indigenous peoples that depend on them for their livelihoods.

Kashwan is concerned that even if the Bezos Earth Fund is serious about wanting to center Indigenous peoples in its conservation programs, meaningful engagement could be hampered in developing nations that lack a strong, existing framework of legal protections for tribes. “These initiatives are fundamentally flawed because all they do is to [make] declarations of good intentions,” Kashwan says. There’s no institutional mechanism for accountability across much of the Global South, he says.

Even in the US, there’s still work to be done to make sure environmental philanthropy efforts are mindful of vulnerable populations. The Bezos Earth Fund says that 40 percent of funds earmarked for the US will go towards projects that “directly engage or benefit underserved communities.” That comes after grassroots activists pushed Bezos to invest more in communities of color disproportionately burdened with pollution. Some of those communities are still fighting for Amazon to clean up the air pollution its warehouses saddle their neighborhoods with.

Experts tell The Verge that perhaps the biggest impact Bezos could have would be to stop the harm Amazon does to the environment through its pollution. Even after making big pledges to tackle climate change, Amazon’s greenhouse gas emissions have continued to grow in recent years. As long as that’s the case, initiatives like Bezos Earth Fund amount to little more than corporate greenwashing, say experts like Fiore Longo, head of the conservation campaign at Survival International, a human rights organization that advocates for tribal peoples.

Wealthy corporate figureheads, she says, “think they can just keep destroying the planet through producing emissions and then creating protected areas or planting trees somewhere and then magically, their emissions will be compensated for. In the key moment that we are in when we need real decisions for the protection of biodiversity and to stop climate change, we can’t allow ourselves this kind of distraction.”

The Bezos Earth Fund declined The Verge’s request for comment.