Head to London’s West End and you are likely to find all sorts of plays for families, inspired by some of the most loved children stories. There is JK Rowling’s Harry Potter And The Cursed Child, Neal Foster’s adaptation of David Walliams’ Gangsta Granny and Tim Minchin’s “anarchically joyous, gleefully nasty and ingenious musical adaptation” of Roald Dahl’s Matilda, as theatre critic Lyn Gardner described it.

The popularity of theatre for children and for adapting children’s books for the stage begins in Britain with the works of best-selling children’s writer Enid Blyton (1897-1968) in the 1950s. By this time Blyton had, as The New York Times reported, made herself “supreme above all authors” and was “a category all herself”. This was thanks to her long-running magazine Sunny Stories, adventure series such as The Famous Five and The Secret Seven, and stories set in the boarding schools Malory Towers and St Clare’s. It was not unusual for bookshops to have a designated Enid Blyton section due to her regularly publishing 30 or more books a year – 39 in 1951 and 44 in 1952.

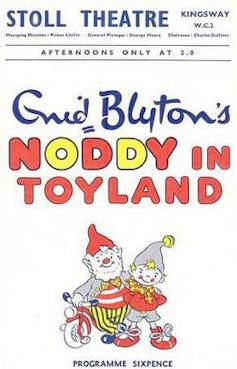

It made sense, then, to adapt her stories for the stage and she sometimes had two shows running in London during the Christmas season: Noddy in Toyland (1954-59) and the thriller Famous Five Adventure (1955; 1956). The importance of Blyton’s literary achievements remains a contentious issue but in the 1950s she mostly seemed untouchable and conquered the West End as seamlessly as she had done the world of children’s publishing.

This was especially so with Noddy in Toyland (described as a “pantomime”), which opened on December 23 1954. Along with the power of Blyton’s name, Noddy’s catchy tunes, dazzling special effects (including a “real” train puffing steam on stage) and the ease with which Blyton’s characters could be shoe-horned into a familiar pantomime plot (the usually timid Noddy travels to the Enchanted Wood to capture some wicked goblins) helped make it a West End fixture.

Noddy on Stage

Noddy, a little wooden nodding boy who lives in Toyland, first appeared in the stories Noddy Goes to Toyland (1949) and Hurrah for Little Noddy (1950) and came to be Blyton’s most famous character. There were 24 tales in the “Noddy Library” series, ending with Noddy and the Aeroplane (1963).

The Noddy books’ success was due in part to the colourful illustrations by Dutch artist Eelco Martinus ten Harmsen. Designed for pre-school children, the books’ characters were partly intended to compete with those of Disney and were an enormous hit in Britain. By 1962, 26 million copies of the books had been sold.

In 1954, When the wooden boy made his stage debut it was, unsurprisingly, a hit.

Children at performances reacted noisily and excitedly. They leaned dangerously over the balconies to get a better look and tried to grab the sweets thrown to them from the stage. It was often pandemonium but to Blyton, this did not matter: “the children took over the play at times and even held up the action”, she reported proudly.

Noddy came at a time in the history of pantomime and theatre for children as it coincided with celebrity casting taking off, much to the annoyance of traditionalists. “If this is the way pantomime is going’, remarked one reviewer faced with the crooner Frankie Vaughan, “it will speedily become a yearly parade of television performers going through their usual paces … [and] there will be little point in taking the children along”.

Blyton was widely credited with returning pantomime to children. Her plays had no “stars” but sold out nonetheless.

The familiarity of the characters was part of the appeal of Noddy and later the Famous Five Adventure – in much the same way that Harry Potter and Matilda draw audiences in 2021.

Critical plaudits

In 1954, people worried about declining theatre attendances (partly because of the threat posed by television) held up Noddy in Toyland as proof that the way to make children develop a long-lasting interest in theatre, and thus ensure its survival, “is to offer them real plays of their own” (The Stage, December 31, 1954). Even writer Kenneth Tynan – a fearsome enemy of things twee and formulaic – used his Observer column to compare the “pleasing” production favourably against the star-studded pantomimes elsewhere, full of “radio comedians…condemned to fidget uneasily in doublet and hose” (26 December 1954). As Tynan noted, Noddy in Toyland kept things simple.

Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

Simplicity was, of course, part of the charm of Blyton’s work. The show was easier to follow than other pantomimes. Fairies, goblins, talking animals, humans and toys came together in a world that made sense to its young audience. But as reviewers noted, there was a myth-like quality to it all. The show promised an exciting but easily understandable way of living beyond the every day, which even to young children who (one might suppose) had not lived long enough to become jaded, was beguiling.

Blyton’s plays have been forgotten but 70 years on this is still part of the appeal of such shows. In Blyton’s case, it is another instance of her legacy – a legacy that sits awkwardly in the history of popular entertainment.

![]()

Andrew Maunder does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Source: TheConversation