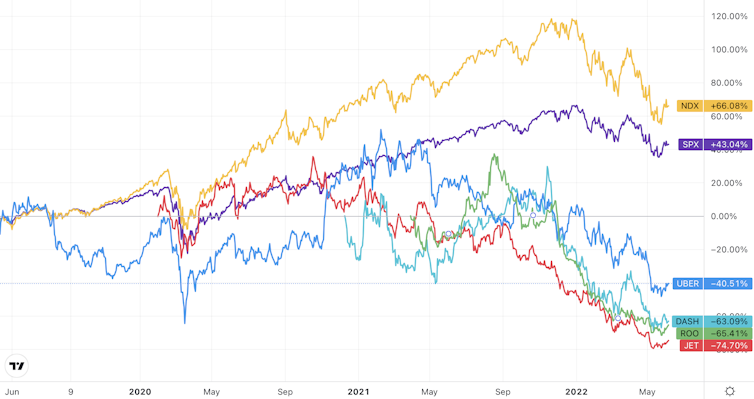

They rose to great heights but have been falling back hard. The share prices of companies in the so-called gig economy have been performing abysmally, even compared to the woes of stock markets in general. This dates back some 18 months though it has intensified since last autumn.

Uber, known for ride-hailing and takeaway food delivery, is now valued at US$49 billion (£39 billion) compared to US$125 billion-plus in early 2021. DoorDash, a US takeaway delivery firm, is down to US$28 billion from nearly US$90 billion over the same period.

Just Eat, which delivers takeaway in the UK, Europe and US, has fallen from a valuation high of £24 billion to under £5 billion. It is trying to sell off GrubHub, a US business it bought for US$5.9 billion just two years ago. Meanwhile, Deliveroo, another UK takeaway company, has seen its valuation fall from £7 billion to £1.7 billion in only nine months.

Gig economy companies vs S&P500/Nasdaq-100

TradingView

The legendary investor Warren Buffet supposedly once said that “you don’t find out who’s been swimming naked until the tide goes out”, and this has never been more appropriate than for these gig economy companies. The share sell-offs will vastly reduce the flow of funds into the sector, making borrowing more difficult and putting added pressure on companies to repay existing debts.

So what has caused the collapse and what does it mean for workers and consumers?

1. Money is no longer easy

We’ve been living in an era of low interest rates and high demand for corporate debt, which has seen investors driving high-growth “technology” industries to astronomic heights. It is highly debatable whether ride-hailing or takeaway food are really technology businesses simply because they have an app, but the markets have certainly chosen to treat them that way.

The pressure on these companies to achieve high growth to feed this investment frenzy has incentivised gig businesses to underprice their services while offering attractive rates of pay to bring in riders and drivers.

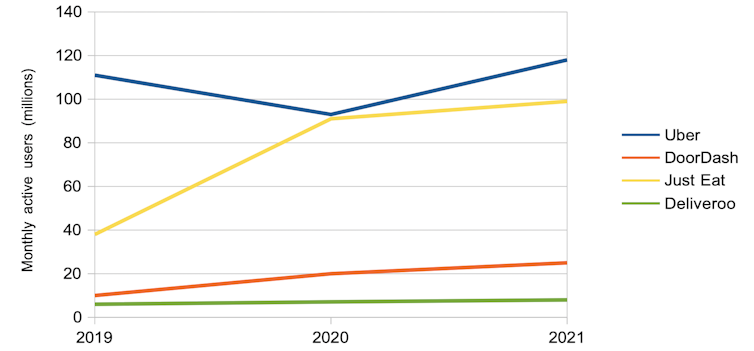

The objective has been to create what are known as network effects. Some businesses are seen as networks, which essentially means that the users interact with one another – classic examples are telephone networks and social media platforms. Networks become considerably more valuable the more users they have, since they become more and more useful to each user as a result.

In gig economy businesses, the logic has been that the more customers they can attract, the more riders and drivers will be attracted. High demand will provide these riders and drivers with more work and less unpaid waiting, and this in turn will make the business more responsive to customers, so more and more of them sign up.

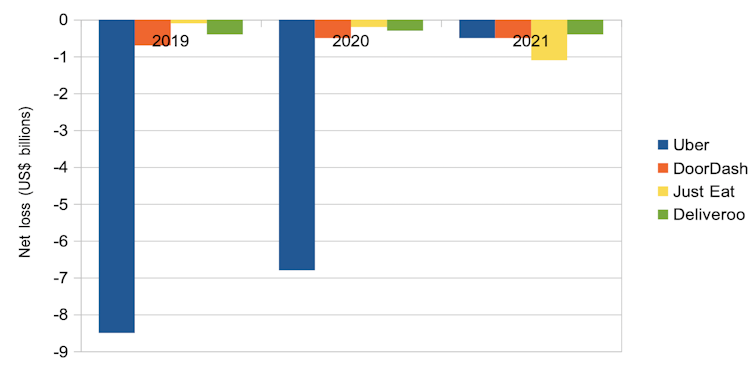

The objective for each company has been to kill off all the competition, just like Amazon has done and Facebook did for a while. This has resulted in enormous losses for virtually all gig participants. While credit was easy, they were confident they could continue attracting new investment to fund these losses so long as customer bases were growing, but not so anymore.

Net losses by company (US$ billions)

Various

2. Demand woes

Now that investors are no longer so willing to fund losses, gig firms are having to become self-funding by reaching at least breakeven. To do this, they are having to increase prices at a time when customers have got less disposable income because their wage increases are not keeping up with inflation. Uber, for instance, raised its fares by 10% in London near the end of last year.

The high rates of inflation may well continue for, say, the next year or so. If so, it is likely to keep squeezing people’s disposable income. We have already seen Netflix subscribers falling as consumers make decisions to economise and save on their streaming costs, and unfortunately, the gig firms are offering services where there are often alternative options available.

Customers can often choose to collect takeaways or walk to the supermarket rather than pay the extra for delivery. They can often take public transport or cycle rather than hailing a taxi. Reduced demand for their services is almost inevitable as a result.

3. Downward spiral

The other side of the coin for these firms is that they are having to cut costs, including reducing benefits to workers and keeping a tight control on wages. This will make the work less attractive for these self-employed people, and what was previously an unlimited supply of riders and drivers will be tightening.

As a result, these relatively low paid people might pursue better-paid work elsewhere – we recently saw delivery drivers in parts of England effectively going on strike in demand of higher wages. At the same time, customers have already been complaining about service in some instances. The poorer the quality of service, the more that demand is likely to drop.

As competition intensifies in the sector, only the strongest will survive. Some firms will disappear and others will be taken over.

Monthly active users by company (millions)

Various

The breadth of services will also probably reduce. Many of these gig services are only likely to be long-term profitable in more affluent areas, where customer demand is likely to hold up at higher prices; and areas of high population density, since the model becomes more attractive to everyone when drivers and riders wait less time for their next job.

In the UK, for example, this would point to the more affluent parts of London and Manchester – if the business model is viable anywhere at all. In effect, a long-overdue correction to the gig economy is taking place. How it emerges on the other side is still anyone’s guess.

![]()

John Colley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Source: TheConversation