Around 1.5 million Ukrainians have settled in Poland in the aftermath of the full-scale Russian incursion of Ukraine in February 2022. This is in addition to the 1.3 million that arrived after the 2014 annexation of Crimea. The latest group comprises mainly women and children, in contrast to those already there who were predominantly male and economically active.

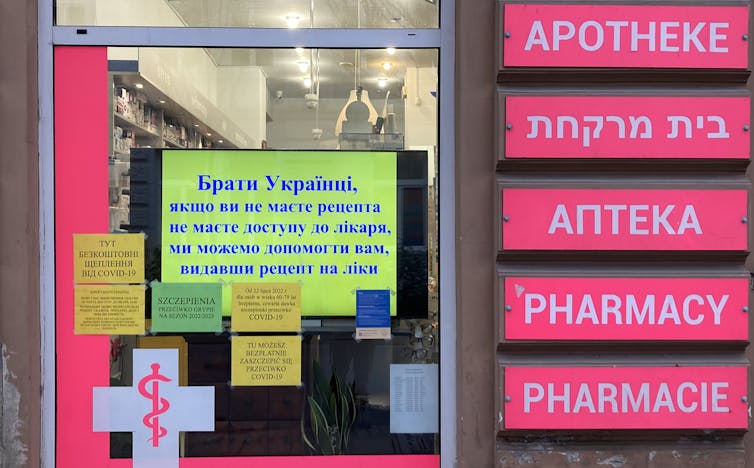

Ukrainians now make up 3% of Poland’s population, whereas Poland was until recently practically mono-ethnic, with only a small number of minorities or refugees. Today Russian and Ukrainian can be heard on every major Polish street and the two languages have become part of the public landscape.

Piotr Goldstein, Author provided

But the relationship between Poland and Ukraine is filled with tensions. Among them are diverging views on key historical events and figures. For example, the appointment of Ukraine’s former ambassador to Germany, Andrij Melnyk, as deputy foreign minister in November could cause friction between the two countries.

Melnyk caused an uproar in Poland earlier in the year when he claimed that the controversial Ukrainian nationalist leader Stepan Bandera “was not a mass murderer”. For many Poles, the killings in Volhynia that took place between 1943 and 1945 under Bandera’s leadership of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army are regarded as genocide. The lower house of the Polish parliament, the Sejm, recognises them as such.

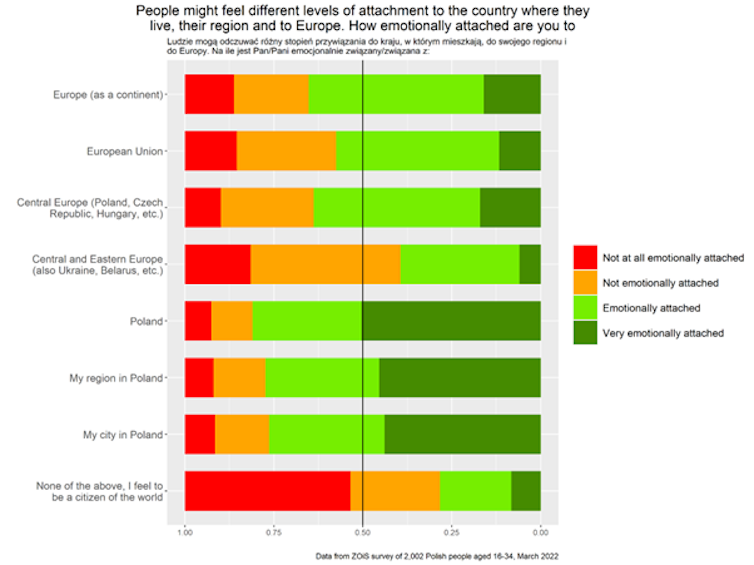

Central and eastern Europe’s contentious history is significant for understanding today’s Polish solidarity with Ukraine – and the challenges this solidarity faces. To explore this topic, the Berlin-based Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS) conducted a survey in early 2022 among young Poles aged 16-34, and focus groups among young Poles and people over the age of 65, to understand the diverging reactions to the war in Ukraine among those born after the fall of the Soviet Union and those socialised during the communist era.

Qualified solidarity

The visibility of Ukrainians builds on a gradual change in Polish society that occurred during nearly a decade of solid economic growth. Since 2017, the unemployment rate in Poland has been low, oscillating at around 7%, due both to economic growth and mass emigration after Poland joined the EU in 2004. As a result, Poland has experienced a significant shortage of labour across economic sectors.

In our focus groups, the older generations in particular stressed the economic benefits of Ukrainian immigration – filling gaps in the workforce and contributing to the pensions system. Young respondents, by contrast, were more likely to mention increased competition over scarce resources such as access to childcare or healthcare.

The solidarity that Poles express vis-à-vis the overwhelmingly female Ukrainian refugees who have arrived since the February invasion also differs between age group, economic status and gender. The young respondents to our survey expressed a strong solidarity with this later wave. In March 2022, 50% said Poland should let as many Ukrainians into the country as would be necessary.

As well as the difference in gender between refugees arriving this year and those who came after the 2014 annexation of Crimea, the new arrivals have a markedly different socioeconomic profile. Before 2022, Ukrainians arriving in Poland responded to gaps in the country’s labour market, taking jobs with low social status. This has been reflected in the Polish vernacular: a middle-class resident of Warsaw referring to “a Ukrainian woman” usually means a cleaner.

But now, many Poles are surprised that Ukrainians don’t seem to fit this stereotype of Ukrainian refugees as poverty-stricken people willing to take any job. The fact that some Ukrainian refugees are better off than the average Polish citizen has also led to confusion in the host country.

In our focus groups, some Poles complained about rich Ukrainians while others appreciated the newcomers’ hard work and entrepreneurship. There are still signs of solidarity between the two populations – but increasingly Ukrainian refugees are seen as a burden.

Which eastern Europe?

The solidarity with Ukraine also challenges another stereotype: a geographical one. Many Poles, especially young survey respondents, said their neighbour belongs to a “different” eastern Europe to the one with which they are more likely to identify – an eastern Europe which comprises Hungary and Czechia rather than Ukraine and Belarus.

Félix Krawatzek and Piotr Goldstein (ZOiS), Author provided

Poland and Ukraine have a complex historical relationship. This can perhaps best be seen in Polish attitudes to the people who live in border ares once controlled by the Poles. Many Polish people still refer to these regions as “Kresy” – “[Poland’s eastern borderlands”]. So while Poles think of their Ukrainian neighbours as “brothers” – sharing a Slavic heritage and centuries of common history – this attitude often comes with a mixture of nostalgia and a faintly neocolonial attitude.

A conflicting relationship

Poland has changed profoundly in the past ten months. As Ukrainian newcomers try to establish their lives in Poland, their presence has raised completely new questions for Poles. What to do with talented Ukrainian high-school graduates blocked from accessing free higher education because of their insufficient Polish language skills? Will the Ukrainians have political representation in Poland – and, if so, who will fight for it?

In the run-up to the 2023 parliamentary elections in Poland, the topic of solidarity and the long-term participation of Ukrainians in Polish society is likely to be an issue of some debate. Thus far, the populist conservative Law and Justice (PiS) governing party has not addressed the topic.

How the debate will play out depends on how Ukrainians get involved in Polish society and whether their participation is considered valuable by native Poles. Limits to solidarity are visible – maintaining it requires a daily commitment from all sides.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Source: TheConversation