Paul Anderson is a former editor of and columnist for Tribune.

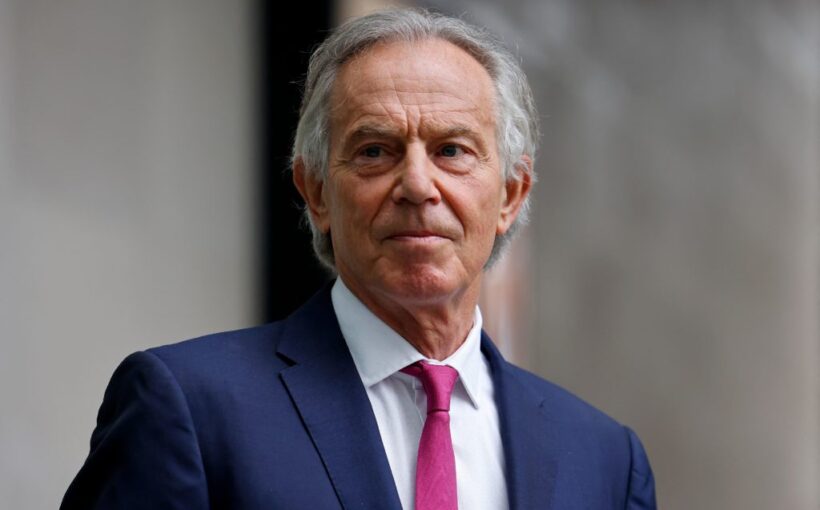

It’s not unusual in British politics to observe that Labour leader Keir Starmer is channeling former Prime Minister Tony Blair — the last leader from his party to win a general election.

Supporters of Starmer’s hard-left predecessor Jeremy Corbyn started calling him a Blairite as soon as he stood for leader — and not as a compliment. And as he has slowly but surely shifted his party toward the center, Starmer has undoubtedly echoed Blair’s pre-1997 opposition rhetoric — Labour as the “political wing of the British people” and so on — as well as adopting much of the strategic playbook of 1990s “New Labour.” Though no one expects the New Labour branding to be fully resurrected, the party will fight the next general election proclaiming its modernity, business-friendliness, fiscal responsibility and Atlanticist foreign policy — just as in 1997.

New Labour was about more than just Blair, however, and his direct personal influence on Starmer today is hard to pin down. Starmer says the two talk, but the former leader has played no public role in his operation beyond a couple of brief endorsements.

By contrast, the other key architect of 1990s New Labour, Gordon Brown — finance minister from 1997 to 2007 and prime minister from 2007 to 2010 — has become ever more prominent in both guiding Starmer and formulating policy and strategy.

Brown’s most important service for Starmer so far has been to chair an ad hoc committee, the Commission on the UK’s Future, which published a blueprint for constitutional change last month. Launched during the football World Cup in Qatar, the report had little immediate media impact except in Scotland — but its significance is potentially massive.

Under its proposals, Britain’s House of Lords — the unelected upper house of parliament — would be replaced by a smaller “democratically legitimate” second chamber. Government would be radically decentralized to the United Kingdom’s nations and regions, with a big increase in the clout of the Scottish and Welsh parliaments, as well as the devolution of key powers to English towns, cities and regions. Civil servants would be relocated out of London.

Starmer described it as the “biggest ever transfer of power from Westminster to the British people.”

Hyperbole? Perhaps.

Predictably, the Scottish National Party (SNP) and the Tories dismiss Brown’s scheme as a damp squib, and Labour peers grumble that removing them isn’t a priority. Meanwhile, others recall the unhappy recent history of Lords reform all too well: Blair botched Labour’s goal of removing all hereditary peers in 1999, and backbench Tories forced then Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron to abandon plans for a largely elected second chamber in 2012.

Labour also remains haunted by the way its scheme for English regional devolution was scuppered by voters in the northeast of England in 2004, who voted 78 percent to 22 percent against a regional assembly in what was meant to be the first of many referendums. (The populist “no” campaign was masterminded by the young Tory Dominic Cummings, who later became director of “Vote Leave” during the 2016 Brexit referendum and was the controversial chief adviser to former Prime Minister Boris Johnson from 2019 to 2020.)

Perhaps most important, however, is that the Brown report is a first draft, full of ambiguities, and it’s now out for consultation, which could be tortuous: There’s no guarantee a version of it will make Labour’s next manifesto.

Nevertheless, Labour is currently making a big thing of it. Party strategists think it could be key to wooing former supporters who deserted to the SNP in Scotland (mainly after the 2014 independence referendum) and to the Tories in many English urban areas (mostly over Brexit); voters who felt ignored by distant and unaccountable bureaucracies, in London and Brussels respectively.

Their big idea is to wrap the package up in the stolen Tory Brexit slogan “Take Back Control” — and hey presto!

As Starmer put it in his New Year’s speech: “As I went around the country campaigning for Remain, I couldn’t disagree with the basic case so many Leave voters made to me . . . It was the same in the Scottish referendum in 2014 — many of those who voted ‘yes’ did so for similar reasons . . . The control people want is control over their lives and their community. So, we will embrace the Take Back Control message. But we’ll turn it from a slogan to a solution.” A “Take Back Control” bill, he said, would be a legislative priority in government.

Whether this will prove to be inspired rhetorical larceny is unclear. It’s quite possible the slogan won’t hit a nerve with voters. But if it does, and Starmer thrashes out the details and wins comfortably in 2024, there’s no reason Labour couldn’t act as decisively as it did when it steered Scottish and Welsh devolution in 1997.

After 1997, he biggest obstacle to Labour pushing harder for Lords reform and English regional government was simply Blair’s own chilliness to the idea — Brown and his fellow long-time supporters of constitutional reform could never overcome it. And though he tried to revive the project when prime minister, he was too busy dealing with the 2008 financial crash to pursue it.

It’s clear that now Brown sees this as a last chance to complete unfinished business — and with Starmer, he’s pushing at an open door. It would be a surprise for Brown to return to parliament to see it through. But then again, who knows?

Source: Politico