Welcome to the UK, where affordable housing can often feel like an oxymoron. The average national house price is £294,000, but someone earning the average annual salary of £33,000 can expect to borrow no more than £140,000, leaving a considerable shortfall. The typical first-time buyer is aged 32 and pays a £54,000 deposit for a £264,000 house, which is clearly out of reach for many people.

New builds make up about a fifth of the market. They are a particular issue for affordability, since they command a premium of about 10% over an existing home for the convenience of being new. But is this justified?

Housebuilders tend to blame things like the planning system, the costs of materials and labour for elevated prices. It’s also popular to blame land prices. The FT’s chief economics commentator, Martin Wolf, told the House of Lords Select Committee on Economic Affairs in 2016 that “it must be the case” that different land values for different uses are a “fundamental factor in determining the price of housing”.

The evidence to back up this kind of claim is hard to find. There is no single dataset or source that gives, for example, the land price for each new-build home sold, or any register of the price of land used for a development.

Our latest research project sought to overcome these difficulties by comparing various sets of housebuilding data. Our findings indicate that none of the usual explanations are accurate. Instead, housebuilders appear to be making ever greater profits.

Our work

Our research compared 22 publicly available national datasets, looking at the period between 1998 and 2020. One of the datasets is known as gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) of new homes, which is published by the Office for National Statistics and reflects the sale prices of new houses minus the land prices. It includes the costs of things like labour, materials and subcontractors, plus whatever profit the builder makes from the sale.

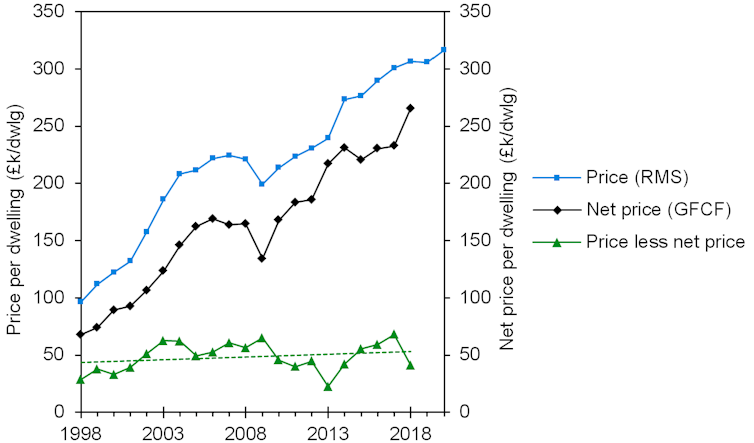

We were able to calculate land prices by working out GFCF per new dwelling and deducting this from the average price of new houses in a given year. This clearly demonstrated that the land price per house has flatlined since 1998 at £48,000 per home, per the graph below (land prices are the green line).

New house prices vs land prices

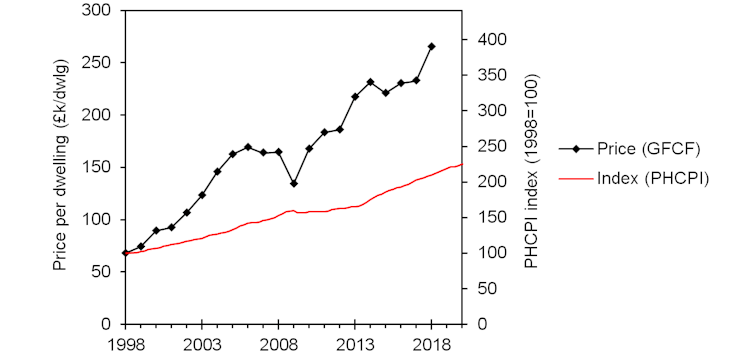

We also compared GFCF per dwelling to the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors’ (RICS) index. The index reflects what it costs housebuilders to rebuild a defined standard house, including adding a reasonable rate of profit on top. This is used by insurers to make sure that homeowners’ premiums for buildings insurance reflect the cost of a rebuild.

In other words, GFCF per dwelling is broadly to new builds what the RICS index is to rebuilds. There is the additional complication that RICS is based on a “standard” house and not an average of the costs of all new houses, but it’s still a useful rough comparison. It shows that the RICS index doubled between 1998 and 2019, while GFCF per dwelling quadrupled.

New build vs rebuild costs

To get a better understanding of the forces at play, we had to account for the cost of materials and labour. We also accounted for any changes over the years to the size of a new build compared with the RICS “standard” house, and other things that could make new builds more expensive such as carbon reduction requirements.

We found that building costs including labour have only increased marginally once you account for inflation. Meanwhile, the floor area per new private dwelling has remained static. The new housing product and process of construction have barely changed since the late 1990s. As for carbon reduction, thermal losses per home fell by about a quarter from 2009 to 2013, reflecting changes in new-build requirements that will have affected costs, but have has since been static and certainly won’t account for the overall trend of increasing prices.

In other words, the difference between the RICS index and GFCF per dwelling is largely explained by an increase in housebuilders’ profits. According to our calculations, their profits per dwelling rose £75,000 between 2000 and 2019. Interestingly, this was quite close to another piece of research from 2021 that looked through the company accounts of the nine largest UK housebuilders and found that their pre-tax profit per house sold rose from about £6,000 in 2009 to £63,000 in 2017. UK Housebuilders’ pre-tax profit margins currently range from between about 12% and 30%.

Consequences

If you are thinking that the market might take care of this profits issue now that interest rates are going up, don’t be too optimistic. Prices have certainly cooled slightly in recent months, but most analysts assume this is temporary and that prices will resume climbing before too long.

So what should be done? The UK government’s recent responses to high house prices have included launching the First Homes scheme supporting first-time buyers, and creating a first-time buyer tax-free savings product. But instead of only addressing borrowing, there needs to be more emphasis on new-build prices. We would like the government to publish data on housebuilding net of land price to make it easier for everyone to see how the average cost of construction per home has changed.

Housebuilders’ high profits also suggest they have ample funds to maximise thermal efficiency and provide other sustainability features in new homes. Energy efficiency in new builds has not improved in a decade, with still only a small proportion built to the highest energy performance standard.

Then there is the fact that not enough new homes are being built. In the year to March 2022, the 204,530 new houses and flats were well short of the government’s 300,000 target, and this is a long-term problem. There are arguably parallels with the energy market in which a shortage of supply has elevated prices and enabled suppliers to make large profits.

A house is most people’s single largest purchase, so clearly prices have consequences for society. Everything in our findings suggests that there may be a case for a government investigation into the performance and structure of the new-build market.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.