Productivity in the UK over the last 15 years has been described as growing at a “snail’s pace”. Meanwhile, wages lag way behind inflation, and numerous sectors are suffering from staff shortages.

One thing that connects these three economic issues is poor job quality.

Job quality is not just about pay. It also about elements that can be difficult to measure, such as security, autonomy, work-life balance and opportunities for progression.

All of these can improve a worker’s wellbeing, and provide a sense of satisfaction, which improves productivity and reduces absenteeism. As one team of researchers concluded: “Good jobs are important contributors to health and wellbeing; conversely, poor job quality piles costs on to the health system and the economy”.

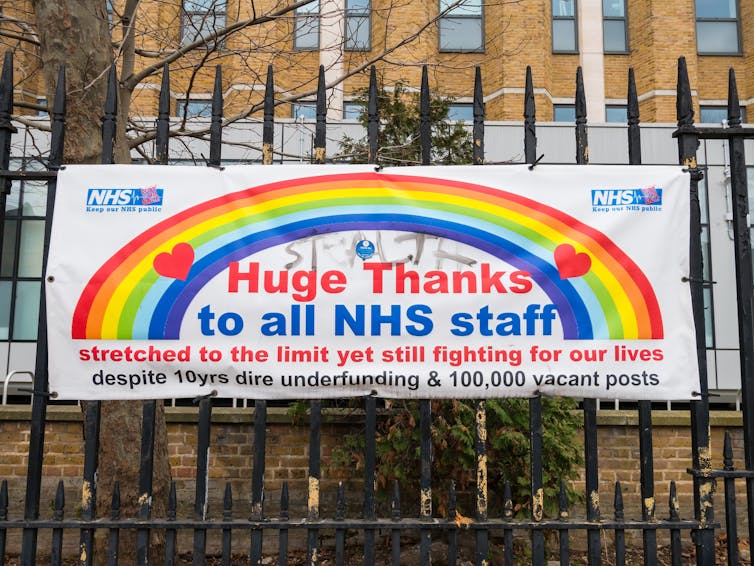

These costs can be clearly seen as the UK faces the highest rates of industrial action for several decades.

The causes of these strikes – by doctors, nurses, teachers, civil servants, transport workers and university academics – are complex and varied. But broadly they are happening because the strikers desire jobs of higher quality. They want secure employment without wage stagnation and without worsening conditions and benefits.

The staff shortages across the UK economy are also complicated. One view is that they are mainly driven by structural changes in the labour market, such as a relatively high number of people retiring early, and a post-Brexit decline in migrant workers.

But another factor is a diminished tolerance for poor quality jobs. Surveys last year found that one in three public sector workers were contemplating quitting their jobs because of low pay and poor conditions.

Research suggests that if the quality of a job is considered low, a worker has three options: they can quit; they can express their discontentment (by striking, for example); or they can choose to remain silent and tolerate their situation.

It seems that the last option is becoming less and less popular. Instead, more workers are either opting to leave – contributing to staff shortages – or take industrial action.

So improving job quality seems like a good way of fixing the significant problems facing the British labour market. But how can this be done?

One option is “collective bargaining”, which allows groups of workers, nurses or teachers for example, to negotiate an agreement with the many employers who determine what they get paid. This establishes common wage rates for all workers in a particular occupation or sector.

Research suggests that sector-wide negotiations of this type can be effective in creating a high minimum standard of wages. This in turn compels employers to compete with others on quality and productivity, rather than by lowering labour costs.

In many countries governments play a key role in the collective bargaining process by establishing rules about how it operates, and what powers are available to unions.

Working together?

In Denmark for example, sector-wide bargaining over pay, conditions and training is part of the country’s high-wage, high-skill, high-productivity economic ambitions. And research indicates that so far its approach is achieving better outcomes not only for workers, but also for businesses.

The Danish model stands in stark contrast to the UK, where the practice of collective bargaining has been weakened, and where successive governments have introduced laws designed to make it harder for workers to strike.

Yet this solution is aimed at the symptom of the problem, not its cause. If poor job quality is not addressed, workers’ discontent will continue.

Elsewhere, a 2019 report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development found that countries with coordinated systems of sector-wide bargaining had better job quality outcomes, “higher employment, lower unemployment … and less wage inequality” than those without. The EU’s new minimum wages directive now obliges member states to increase collective bargaining coverage across their work forces.

It’s one thing for these reforms to be implemented in Europe, which has traditionally been more accommodating of collective bargaining. But it’s another thing to contemplate them in countries where collective bargaining has been actively dismantled.

However, two countries with similar legacies have recently embraced sector-wide bargaining. The New Zealand government has introduced “fair pay agreements” negotiated between employer associations and unions that set minimum terms and conditions for all employees in a given sector or occupation.

The agreements must also contain measures relating to benefits, working hours, and training and development. And last December, the Australian government passed laws making it easier for workers to collectively bargain with employers.

In the UK, problems with job quality underpin both the immediate challenges of industrial action and staff shortages, and the more enduring problems of low productivity and low wage growth. The international evidence points to sector-wide bargaining as the most effective way improve the UK’s economy – and people’s working lives.

![]()

Chris F. Wright has previously received funding from the UK, Dutch, Australian and New South Wales governments, the International Labour Organization, and various employer and trade union organisations.