Despite a surge in interest in craft beers and ales, lager continues to dominate global sales, with more than 150 billion litres consumed around the world every year.

Lager is a beer brewed at low temperatures using yeast that are described as “bottom-fermenting”. Yeast are single-celled fungi used in brewing to convert maltose to alcohol and carbon dioxide, giving beer its booziness and fizz. They are either top- or bottom-fermenting.

In top fermentation, which occurs at warmer temperatures, the yeast cells collect near the surface of the fermenting liquid. In bottom fermentation, which occurs at cooler temperatures, the yeast is carried to the bottom of the fermenting liquid. Ales (which pre-date lager) have traditionally been made using the top-fermenting yeast species Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

The origins of the bottom-fermenting lager yeast Saccharomyces pastorianus have long been shrouded in mystery and controversy. However, by combining historical research with modern science, a team of scientists from the Technical University of Munich and University College Cork (including myself) have uncovered the likely genesis – and path to world dominance – of S. pastorianus.

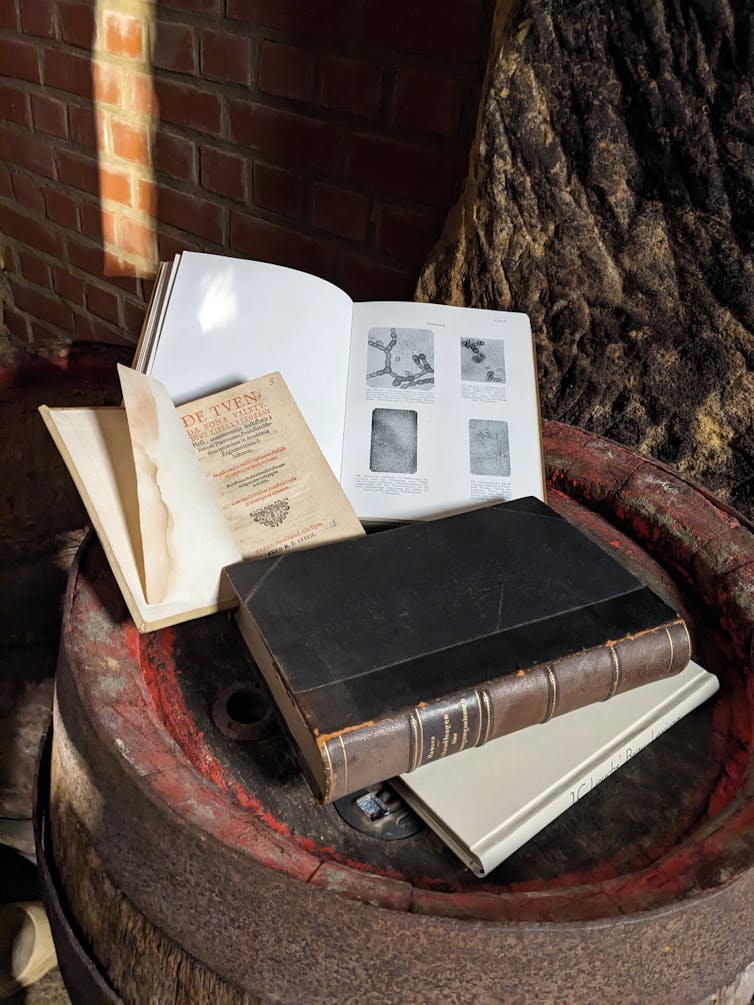

This discovery started with the study of old central European brewing records by the Munich-based scientists Franz Meussdoerffer and Martin Zarnkow. It’s a tale of power, economics, science and innovation – with some sex thrown in for good measure.

But in short, the mating of the yeast species S. cerevisiae from Bohemia with the Bavarian yeast Saccharomyces eubayanus in Munich at the start of the 17th century gave rise to the first lager yeast strain.

Until now, prevailing wisdom had been that the emergence of bottom fermentation in brewing coincided with the genesis of S. pastorianus. However, among many intriguing discoveries in our new report in the journal FEMS Yeast Research is the finding that bottom fermentation in southern Germany pre-dated the birth of S. pastorianus by at least 200 years.

In fact, bottom fermentation originated in northern Bavaria. Not only was it common practice in this part of Germany, but the Bavarian Reinheitsgebot brewing regulations of 1516 only permitted bottom fermentation. Thus, from at least the 16th century onwards, Bavarian brown beer was produced by mixtures of different bottom-fermenting yeast species known as “stellhefen”.

Exception to the rule

These mixtures were dominated by yeast that preferred the lower temperatures that prevailed in Bavaria at this time, a hangover from the medieval little ice age. Meanwhile the historic region of Bohemia, to the northeast, was under different political rule. Here, ales – including wheat beer – were produced with a preference for the top-fermenting species S. cerevisiae.

The 1516 Rheinheitsgebot barred Bavarians from brewing wheat beer, which led to a vibrant export market in the wheat-based beverages from Bohemia to Bavaria. This resulted in a loss of income to the Bavarian nobility who controlled brewing. Eventually, in 1548, the nobleman Hans VI von Degenberg was granted the privilege of brewing wheat beer in Bavaria, and his family built a famous wheat brewery in the town of Schwarzach.

But privileges needed to be protected. When Hans VIII Sigmund von Degenberg, grandson of Hans VI, died without an heir in 1602, his property, including the brewery, was seized by Maximilian I, then duke of Bavaria and later prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire. Historical records show that on October 24 1602, top-fermenting yeast was brought to the duke’s Hofbräuhaus brewery in Munich where, at the time, the brewing of wheat beer alternated with the making of traditional barley-based Bavarian brown beer.

Top to bottom

My colleagues and I propose that, by the time a dedicated wheat beer brewery had opened in 1607, yeasts from within the top-fermenting Schwarzach wheat beer yeast mixture and the bottom-fermenting Munich Hofbräühaus stellhefen had mated, creating the new species we now know as S. pastorianus. Thus, sex in a beer cellar created the direct ancestor of all modern lager yeast strains.

This theory is consistent with published genetic evidence showing that the S. cerevisiae parent of S. pastorianus was closer to ones used to brew wheat beer than strains used for barley-based ale.

That is not the end of the story, however. Two hundred years later, in 1806, the recruitment by the Munich Hofbräuhaus of a new master brewer, Gabriel Sedlmayr the Elder, transformed the world of beer forever.

Although Sedlmayr resigned and purchased the Oberspatenbräu brewery after only a year, he took yeast mixtures with him and established a very successful brewing system based on technological innovation and links to local academics.

Later known as the Späten breweries, the enterprise begun by Sedlmayr became a centre of excellence that attracted brewers from all over Europe, who returned home with the Munich technology – and its yeasts. Among them was J.C. Jacobsen, founder of the Carlsberg brewery, who took the Munich stellhefen back to Denmark’s capital Copenhagen in 1845.

It was there, in 1883, that Emil Christian Hansen isolated the first pure strains of S. pastorianus. Jacobsen and Hansen of the Carlsberg brewery, Gabriel Sedlmayr the Younger, and Luis Aubry, a brewing scientist and microbiologist at the Munich Research Station, shared a friendship based on a passion for beer and progress. This contributed to some fertile scientific and technological exchanges between them.

Not long afterwards, the German scientist Paul Lindner, working at the Berlin Institute, also isolated S. pastorianus from mixtures derived originally from the Späten breweries, which were now in wide circulation among Munich breweries.

All modern lineages of S. pastorianus can be traced to the work of Hansen and Lindner, and so are ultimately descended from the Hofbräuhaus stellhefen.

Further intrigue followed, including bitter inter-brewery rivalries and heated academic debates about the evolutionary relationships between different strains. But for now, we can rest happy in the knowledge that a crucial missing piece has been found in the account of how the pint of lager was born.

![]()

John Morrissey receives research funding from the European Union, Science Foundation Ireland and Enterprise Ireland.