An 85-year-old British citizen in Sudan was shot by snipers and his wife then died of starvation after they were left to fend for themselves by the British embassy in Sudan, their family has told BBC News Arabic.

Abdalla Sholgami lived with his 80-year-old disabled wife, Alaweya Rishwan, just over the road from the UK’s diplomatic mission in Khartoum.

But despite repeated calls for help, the London hotel owner was never offered support to leave Sudan, even when a British military team was sent to evacuate diplomatic staff. Instead, the elderly couple were told to go to an airfield 40km (25 miles) outside Khartoum – which would have meant crossing a warzone – to board an evacuation flight.

The UK foreign office acknowledged to the BBC that the Sholgamis’ case was “extremely sad” but added that “our ability to provide consular assistance is severely limited and we cannot provide in-person support within Sudan”.

Khartoum’s diplomatic area has seen intense fighting since the conflict broke out on 15 April.

The violence was triggered by a power struggle between former allies – the leaders of the regular army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

Just a few days into the conflict the family began contacting the UK embassy.

The embassy was evacuated with the support of Britain’s Army and Royal Air Force just over a week after the fighting began.

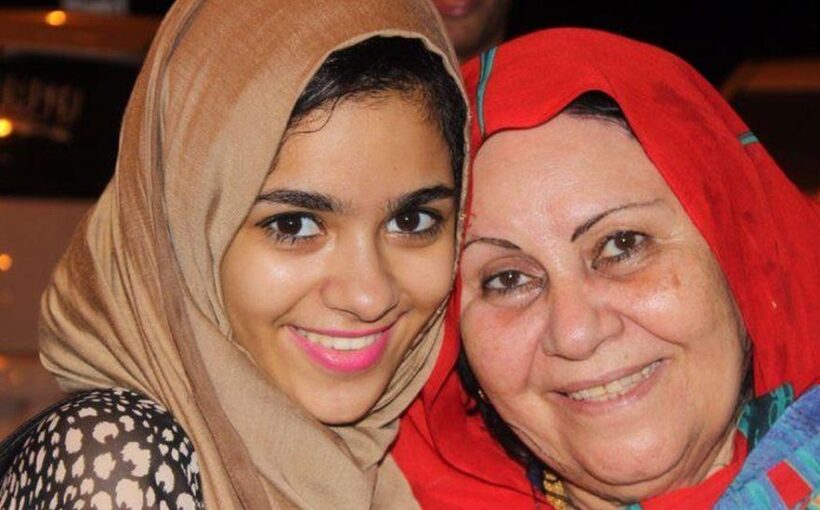

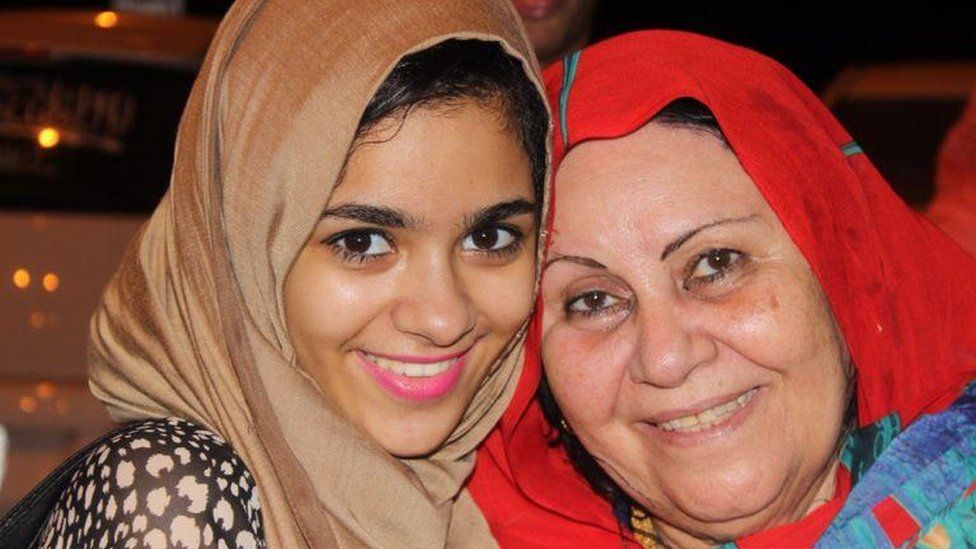

The UK embassy is a “maximum four steps away”, explained Mr Sholgami’s granddaughter, Azhaar, who grew up in Khartoum.

“I was informed they had 100 troops who came and evacuated their staff. They could not cross the road? I’m still very disappointed in them.”

Faced with starvation and with no water, Mr Sholgami was forced to leave his wife to find help. While he was out, he was shot three times – in his hand, chest and lower back – by snipers. With no hospitals working where he was, Mr Sholgami was then taken to a family member in another part of Khartoum and survived.

But his wife was now left to fend for herself and it was impossible for any family to reach her in an area that was surrounded by snipers.

The family continued to contact the UK foreign office’s hotline to help Alaweya Rishwan, but she was stuck in the house without any help and was found dead by an official from the Turkish embassy a few days later. Her body remains in the house, unburied.

The family says the UK government has done nothing to support them and have not been in touch since 3 May, which was when the last evacuation flight to the UK took off.

Azhaar Sholgami is distraught.

“What happened to my grandparents was a crime against humanity, not only by the RSF, not only by the [Sudanese army], but by the British embassy, because they were the only ones that could have prevented this from happening to my grandparents,” she told the BBC.

The UK Foreign Office told the BBC: “The ongoing military conflict means Sudan remains dangerous… the UK is taking a leading role in the diplomatic efforts to secure peace in Sudan.”

Mr Sholgami has now managed to escape to Egypt, where he is getting medical treatment after his wounds were operated on in Khartoum by his son, a doctor, without anaesthetic.

That is because only a handful of Khartoum’s 88 hospitals remain open after weeks of fighting, according to Sudan’s Doctors Union.

Hospitals have often been targeted by both sides during the conflict.

A BBC News Arabic investigation has uncovered disturbing evidence of possible war crimes being carried out on medical facilities and staff by both sides.

The BBC team used satellite data and mapping tools, analysed user-generated content on a huge scale, and spoke to dozens of doctors, to build a picture of exactly who may be committing war crimes.

Ibn Sina hospital is one of a number the BBC has identified as having been targeted in an airstrike or by artillery fire when medics were treating civilian patients.

Dr Alaa is a surgeon at the hospital and was present when the attack happened on 19 April.

“There wasn’t any warning. Ibn Sina hospital where I worked was hit by three bombs, while a fourth bomb hit the nurses’ house which was entirely set on fire,” he said.

“The duty to warn of any impending airstrike to ensure, to take due precaution, that all civilians are able to evacuate a hospital prior to an airstrike – that is very clear under the laws of war,” according to Christian de Vos, an international criminal law expert with NGO Physicians for Human Rights.

Looking at the images of the attack, forensic weapons expert Chris Cobb-Smith said it could have been caused by artillery fire.

Uncertainty over the kind of weapon used means it is hard to be sure which side was responsible, or if this was a targeted attack.

Another medical facility targeted was the East Nile hospital – one of the last operating in that part of the capital.

The BBC has seen evidence of RSF fighters surrounding it with their vehicles and anti-aircraft weapons.

There have been reports of patients being forcibly evacuated from the building. But we have also spoken to witnesses who say civilians continued to be treated alongside the RSF soldiers.

On 1 May a public area next to the East Nile hospital was hit by a Sudanese army airstrike. There was no warning, according to sources the BBC has spoken to.

Five civilians died in that attack.

There was a further airstrike two weeks later but there has been no independent confirmation of the number of injured.

The World Health Organization has reported that nine hospitals have been taken over by fighters from one side or the other.

“The preferential treatment of soldiers over civilians [is] not an appropriate use of a medical facility and it may well constitute a violation of the laws of war,” Mr De Vos said.

A political advisor to the RSF, Mostafa Mohamed Ibrahim, denied that they were preventing the treatment of civilians. He told the BBC: “Our forces are just spreading, and they are present… they are not occupying and don’t stop civilians from being treated in these hospitals.”

The Sudanese army did not provide a response to this investigation’s findings.

There is also evidence of another potential war crime – the targeting of doctors.

The BBC has seen social media messages threatening doctors by name, even sharing their ID number. The messages accuse them of supporting the RSF and receiving money from abroad.

In a widely circulated video, Major-General Tarek al-Hadi Kejab from the Sudanese army said: “The so-called central committee of doctors, should be named the committee of rebels!”

Sudanese doctors’ organisations have been monitoring threats which they say are coming from both sides and the BBC has spoken to doctors who have gone into hiding.

“We know that this is a tactic that is used in wars, for pressure, that is illegal in all international laws. Unfortunately, this has pushed medical staff into a propaganda war – between the RSF and the Sudanese army,” said Dr Mohamed Eisa from the Sudanese American Physicians Association.

Doctors around the world have been calling for an end to the targeting of their colleagues.

At a conference in London last week, Sudan’s Doctors for Human Rights said medical staff had been killed, ambulances targeted and hospitals forced to close their doors.

Dr Ahmed Abbas said: “We’re gathering all the evidence of these transgressions, which are crimes against humanity and war crimes, and this could be presented to international judicial authorities, or national authorities in Sudan.”