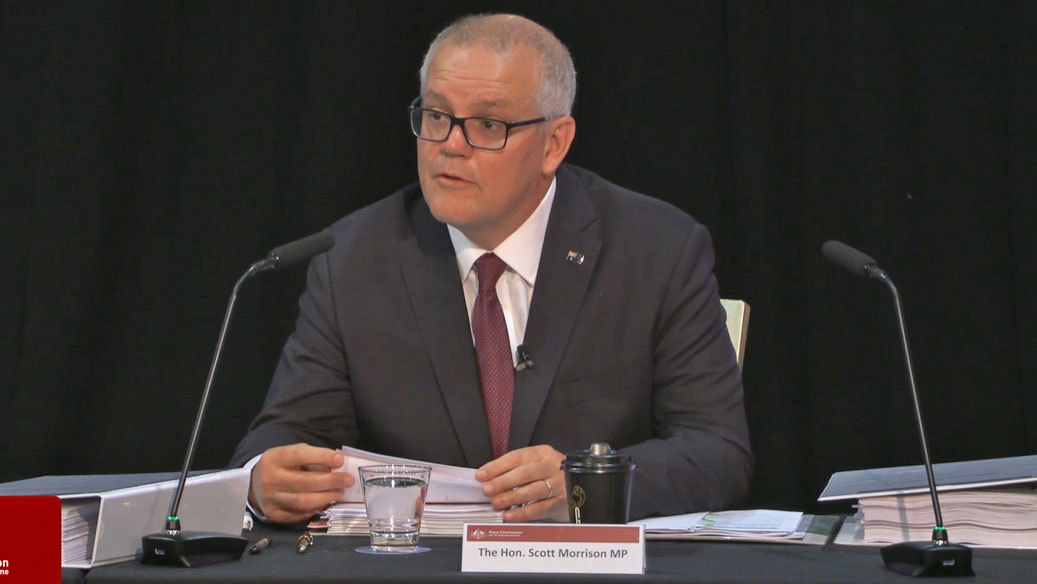

Former prime minister Scott Morrison has hit out at the robodebt royal commission’s scathing findings against him, including that he “allowed cabinet to be misled” over the scheme as a minister.

Morrison was the social services minister who brought the proposal for the debt recovery scheme to cabinet ahead of its implementation in 2015.

In a lengthy statement released a few hours after the report was handed down, Morrison furiously denied any wrongdoing.

“I reject completely each of the findings which are critical of my involvement in authorising the scheme and are adverse to me,” he wrote.

“They are wrong, unsubstantiated and contradicted by clear documentary evidence presented to the commission.

“It is unfortunate that these findings fail to acknowledge the proper functioning of government and cabinet processes in the face of not only my evidence as a former prime minister, and cabinet minister for almost nine years, but also the evidence of other cabinet ministers.”

Morrison pointed out that no findings were made in relation to his time as prime minister or treasurer, adding that he was PM when robodebt ended.

There is no suggestion Morrison is among the undisclosed persons the royal commission referred for civil or criminal legal action in a sealed section of the report.

One of the central issues of the report is the use of income averaging without additional evidence as the measure by which debts were raised and pursued.

The commission found Morrison, as a minister, received contradictory advice regarding the method of debt assessment.

The report found he “took the proposal to cabinet, knowing that it involved income averaging and that his own department had indicated that it would require legislative change, but on the basis of the contrary indication in the NPP checklist, proceeded without enquiring as to how the change had come about”.

“Mr Morrison allowed cabinet to be misled because he did not make that obvious inquiry,” the report read.

“He knew that the proposal still involved income averaging; only a few weeks previously he had been told of that caveat; nothing had changed in the proposal; and he had done nothing to ascertain why the caveat no longer applied.

“He failed to meet his ministerial responsibility to ensure that cabinet was properly informed about what the proposal actually entailed and to ensure that it was lawful.”

Morrison countered that the criticism of his actions was misinformed.

“The findings which are adverse to me are based upon a fundamental misunderstanding of how government operates,” he said.

“The commission has suggested, contrary to decisions of the High Court and long-standing practice, that a minister cannot rely upon the advice of their own department.

“Such a proposition would make executive government completely unworkable.”

Among the commission’s findings was a scathing indictment of the evidence Morrison gave regarding his knowledge of the use of income averaging.

“The commission rejects as untrue Mr Morrison’s evidence that he was told that income averaging as contemplated in the Executive Minute was an established practice and a ‘foundational way’ in which DHS (the Department of Human Services, now Services Australia) worked,” the report read.

The commission said the DHS officers who developed the proposal were unlikely to have described income averaging to Morrison as “foundational”.

Morrison claimed the finding regarding the Executive Minute was another misunderstanding.

“Regrettably the status of the Executive Minute has been mischaracterised by the royal commission, and in so doing, it is given weight it cannot bear,” he wrote.

“The Executive Minute did not have the significance which the Commission seeks to attribute to it.

“The Executive Minute did not contain settled policy proposals, it contained options to pursue the development of incomplete proposals which had yet to be subjected to the rigorous cabinet processes and departmental due diligence assessment.

“A minister would not form understandings on the legality of a measure prior to the proposal being finalised via the rigorous cabinet process and presented in a new policy proposal.

“The rigorous cabinet processes were followed and satisfied for this measure and as the minister for social services, I was constitutionally and legally entitled to assume the officers of the departments had complied with their obligations under the Public Service Act to advise their respective ministers.”

Morrison was also critiqued for his stance as a self-declared “welfare cop” as social services minister, and for using language and communicating priorities that the commission argued helped enable a favourable reception of the plan for robodebt.

The former prime minister, however, said he acted at all times in good faith.

Today, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said it was up to Morrison whether to resign or not from parliament.

“I think that these findings I’ve read out in the public domain make it clear Scott Morrison’s defence of this scheme and of the government’s actions over such a long period of time were, to quote the report, ‘based upon a falsehood’,” he said.

“That is a damning finding. People will make their own judgements about this.”