As long as a hundred of us remain alive, never will we on any conditions be subjected to the lordship of the English. It is in truth not for glory, nor riches, nor honours that we are fighting, but for freedom alone, which no honest man gives up but with life itself.

From The Declaration of Arbroath

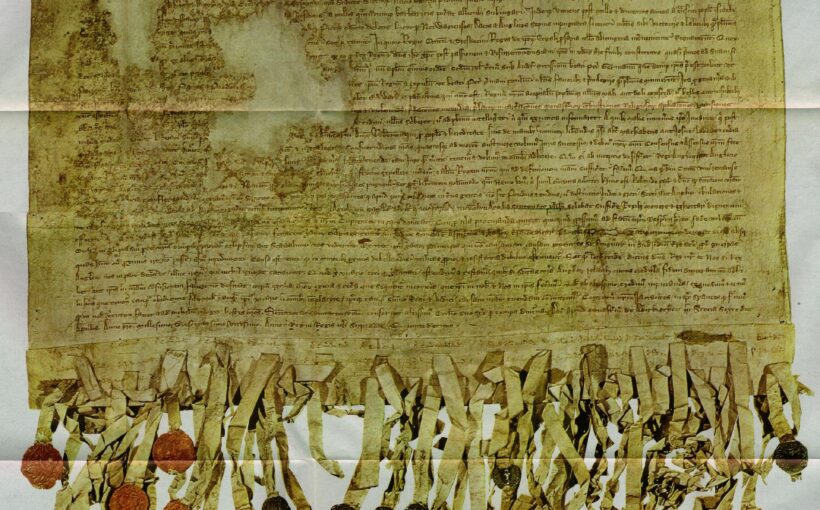

Medieval Scotland’s most iconic document, the Declaration of Arbroath, recently went on display at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh for the first time in 18 years.

The Declaration is a letter written in 1320 to Pope John XII by various Scottish aristocrats and “the whole community of the realm of Scotland”. At this time, the papacy did not recognise Robert Bruce as the true king of Scotland.

The letter was a sophisticated diplomatic response by the Scots against claims from English kings that they were the ultimate sovereigns of Scotland. The declaration is both a masterful piece of propaganda and one of the earliest statements of national sovereignty found in Europe.

It is a keystone of Scottish history, similar to Magna Carta in England which held that the English king was subject to the law of the land. The declaration has not been as widely (even comically) misunderstood as Magna Carta but it is still a contested piece of medieval history in today’s politics.

Conservative MSP Murdo Fraser claimed a few years ago that Scots who opposed independence should celebrate the Declaration of Arbroath. This is part of a tradition within Scottish unionism that sees Scotland’s victory in the wars of the early 14th century as necessary to bringing about the perfect union between the two countries in 1707.

SNP MP Joanna Cherry recently praised the document as “a statement of the sovereignty of the Scottish people”. For Cherry, this statement of popular sovereignty means the Declaration of Arbroath is incompatible with the “peculiarly English doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty”. This refers to the tradition that places parliament at the centre of English political history.

Why the declaration really matters

Both unionist and nationalist views of the declaration tell us very little about the declaration itself. They are a reminder that the past is a powerful weapon in political arguments.

We must remember that the declaration’s authors had little desire to see an Anglo-Scottish union centuries later, nor had a high opinion of popular sovereignty. Democracy too was an alien concept at this time. This was a document written for the elites, by the elites.

Indeed, there was also no concept of parliamentary sovereignty in England at this time. It was not until the 17th century that such doctrines emerged in response to the absolute political power of the Stuart kings (ironically, in this context, a family who were initially kings of Scotland).

The Declaration of Arbroath was not a law or a treaty but a letter to the pope. It had no legal weight but was a statement of political intent, and a product of political circumstances.

Robert I’s position was unstable at this time. An act of parliament in 1318 tried to control rumours that were spreading questioning his claim to be king.

When the document was written, Robert’s brother Edward had been killed in Ireland two years earlier and the king had no sons to take over if he died. His grip on power was more precarious than he realised. A few months after the declaration was sent to the pope, several individuals were executed or imprisoned for conspiracy to assassinate the king.

The declaration really gives us an insight into the development of written agreements to ensure loyalty and support. At this time, nobles across Europe, including Scotland, were beginning to write down the terms of their alliances and keep identical copies. The Declaration of Arbroath was an early example of this.

Earlier studies of the declaration concluded that nobles were encouraged to send their seals to Newbattle, just south of Edinburgh, where initial drafts were made. The final copy was drawn up at the king’s writing office in Arbroath Abbey.

The nobles may have given their seals to the document, and it may have claimed to be from the whole community of Scotland, but this was very much written for the king’s own ends.

In this respect it was the opposite of Magna Carta, in which the English king was forced to accept a document in his name forced upon him by his barons. Robert I was a king who forced his barons to accept a document in their own name.

The fact that the document was produced to serve the immediate interests of the king should not diminish its importance. The Declaration of Arbroath is a fascinating document because it tells us so much about how politics and ideas of sovereignty played out in the 14th century.

It drew on biblical and classical precedents, developing a story about the kingdom’s origins. The origin myth given in the declaration may seem like fanciful fiction today, but it resonated with the sensibilities of the time. In the 14th century, myths about history were valuable political weapons and, even though those myths have changed, they still remain powerful today.

Events of the intervening seven centuries have allowed people with opposing political ideas to call on it for their own purposes. Yet, history is too important to allow certain bits to be cherry picked for modern day purposes. It is only when considered in their immediate historical context that documents like the Declaration of Arbroath, can be understood.

The fact that there are many ways of viewing this fascinating document remind us that the historian’s job is never-ending.

![]()

Gordon McKelvie does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.