Earth is overheating due to the greenhouse gas emissions from burning fossil fuels. This is “the biggest market failure the world has seen” according to economist Nicholas Stern. The rational behaviour of companies that pollute by making profitable commodities, and consequences of most people’s desire to drive everywhere are creating irrational outcomes for everyone: an increase in the average global temperature which threatens to make the planet uninhabitable.

But our recent research indicates that this pollution will have a direct financial cost. We used artificial intelligence to combine Standard and Poor’s (S&P) credit ratings formula (which captures the ability of those who borrow money to pay it back) with climate-economic models to simulate the effects of climate change on sovereign ratings for 109 countries over the next ten, 30 and 50 years, and by the end of the century.

We found that by 2030, 59 countries will see a deterioration in their ability to pay back their debts and an increased cost of borrowing as a result of climate change. Our predictions to 2100 entail the number of countries rising to 81.

Financial markets and businesses need credible information on how climate change translates into material risks to be able to factor them into all decisions they make. Although it is important to design economic tools and policies that can mitigate the effects of climate change, the field of economics responsible for doing so is relatively young.

New financial products have emerged to help countries and investors take better account of the climate and environment being degraded as a result of debt markets, but several problems remain.

Credit ratings or environmental, social and governance (ESG) ratings (which assess how well a company manages these kinds of risks) are not based on scientific information, and are often charged with greenwashing. For example, some investment funds branded as green according to these ratings, have been linked to fossil fuel companies.

Financial institutions such as banks frequently misunderstand models for predicting the economic costs of climate change and underestimate risks such as temperature rises, according to a recent report by actuaries – people who use mathematics to measure and manage risk and uncertainty.

Their research found “a clear disconnect” between climate scientists, economists, the people building these economic models and the financial institutions using them.

In our study, we tried to integrate climate science into financial indicators widely used and understood by investors, such as credit ratings. Without such science-based indicators, financial decision making will reflect risk calculations which are incorrect and misrepresent the economic consequences of climate change.

Debt servicing to rise almost everywhere

Credit ratings express a country’s ability and willingness to pay back debt and affect the cost of borrowing to nations as well as other entities, such as corporations and banks. Inevitably, these costs are passed on to the public.

When interest rates rise for banks, businesses find it more expensive to fund their operations and so raise prices for consumers. Higher costs to banks also mean higher mortgage interest rates for residential borrowers. When banks invest savings such as pensions in bonds offered by countries hit by climate disasters, their worth is affected too, meaning that pensions may fall in value.

Our paper has three key findings. First, in contrast to much of the economics literature, we found that climate change could have material effects on economies and credit ratings as early as 2030.

Credit ratings are categorised in a 20-notch ladder scale, with default being the lowest rating, equivalent to one notch, and AAA being the highest rating at 20 notches. The highest rating signifies the lowest risk of an entity not paying back its debts and vice versa.

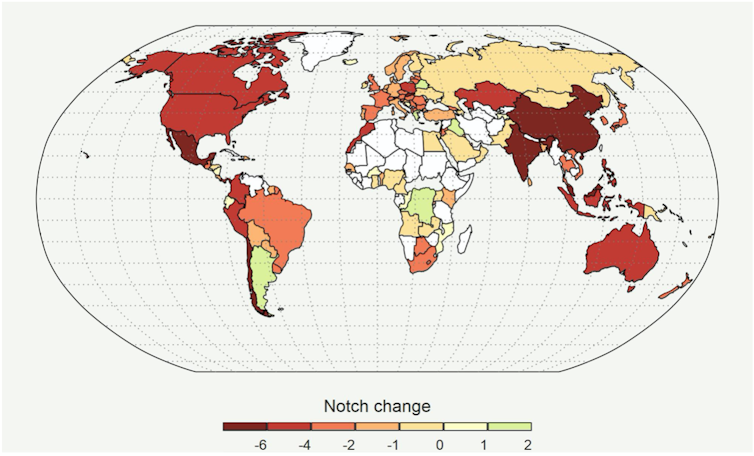

Under a high-emissions scenario in which recent emissions continue on an upwards trajectory, 59 countries would suffer downgrades of just under a notch by 2030, rising to 81 countries facing an average downgrade of two notches by 2100.

The nations which would be most affected include Canada, Chile, China, India, Malaysia, Mexico, Slovakia and the US. More importantly, our results show that virtually all countries, whether rich or poor, hot or cold, will suffer downgrades if the current trajectory of carbon emissions is maintained.

Second, if countries honoured the Paris Agreement and limited warming to below 2°C, the impact on ratings would be minimal.

Third, we calculated the additional costs of servicing debt for countries (best interpreted as increases in annual interest payments) to be between US$45–67 billion (£35-53 billion) under a low-emissions scenario, and US$135–203 billion under a high-emissions one. These translate to additional annual costs of servicing corporate debt, ranging from US$9.9–17.3 billion to US$35–61 billion in each case.

As climate change batters national economies, debt will become harder and more expensive to service. By connecting climate science with indicators that are already baked into the financial system, we’ve shown that climate risk can be assessed without compromising the integrity of scientific assessments, the economic validity of the modelling and the timeliness necessary for making effective policies.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Patrycja Klusak receives funding from the International Network for Sustainable Financial Policy Insights, Research and Exchange (INSPIRE).

Matt Burke receives funding from the International Network for Sustainable Financial Policy Insights, Research and Exchange (INSPIRE).