Like many conscientious objectors during the second world war, John Corsellis was acutely aware of the complex and conflicted position he was taking. Years later, he told the Imperial War Museum’s oral history project:

I was always pretty strongly conscious of the illogicality of the pacifist position … I was well aware of the very great and extreme evil of Nazism, and conscious that the pacifist had only a very thin answer indeed as to how Nazism could be opposed in any other way than by force of arms.

Corsellis, the son of a barrister and educated at Westminster School in London, was far from alone in this inner-conflict. According to my research into these conscientious objectors – who remain far less well understood than their first world war counterparts – many were plagued with feelings of doubt, finding it difficult even years later to express their reasoning.

Corsellis was one of some 60,000 British men and 900 women who attested a conscientious objection during the second world war. (Many more women would like to have declared themselves conscientious objectors, but had no official way of doing so.) The 1% of conscripted men was proportionally more than the 16,000 who objected in the two years of conscription during the first world war. Most, but not all, objected on religious grounds and were from middle- or upper-class backgrounds. Most, but not all, were still willing to work in some capacity for Britain’s second world war effort.

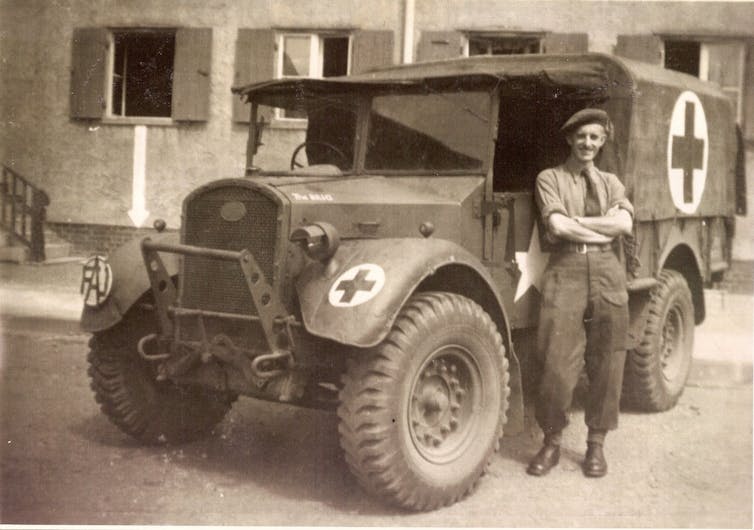

Indeed, this new breed of “conchie” often displayed a strong desire to relieve the suffering of war – and were willing to risk their lives far from home. Having initially worked with the Quaker-affiliated Friends Ambulance Unit at home, Corsellis was sent to the El-Shatt refugee camp in Egypt and later the UN Relief and Rehabilitation Administration in Italy and Austria. There he witnessed the forced repatriation of refugees to eastern European countries including Yugoslavia – where many faced summary execution. (The trauma of these experiences led to Corsellis spending the rest of his life raising awareness of the fates of Yugoslav displaced persons.)

A colleague on these missions, A. Tegla Davies, later described the motivation of second world war objectors in his history of the Friends Ambulance Unit:

When the war came upon them, the state treated them with surprising leniency. Some members of the unit went to prison, but for the majority the battle of the prisons had been won by the steadfastness of their [objector] fathers in the previous war. Now they felt that pacifism, having been recognised by the state, should show in action what it could do to relieve the suffering and agony which years of war were bound to produce.

‘The pacifist is not a freak’

Where first world war objectors can be characterised by their persistent opposition to the state, objectors in the second world war were generally willing to compromise so as to be useful in a non-combatant way. Despite being pacifists, they could be found in every corner of the war – and their experiences were often not so different from their fighting contemporaries. As Davies wrote:

The normal, healthy young pacifist is not a freak. He feels the same passions and emotions as his fellow men. He does not enjoy being classed as odd or different. When war comes he is in a dilemma. If he joins the army, he violates his deepest convictions. If he refuses, he is in danger of cutting himself off from the community. Some are not unduly worried by that segregation. Others are tortured by it.

Feelings of doubt were common among second world war objectors. Faced with a much more tolerant and flexible governmental strategy than the punitive stance of the first world war, ironically this engendered a much less certain course of action in many.

Even before the truth about Nazi atrocities came to light, their war was also a much more obvious battle between good and evil. The author and broadcaster Edward Blishen was working in Barnet as a young journalist when war was declared. Turning 18 in 1940, he was required to register as a conscientious objector just as France fell to the Nazis – a coincidence of events that tortured him, according to his war memoirs:

The shock of knowing that France was finished, and the voice within you saying: ‘You can’t … You can’t not be in it now – not now they’ve done this to France.’

Yet despite this “voice of disloyal temptation”, Blishen registered as an objector, later recalling:

I was sent to the bottom of the buzzing room, alone, away from all the others; and it felt as though I was separating myself from the world.

At his June 1940 tribunal, Blishen was granted agricultural work. Unlike in the first world war, these tribunals were headed by a civilian judge and included representation from trade unions. Incarceration was rare, with only 3% of men – compared with one-third in the first world war – given a prison sentence (generally 3-6 months) as a result of refusing to engage with the process of the tribunal altogether.

Complete exemption from military service was also rare. Around three-quarters of those applying for CO status were directed to work of “national importance”. This ranged from agricultural work to service in the army – either in the medical services or the specially formed Non-Combatant Corps.

Blishen’s doubts persisted throughout the war. He didn’t enlist, but was painfully honest about the “feeling of shame” that haunted him as the fighting finally came to an end:

I wondered, had I been motivated simply by the dread of being killed or maimed? … Wasn’t it true that through five years of universal agony, I had hidden away in despicable refuge? Had I even been a good pacifist? I had shuffled, hummed and hawed – put off all painful decisions. There it was, nearly over, and I was ashamed of myself.

‘We needed each other’

As in the first world war, nearly all who claimed objection at tribunal did so on the grounds of their religion – with many coming from traditionally pacifist churches such as the Quakers.

The Friends Ambulance Unit (FAU) in which Corsellis and Davies served was a re-creation of a first world war service that treated both military and civilian casualties. Predominantly funded by the Cadbury family of Quakers famous for its chocolate bars, the unit engendered a sense of solidarity among objectors according to another member, William Brough:

We needed each other. We needed the confirmation of each other. We needed the affirmation of each other.

Within the unit, the legacy of the first world war loomed large. Corsellis, whose father had lost an arm during the infamous Gallipoli campaign, said he grew up strongly conscious of the “great war”, and argued that his entire generation felt the same. Avoiding a repeat of its destruction was, he added, a “major factor” in his pacifism. Fellow FAU member Michael Cadbury (a distant relative of the chocolate-making family) noted that he and his contemporaries were operating “on top of the mountain” that their forefathers “had scaled on our behalf”.

The popularity of great war poets during the objectors’ formative years was another important factor for some, including Blishen:

I looked at things very simply in those days. Pacifism had seemed to be the air we all breathed when we were in the grammar school together … We all read Remarque and Barbusse and Toller, and our views had always appeared so beautifully clear. War was black. Any war was black.

The horrors of the western front trenches are persistent motifs in the writings and interviews of many second world war objectors. For example, Mark Holloway described in a collective memoir how:

All through childhood, real and imaginary pictures of the war flickered semi-consciously in front of me like Very lights. They were supplemented later by visits to Belgium – where my parents proudly showed me Zeebrugge and described its intricate wartime history – and to the battlefields with their actual soundbites, trenches, barbed wire and charred stumps of tree that people still pay to see 10 years after war ended.

‘Ought I to rethink this?’

Conscientious objectors weren’t all united in their reactions to the onset of the second world war. While many were willing to work alongside and even in the military, others took a very different position.

Tony Parker grew up in Manchester, the son of a cotton merchant who also owned a second-hand bookshop. This shop, where Parker had worked while at school, was a gateway to pacifism for him. The prominent anti-war literature he read there, notably the poems of Siegfried Sassoon – author of The Dug-Out and Suicide in The Trenches – made him realise that war was “nonsensical”.

At his initial tribunal in 1941, Parker was granted non-combatant or ambulance service, but he appealed this and was given mining work instead. Unlike the camaraderie engendered by units like the FAU, Parker was not part of any pacifist group and was the only objector sent to his mine, Bradford Colliery in Manchester. Of this time, Parker recalled:

I think you did feel very alone – or at least, I did … All the time one was saying: ‘Am I doing right or am I doing wrong. Ought I to rethink this?’

In the mine, Parker described himself as “like a strange being from another world” due to his markedly middle-class accent and upbringing. But though short-lived, it proved a transformative moment in his life. “I had never thought there was this kind of life that people had,” he recalled, adding that a friendship with another young miner – with whom he swapped poetry and classical records – had “stopped me thinking there was anything special about a middle-class education”.

Parker’s experience in the mine fuelled his socialism and politicised him in a way which would have been unthinkable before the war, as he learned about “working life in terms of not having things”. After suffering a broken arm and ribs while uncoupling two wagons of coal, he returned to work in his father’s bookshop – but the legacy of this time as a miner is clear. Parker spent the rest of his working life as a pioneering oral historian, interviewing people “marginalised” by and living on the outskirts of society – including criminals, lighthouse keepers and single mothers.

‘I had to join the damned’

Upon the outbreak of the second world war, Patrick Kenneth Mayhew joined the Royal Army Medical Corp (RAMC) of the British Army and was deployed for service in France – where he became embroiled in one of the most infamous events of the war.

Once the German army invaded France on May 10 1940, Mayhew found himself part of the British army’s immediate retreat. His unit set up a field hospital in a hotel in the town of De Panne, on the Belgian-French border about ten miles from Dunkirk. They worked tirelessly on the many wounded until, in Mayhew’s words: “We were becoming the front instead of the back.”

It was decided that an aid party comprising just one officer and four lower-ranked men would stay to help those who could not be evacuated. Despite not feeling “brave or proud”, Mayhew volunteered and spent 24 hours alternating between medical work and collecting identification disks from the dead outside.

Eventually, his aid party was instructed to evacuate. They made their way to the beach at De Panne, boarded a boat, and rowed for nine hours until they reached the shores of Margate. For his service, Mayhew was awarded the Military Medal for “bravery on land” – despite his strictly non-combatant status.

The awarding of war medals to conscientious objectors was a rarity. Other recipients include members of the FAU’s Hadfield Spears ambulance unit, who received France’s Croix de Guerre, and Desmond Doss, an American pacifist medic who became the first objector to receive the Medal of Honor (the US Armed Forces’ highest military decoration) for going “above and beyond the call of duty” during the Battle of Okinawa, Japan, in 1945. Doss, who refused to carry a weapon of any kind, was the subject of the 2016 Hollywood biopic Hacksaw Ridge.

In Mayhew’s case, the award caused quite a stir. His brother Paul thought it hilarious that a pacifist should win a medal for military bravery and the British press agreed, with several newspapers running articles on Mayhew. But these articles also delighted in the fact that he changed his mind – in the summer of 1940, Mayhew joined the combatant services of the army.

While it was tempting to see a straight line between his harrowing experiences in Dunkirk and this change of heart, Mayhew vehemently rejected this, recalling years later:

It wasn’t anything of the sort. I saw nothing which made me change my mind in that way. Nor – and this is where it becomes so inconsistent – did I feel that I’d been wrong in my Christian belief that war is not acceptable.

Instead, Mayhew blamed the intensity of the war in the summer of 1940, when invasion of Britain by the Nazis looked certain:

You weren’t taking time to think and read books and make up your mind, and talk to this person and that person, and let the thrill of Dunkirk die off … These were immediate, imperative decisions. I found so much in this country that I wanted to do or that I believed in … And I hated the idea of that going down the drain.

Mayhew added that it would have been very easy for him to stay in the RAMC – and that no one would have questioned his pacifism. In his own fascinating description, he was “the right sort of pacifist”: because he was willing to risk his life and help the war effort, his stance was acceptable to the wider public.

But Mayhew’s family was another key driver in his change of heart. The son of Lord Basil Mayhew, his elder siblings were scattered across the world doing “war work”, and he decided he didn’t want to “save his own soul” while his family committed “mortal sins”. Instead, “I had to join the damned.”

Mayhew was far from the only objector to renounce their status and join the military during the second world war. Another was the poet Timothy Corsellis – John’s younger brother – a pacifist who joined the RAF but refused to serve with Bomber Command as he did not want to participate in the indiscriminate bombing of civilians. In 1941, during his service with the Fleet Air Arm, his plane stalled during a training flight and he crashed and died near Annan in south-west Scotland.

‘A turmoil of doubts’

Summing up the second generation of world war objectors is a difficult task. Where their first world war counterparts have become simplified in popular representations, with their valiant opposition to a war that is almost universally condemned, the COs that followed two decades later appear as more nuanced, conflicted human beings.

They doubted their stances. They worried about their families. They felt torn between their duties to society and their duties to themselves and their beliefs. They keenly knew the horrors of the first world war, but they also felt the threat against their country and the emerging horrors of Nazism. Theirs was a complicated position.

The English poet and folk musician Sydney Carter was born in London to a military father. Although from a working-class background, he received a bursary to Christ’s Hospital private school before going to Oxford to read history at Balliol College. While his pacifism was ostensibly based on his religious beliefs, his decision to object was driven as much by heartbreak as anti-war sentiment. He recalled later in an interview for the Imperial War Museum archive that:

Pacifism seemed to offer something like a religion I could live by. It exposed inside, like a light: and suddenly, I felt quite free … It was as inexplicable as my religious experience had been at Christ’s Hospital; I clung to it through the dark years of the war, as [close] to a divine command that I ever had.

At his tribunal, Carter was granted service with the FAU, although he doubted “right up to the last moment and after it”. He admitted to having “a lot of non-pacifist things inside me”, and said he had joined the ambulance unit because it promised to be “arduous and dangerous”.

He was right. After doing perilous shelter work in Britain at the height of the Blitz, he was later posted to Egypt and Palestine. While serving at Nuseirat, a camp for Greek refugees, he took the decision “to cast myself into the melting pot, join the Army, [then] see what shape I came out – if I ever did”.

Carter informed his camp commander and set off for Cairo to enlist. Before he reached the Egyptian capital, however, he changed his mind again, and decided to “stick with the people I know”. This turmoil of doubts persisted throughout the war and after. In his 1965 memoir The Objectors, he wrote:

Once, I was a conchie. Why? For over 20 years I have been trying to find out. I could name some noble reasons but, even at the time, I am sure that there were tares among the wheat. Had I gone into the Army, no one would have questioned whether my motives were sincere or not. But being a conchie, I had to justify them – not only to the Tribunal, but to myself. I managed to convince the Tribunal. I’m not sure I ever managed to convince myself.

![]()

Linsey Robb receives funding from the AHRC (Arts and Humanities Research Council).