After the assassination of Ecuadorean presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio in Quito on August 9, former president Rafael Correa posted a message on his social media feed: “Ecuador has become a failed state.” It was a stark message as the country prepares to go to the polls on Sunday August 20.

Villavicencio’s shooting followed the murder on July 23 of Agustín Intriago, the mayor of the port city of Manta, and that of Rider Sánchez, who was running for a seat in the national assembly when he was shot dead on July 17 while campaigning in the northern coastal province of Esmeraldas.

Sunday’s parliamentary and presidential election are being held as a result of outgoing president Guillermo Lasso dissolving parliament in May. Lasso faced impeachment by opposition parties over allegations of connections to corrupt government contracts, something he and his supporters vehemently deny. Villavicencio campaigned on a pro-security and anti-corruption platform and, while not considered a frontrunner, his assassination deeply shocked the nation.

Island of peace?

Sitting between Colombia to the north and Peru to the south, two of the world’s largest producers of cocaine, Ecuador was until recently known as an “island of peace” in this war-torn region.

This had a great deal to do with the success of Correa’s policy while president from 2007-2017 of effectively legalising gangs as “cultural associations” or urban youth groups. This allowed them to apply for government funding and grants in return for a pledge to end violence.

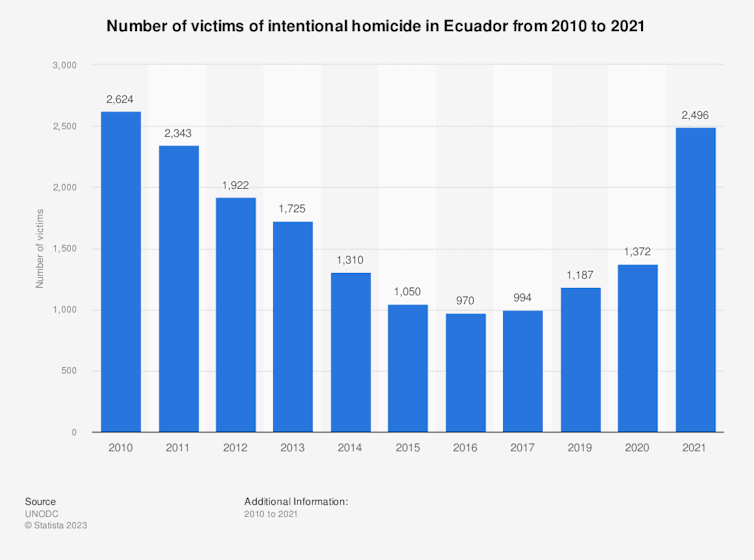

Correa’s policy saw the country’s homicide rate fall sharply. In the past five years, however, the murder rate has begun to increase sharply again, making Ecuador one of the region’s most violent countries.

Villaviciencio had already made plenty of enemies when he took up politics, having exposed multiple cases of corruption during his time as a journalist. In January, while still a member of the national assembly before its dissolution, Villavicencio denounced 21 mayoral candidates for alleged links to drug trafficking. He also revealed he’d received death threats from Los Choneros, one of Ecuador’s most powerful “mega-gangs”, involved in illegal activities ranging from narco-trafficking to contract killings and extortion.

Villavicencio’s killer was shot by security forces in the immediate aftermath of the attack, and six further suspects have been detained. They are all of Colombian origin and reportedly members of criminal groups. After decades of armed conflict, Colombia has a reputation for producing and exporting contract killers. Both Haiti’s former president, Jovenel Moïse, and Paraguayan anti-corruption prosecutor Marcelo Pecci were assassinated by Colombian mercenaries.

Culture of violence

As recently as 2018, Ecuador had one of the lowest annual homicide rates in Latin America, at 5.7 people per 100,000. This compared favourably with neighbouring Colombia at 25 people per 100,000, Brazil at 27.6 and Venezuela at 81.4 – a rate which has since fallen to the (still-calamitous) level of 40 murders per 100,000 people.

But following a recent sharp rise in drug trafficking and gang violence, Ecuador is now one of the region’s four most violent countries. The latest data shows the homicide rate increasing to 22 people per 100,000 in 2022 – above the average of 20 per 100,000 for Latin America (but still below that of Colombia at 27 per 100,000).

Much of this violence is directed from the country’s jails, which are now virtually controlled by criminal gangs. Despite being incarcerated, gang leaders control a wide range of criminal activities – including networks which move cocaine from Colombia and Peru through Ecuador’s massive ports into major drug markets in Europe and the US.

Ecuador itself isn’t a major drug-producer and, unlike Colombia, has no history of guerilla or paramilitary activity. Yet, in the past 15 years, the country developed into a major logistical hub for international criminal organisations. In an interview with BBC Mundo in 2019, Ecuador’s former director of military intelligence, Colonel Mario Pazmiño, estimated that 40% of Colombia’s cocaine production transited via Ecuador – and data on seizures and raids on processing labs suggests Ecuador’s role as a transit hub has increased further since then.

Colombia’s 2016 peace agreement and the resulting dismantling of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) was a turning point. Until then, Farc controlled drug trafficking routes from southern Colombia to Ecuadorean ports. Its dismantling led to the creation of dissident groups in Colombia, and opened the door to Mexican criminal organisations attempting to gain control of Farc routes.

According to the UN’s 2023 Global Report on Cocaine, the Cártel de Sinaloa and Cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación “largely control the trafficking corridors between Mexico and the US” and are fighting for supremacy. Villaviciencio had campaigned on the growth of this drug trafficking and explicitly named the organisations involved, for which he was murdered.

Bleak outlook

The outlook for Ecuador isn’t promising. Global demand for cocaine continues to increase and production in Colombia is at a record high. The UN estimates that one-third of Colombia’s illicit coca fields are located within 10km of its frontier with Ecuador.

This can only mean that Ecuador’s role in the drug supply chains continues to grow in importance, especially as peace efforts in Colombia continue. Venezuela, through which 24% of global cocaine production transits, has a similar problem

After three days of mourning for Villavicencio, campaigning has resumed ahead of the election on August 20. Opinions polls show that security is by far the biggest concern for voters, and all candidates are campaigning on the issue – understandable in the wake of Villavicencio’s murder. But in a country where 87% of people don’t trust democracy itself, the outlook is gloomy, to say the least.

![]()

Nicolas Forsans does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.