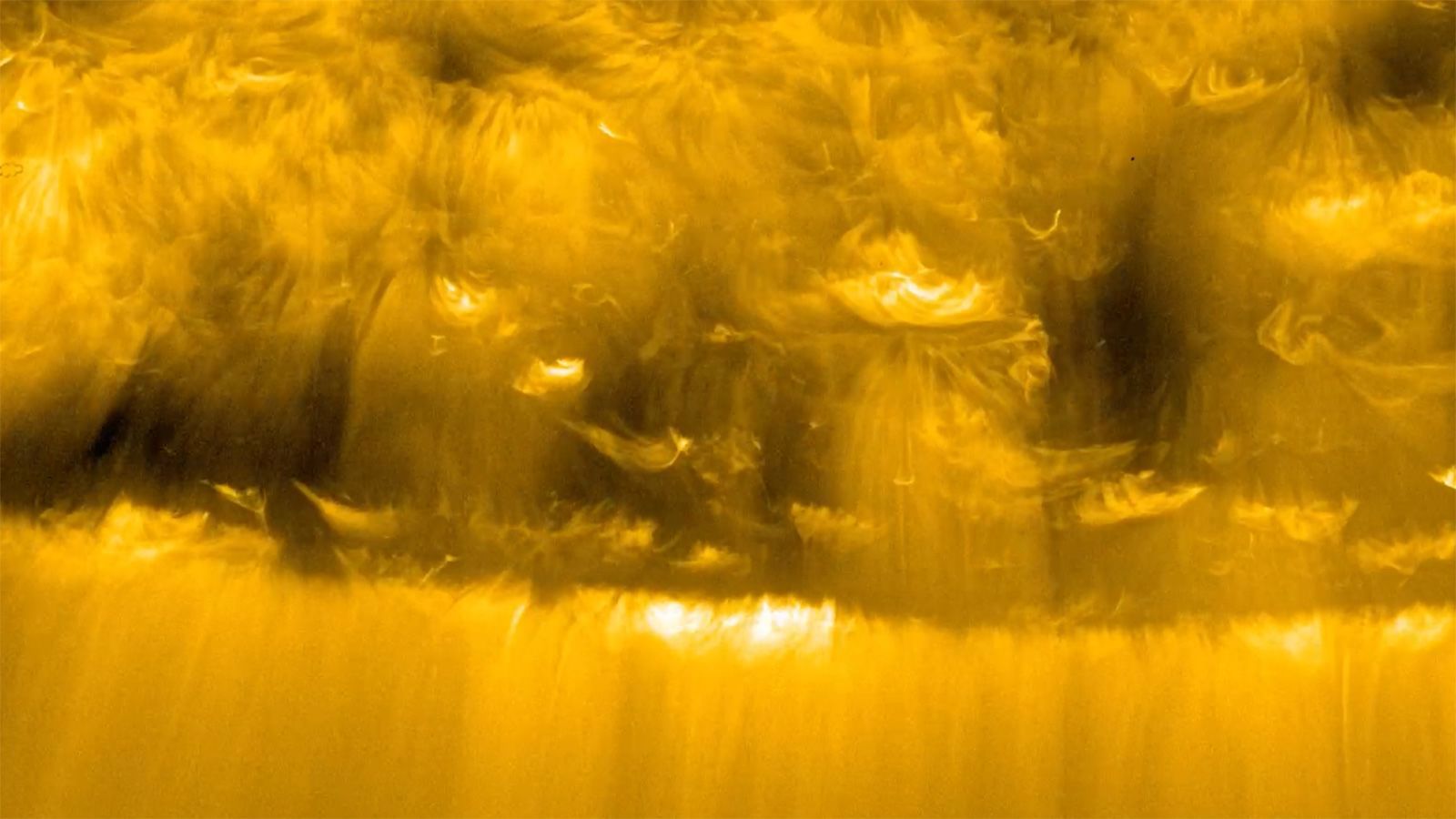

The Solar Orbiter mission has discovered jets of material rapidly releasing from the sun’s outer atmosphere.

Astronomers believe these jets could be the source of the solar wind, a stream of charged particles that continuously flows from the sun across the solar system.

The jets of charged particles, called plasma, last between 20 and 100 seconds each and move at about 360,000 kilometres per hour.

Solar Orbiter, a joint mission between NASA and the European Space Agency, launched in 2020 to capture an unprecedented look at the sun by providing images of its north and south poles.

Having a visual understanding of the sun’s poles is important because it can provide more insight about the star’s powerful magnetic field and how it affects Earth.

The spacecraft is equipped with 10 instruments that can capture observations of the sun’s corona (or superhot outer atmosphere), the poles and the solar disk.

The probe can also measure the sun’s magnetic fields and solar wind.

Solar Orbiter’s Extreme Ultraviolet Imager, or EUI, was used to take images of the sun’s south pole in March 2022.

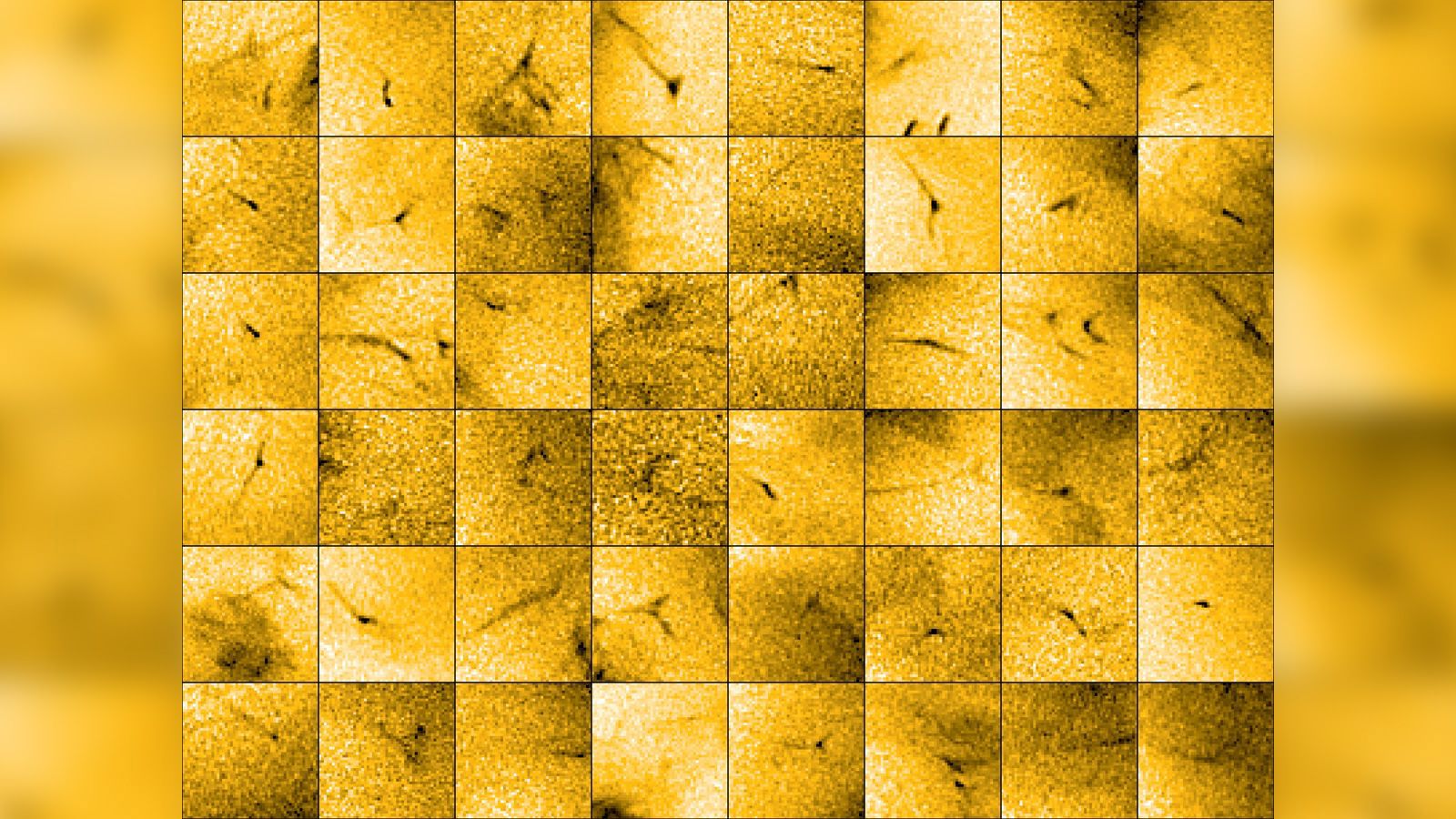

The images, released along with a new study published Thursday in the journal Science, show the faint, ephemeral jets, some of which are shaped like the letter Y.

“We could only detect these tiny jets because of the unprecedented high-resolution, high-cadence images produced by EUI,” said lead study author Lakshmi Pradeep Chitta, a research group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany, in a statement.

Astronomers have known about the existence of the solar wind for decades.

But understanding the exact nature of how and where it is created by the sun has been more difficult – until now.

The advanced instruments aboard Solar Orbiter, as well as NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, are helping to unlock the biggest mysteries that remain about the sun.

How the sun affects activity on Earth

Understanding the sun’s magnetic field and solar wind is key because they contribute to space weather, which affects Earth by interfering with networked systems such as GPS, telecommunications, and the operations of objects in low-Earth orbit such as satellites and the International Space Station.

When the solar wind collides with Earth’s magnetic field, it can also create colorful auroras, such as the northern and southern lights.

Previous observations have helped astronomers to determine that part of the solar wind stems from magnetic structures on the sun called coronal holes.

These features are regions where the magnetic field extends outward, rather than turning back into the sun.

The sun’s magnetic field is so massive that it stretches beyond Pluto, providing a pathway for solar wind to travel directly across the solar system.

But the remaining question that scientists have been puzzling over was how the charged particles were released in the first place.

Solar Orbiter’s observations captured a coronal hole containing tiny individual jets at the south pole.

Each jet is releasing a small amount of plasma, which suggests that the solar wind is less of a continuous flow than previously believed.

Energy flow from coronal holes

The new results show that the particles are being expelled from the sun’s atmosphere.

Solar Orbiter’s observations captured a coronal hole containing tiny individual jets at the south pole.

Each jet is releasing a small amount of plasma, which suggests that the solar wind is less of a continuous flow than previously believed.

“One of the results here is that to a large extent, this flow is not actually uniform,” said study coauthor Andrei Zhukov, senior research scientist at the Royal Observatory of Belgium, in a statement, adding that “the ubiquity of the jets suggests that the solar wind from coronal holes might originate as a highly intermittent outflow.”

Solar Orbiter is on a seven-year mission and will eventually come within 42 million kilometres of the sun.

Currently, the spacecraft is closer to the sun’s equator, and it will gradually shift toward the poles.

“It’s harder to measure some of the properties of these tiny jets when seeing them edge-on,” said ESA’s Daniel Müller, project scientist for Solar Orbiter, in a statement, “but in a few years, we will see them from a different perspective than any other telescopes or observatories so that together should help a lot”.

Solar Orbiter’s position will incline as the sun’s activity increases and nears the peak of its 11-year cycle, which means more coronal holes and jets may appear in different places for the spacecraft to observe.

Solar Orbiter works in tandem with Parker Solar Probe, which is orbiting the sun on a seven-year mission after launching in August 2018.

Parker will eventually come within nearly 6.4 million kilometres of the sun – the closest a spacecraft has ever flown by our star.

The probe is “tracing the flow of energy that heats and accelerates the sun’s corona and solar wind,” according to NASA.

Together, the missions can provide more data to researchers than either could accomplish on its own.

Parker can sample particles coming off the sun up close, while Solar Orbiter will fly farther back to capture more encompassing observations and provide broader context.