UK prime minister Rishi Sunak appears to be wavering on “net zero by 2050” that Theresa May successfully passed through parliament with barely a cough of disapproval in 2019.

Sunak is now talking about more “proportionate and pragmatic” government climate policies, while also announcing plans to issue at least 100 licenses for new oil and gas projects in the North Sea.

This shift comes at a time when British holidaymakers are fleeing wildfires in Rhodes and Corfu, and so many climate records are tumbling that it’s hard to keep up.

The Conservative Environment Network, an independent forum for conservatives who support net zero, and others including Greenpeace, are trying to stiffen his spine. But Sunak appears minded to appease those on the “right” who are opposed to anything green.

This stance might seem surprising. But taking a global and historical perspective provides some context to the situation.

The UK story

The UK’s modern environment movement can be dated back to 1969 when the then prime minister, Harold Wilson, gave the first ever speech to a party congress that mentioned “the environment”. Visiting the US the following year, Wilson proposed a new special relationship based on environmental protection.

Far from decrying this, Conservative opposition leader Edward Heath accused Wilson of being too slow. When Heath became prime minister in 1970, he created a huge Department of the Environment.

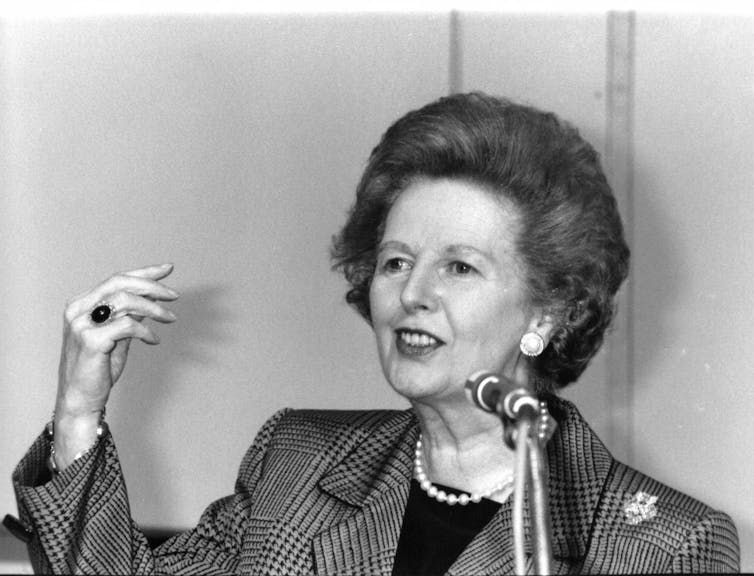

While “the environment” faded from the headlines thanks to the oil price spike of 1973, high inflation and other issues, neither the Tories nor Labour backtracked. In 1979, new prime minister Margaret Thatcher even mentioned the greenhouse effect while in Tokyo for a G7 meeting.

However, Thatcher took an obstructive line on acid rain. This was something Sweden was especially exercised about, since sulphur from British coal stations was altering its lakes and rivers.

It was only in 1988, after persistent lobbying from scientists and diplomats that the lady was for turning. Her speech to the Royal Society (a fellowship of eminent scientists) about the “experiment” humanity was conducting in tipping so much carbon dioxide into the atmosphere is regarded as the starting point for modern climate politics.

Thanks to switching from coal to gas in the 1990s, and moving industry offshore, the UK could for a long-time boast of reducing its emissions and speak nobly of sustainable development. In 1997, Tony Blair said the UK would go further in cutting emissions than whatever target was set at the UN conference in Kyoto, the first agreement by rich nations to cut greenhouse gases. This was met with few grumbles from the Tories.

In the late 2000s there was a fierce “competitive consensus” (where politicians try to outbid the their competitor’s bid for votes and virtue) around passing a Climate Change Act. The then new Conservative leader, David Cameron, had taken a trip to the Arctic and was now saying “can we have the bill please”.

Very few Conservative MPs voted against the 2008 Climate Change Act, which set an 80% reduction in emissions by 2050 and placed restrictions on the amount of greenhouse gases the UK could emit over five-year periods.

Once in power, Cameron supported fracking, opposed onshore wind, and scrapped climate policies in a self-defeating effort to reduce costs (allegedly ordering aides to “get rid of all the green crap”). But he did not, at least not directly, attack the Climate Change Act.

After the Paris agreement in 2015, which the UK signed, it became clear that 80% would not be enough of a target to have the UK meet its obligations to do its part to keep global warming under 2℃. And pressure built for a net zero emissions by 2050 target. This was one of Theresa May’s final acts, and was enthusiastically endorsed by all parties.

So what’s gone wrong?

Politicians tend to like targets that are distant, round numbers like 2050. They get the glow, without the pain of upsetting either vested interests or demanding that ordinary people change their behaviour. What we are seeing now, I believe, is a collision between what the promises were and what the immediate action has to be.

This is not unique to the UK. There have been periods, albeit brief, of bipartisan consensus around environmental issues in both Australia and the US.

But once in power, Conservative governments have tended to prioritise “free markets” over what they label as irksome or socialistic environmental regulation. The main motor of climate denial, and framing green concerns as like a “watermelon” (green on the outside, red on the inside) has historically been the United States.

One way of looking at what is happening in the UK Conservative Party now is that the same imported “culture war” tropes that gave the UK an unevidenced “voter registration” panic in May 2023, is now turning to climate policy. This phenomenon is what was behind the recent Just Stop Oil action at Policy Exchange, a right-wing think tank that helped draft controversial new laws cracking down on climate protesters.

The recent Uxbridge by-election result, where the Conservatives’ narrow victory was driven by anger against London’s ultra-low emissions zone (an area where drivers of the highest-polluting vehicles must pay a fee), is likely to have whetted the appetite of right-wing Tory strategists.

They may see this as a way of dividing Labour and either winning the next election by weaponising climate policy, or at the very least, reducing their losses to “manageable proportions”.

Meanwhile, the emissions climb, the ice melts and the waters warm. And everyone will be holding their breath for every food harvest from here onwards.

![]()

Until January 2023, Marc Hudson was a research fellow on a project investigating the politics of industrial decarbonisation, funded by the Industrial Decarbonisation Research and Innovation Centre