It started with odd gardening jobs during university, but now 25-year-old Conor McGreevy has grown his business to include nine staff, four utes and a removal truck.

“It was a bit of a dream being able to run my own business,” Conor McGreevy said.

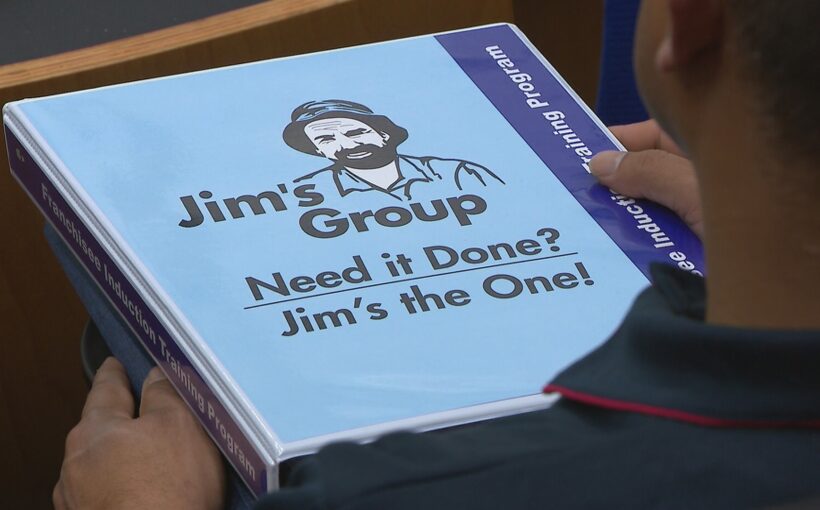

He bought into Jim’s Mowing in 2020, and says the brand recognition and training the franchise provides has helped him grow his customer base.

“The marketing they provide gives us enough leads, enough work to actually grow it,” McGreevy said.

Franchising is a $170 billion dollar industry in Australia, and when it works well, it gives people the chance to become their own boss and run a lucrative business.

But when it goes wrong, franchisees are trapped running bad or unprofitable businesses, with no way out of expensive and complex contracts.

Jim’s Mowing founder Jim Penman has serious concerns about the sector, saying regulations protect big business, not hard-working franchisees.

“What goes on is an incredible rip-off game across the country, so many franchisors act unfairly,” said Penman.

“The law as it is stands fully behind the franchisor, and does stuff all for the franchisees.”

Penman has made submissions to the independent review, commissioned by the Treasury, currently underway into the Franchising Code of Conduct.

“The code is pathetic. The code is weak as water. Worthless, nothing,” Penman said.

One business owner who knows the dangers first-hand is Laziz Mirdjonov, who opened a UFC Australia gym in Castle Hill.

“I thought it would be quite an honest and high-integrity company,” said Mirdjonov. “It was pretty much my lifetime investment going through the bin.”

He sunk millions into the business, including on set-up costs and fees which were not disclosed upfront.

“They’re like a spider that’s sucking blood out of you and they’ve got all the power,” said Mirdjonov. “You’re still paying your fees through the whole thing and to get out of the franchise you’re going to lose everything.”

Mirdjonov teamed up with two other UFC Gym Australia franchisees to take the franchisor to court.

“At the time I was quite naive about the franchising code, but later I realised that the franchising code is just a bunch of rules that doesn’t apply to the franchisor until you take them to court,” said Mirdjonov.

“We went through the litigation, it took us a good four years and a million out of pocket, not including any expenses we had for the business to run.”

The Federal Court ruled in their favour in May, ordering the parent companies of UFC Gym Australia pay more than $5 million to the three franchisees.

But a day later, the parent companies went into voluntary administration.

“Even though we got the result, we still haven’t seen the money,” said Mirdjonov.

Regardless, he’s still pushing on with his business under a new name “Rival”.

“We’re just going to continue growing and growing and opening more clubs,” said Mirdjonov.

The public is being encouraged to have their say in the franchising review by September 29, either by phone, email or mail, and submissions can remain anonymous.

But some experts think reform should go much further than tweaking the code of conduct.

“The franchise code is just one part of the picture,” said Professor Jenny Buchan, a UNSW Franchise Law Expert. “They should be regulated by stand-alone legislation.”

Information on the Review of the Franchising Code of Conduct is located on the Treasury website.