From the beginning, Russia has framed its invasion of Ukraine as necessary for the defence of the country. According to Vladimir Putin, Nato’s deliberate and aggressive encroachment into a region once dominated by Moscow is to blame, as the west seeks to dismember Russia. By extension, Ukraine – a country, according to Putin, without agency and turned into a Nato military outpost – is little more than a pawn in Washington’s nefarious game.

Some conspiracies in Russian propaganda come and go – notably the absurd claims that the US had developed bioweapons sites across Ukraine. But Putin’s core geopolitical framing of the war has remained consistent: Nato and the forces of the “collective west” represent an existential threat to Russia.

Given the popular notion of rival geopolitical blocs and the “no-limits friendship” between Moscow and Beijing, comparisons to the former cold war are commonplace. Commentators and academics are keen to scrutinise various similarities and distinctions. But there is an underappreciated comparison between Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and another act of aggression a century earlier: the Red Army’s invasion of Poland in 1920 under Vladimir Lenin.

Although more than 100 years ago, the Bolsheviks framed this conflict in strikingly similar terms to the conspiracies running through Russian propaganda today.

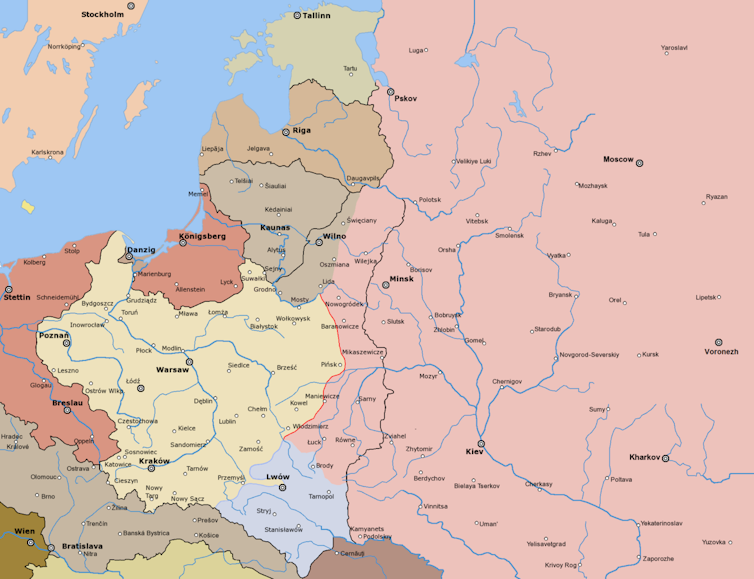

The Soviet-Polish war of 1919-20 was one of several overlapping conflicts commonly, though simplistically, known as the “Russian” civil war, sparked in the aftermath of the 1917 revolution. Following escalating fighting between Polish and Soviet forces from 1919 in Belarus, Lithuania, and later Ukraine, Lenin decided to press a rolling Red Army counterattack in the summer of 1920 into a full-blown invasion of Poland.

The plan was to seize Warsaw and “sovietise” the country, creating a “revolutionary bridge” that would eventually stretch as far as Germany. Considering the extent to which the Soviet military was already stretched and the hostile reception that awaited invading Red Army soldiers, this was a colossal risk. But, despite doubts from some senior Bolsheviks (most notably Joseph Stalin), Lenin was certain that Poland was on the cusp of a workers’ revolution.

Meanwhile, out-of-touch Polish Bolsheviks in Moscow gave support to Lenin’s misapprehensions that Polish workers would rise and side with invading Red Army soldiers. So the Soviet leader decided to take the gamble.

In the end, and in a moment sometimes depicted as a turning point in modern history, Lenin’s offensive came crashing down in spectacular defeat outside the gates of Warsaw in mid-August 1920. In a matter of days, Polish supreme commander, Józef Piłsudski, had successfully exploited the strung out Red Army forces.

The Polish Army smashed through its opponent’s overstretched lines, forcing them into humiliating defeat, later immortalised as the “Miracle on the Vistula”.

Capitalist encirclement

Before the Battle of Warsaw, not all Bolsheviks had agreed with Lenin that “sovietising” Poland was a realistic strategy. But the party leadership, as well as Soviet Russia’s foreign and intelligence commissariats and military establishment, were unanimous on one thing: Poland was not the primary enemy.

They pointed instead to the capitalist west. At the time this was represented by the “Entente powers” – Britain and France – who were, apparently, coordinating, supplying and sometimes giving direct orders to the Polish Army in an attempt to reverse the revolution.

In truth, Britain and France – which had been Poland’s closest allies since it was reconstituted as an independent state in 1918 – offered little tangible support in the Soviet-Polish war and had moved away from intervention in Soviet Russia by 1920. Nevertheless, the Bolsheviks grossly exaggerated the threat from the western powers. “All the Entente states are doing their utmost to incite Poland to make war against us,” Lenin remarked at a meeting of the central executive committee in February 1920.

It’s tempting to dismiss Lenin’s public addresses as purposeful propaganda. But the same conspiracies run through masses of internal Soviet correspondence. To take just a few examples, writing in private in 1919, Stalin described how a “single unified command” was preparing operations against Soviet Russia using bases in Riga in Latvia to the north, Warsaw in Poland, and as far as Chișinău in Moldova in the south.

Stalin later described to Leon Trotsky, again in private, that the Entente’s “hypnosis” was “extraordinarily strong” over the countries on Russia’s western borders: the Baltic States, Poland, and Romania. Chief diplomat, Georgy Chicherin claimed without evidence that British and French forces might launch parallel attacks against Soviet Russia, supported by Finland, the Baltic States and Italy.

A complicated anti-Soviet conspiracy loomed large in the Bolsheviks’ minds. Poland, in this fantasy, was seen as possessing little agency of its own – nothing more than a puppet of capitalist Britain and France.

Bolshevik fears of international conspiracies were not unique to the Soviet-Polish war. “Capitalist encirclement” was a deeply rooted conviction stemming from the international isolation of the 1917 Revolution. But the humiliating defeat to Poland in August 1920 – and the way the Bolsheviks explained this in conspiratorial terms – amplified an instinct to see “anti-Soviet blocs” everywhere.

Soviet military intelligence went on to write continuous inaccurate reports to this effect throughout the 1920s. And before Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Germany, Stalin – behind closed doors – identified a coalition of Poland and the Baltic States, backed by Britain and France, as the central threat to Soviet security.

Putin, of course, is not a Bolshevik and how much he believes his own propaganda is hard to determine. And while Poland received relatively little support in 1920, the same cannot be said of Ukraine today. But echoes in Putin’s rhetoric and Russian propaganda of an older Soviet worldview – exaggerating interventionist blocs encircling Russia while refusing to recognise the agency of Ukraine – precisely how Lenin once saw Poland – are hard to ignore.

![]()

Peter Whitewood receives funding from the British Academy and Hoover Institution, Stanford.