To be human is to wonder what happens after we die. Is there an afterlife? If so, what does it look like? But a question you may not have asked yourself is: what does the afterlife smell like? To ancient Egyptians, however, there were very specific answers, and new research has shed light on this aspect of their burial practices.

Analysis of the oils and resins in limestone jars that held the organs of Senetnay, a noblewoman of the 18th Dynasty who lived around 1450BC, has revealed a carefully formulated mix of ingredients.

Researchers have presented this as “the scent of the afterlife” in a scientific report. The smell will be revealed in an interactive exhibition at Moesgaard Museum in Denmark titled Ancient Egypt – Obsessed with Life, opening on October 13 2023.

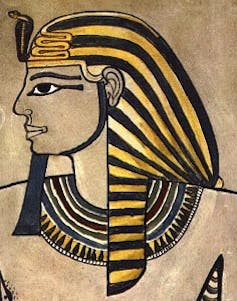

Senetnay’s role as a wetnurse to the future king Amenhotep II ensured her place in the afterlife and saw her buried in the Valley of the Kings. Unfortunately, her remains have not survived. But the embalming resin used for her preparation has. Its scent was both a reflection of her own status in royal circles and a statement of the king’s wealth and power.

A high-status scent

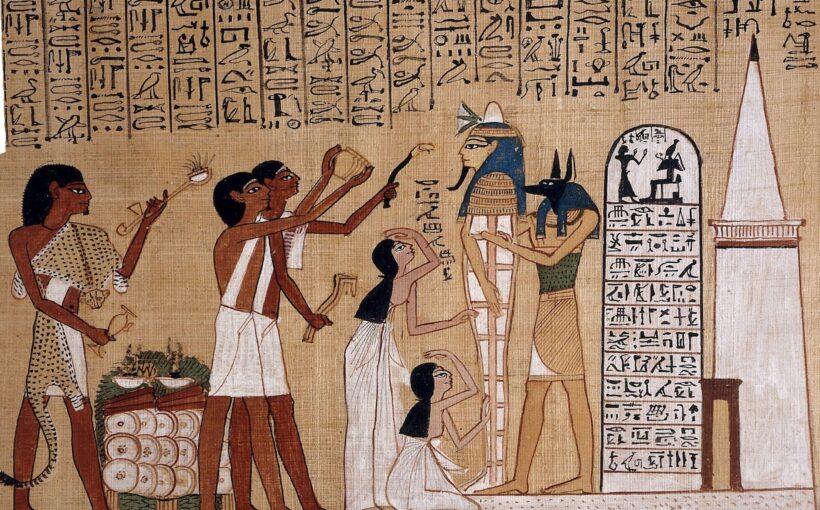

Amenhotep II inherited one of the largest empires ever known from his father, Thutmose III. Senetnay was fortunate to live at a time of great prosperity for Egypt and to be part of the king’s entourage. Her canopic jars (containers that preserved the viscera of the dead for the afterlife) were recovered from tomb KV42 by Howard Carter in 1900.

The resin is not typical of an ancient Egyptian burial – even a high status one – as it was extremely expensive, with ingredients from distant lands.

Such balms, resins and oils used in mummification provided pleasant aromas and practical functions in the preservation process, but also had spiritual significance.

This specific recipe seems to have been mixed specifically for Senetnay as it is different to other samples. She may have had some say in what was used – perhaps even her favourite scent.

The scent of the afterlife

Mummified human remains tend to smell relatively benign. The infusion of scented oils and resins has a lasting effect, especially in an undisturbed burial where the scent has been contained.

The salt and palm wine used in the preparation of the body itself also helped to preserve the properties of the other ingredients.

There is often a distinct fragrance of pine or cedar, with some spiciness from cloves, cumin and myrrh, and warm notes from plants, flowers and trees. Senetnay’s balm is based largely around beeswax, plant oil and tree resin, with extra fats, bitumen and other resins.

The ingredients are a snapshot of Egypt’s empire and reach – several came from a considerable distance. Larch tree resin is likely to have been obtained from the northern Mediterranean. South-east Asia (perhaps more specifically India) is present in what is possibly dammar tree resin.

The researchers have still to establish conclusively if dammar was used – if so, this is an indication of the extent of the ancient Egyptian trade route, stretching to the tropical forests of south-east Asia.

Oils and bitumen from cypress, cedar or juniper add layers of scent, preservative and antibacterial properties. Beeswax is both antibacterial and acts as a binder and sealant. Animal fat adds consistency and carries oils well, and the mixture is heightened with plant and flower oils such as sesame or olive.

The resulting balm would have been intensely fragrant and crucial for the survival of Senetnay’s remains. The written record confirms the close association of scent with life and death.

One ancient Egyptian word for a bouquet or garland was a homonym for life – ankh. A poignant and beautiful 12th Dynasty composition known, among other titles, as The Dialogue of a Man with his Ba (soul) says: “Death is before me today, like the scent of myrrh, like the scent of flowers.”

Scent at the museum

Scent is one of our most powerful senses, with the ability to transport us to another time or place by triggering memories, so it is an unusual but effective way to engage museum visitors with the past.

Smelling what the balm contained conveys much more than just a description would and it can enhance the experience for certain groups of visitors, such as the visually impaired, or those who engage more fully with such displays through an interactive approach.

Intangible aspects of ancient Egyptian funerary practice are by their nature difficult to research, and analysis of embalming materials has tended to focus on the body itself and its wrappings. However, some research projects have lately been attempting to address this gap in research, including concentration on the treatment of organs such as those of Senetnay.

The experience of an ancient funeral would have encompassed smell, sight, taste, sound, light, darkness and more. While we can reconstruct the process of embalming and burial through artefacts, we are doubtless missing very important aspects of the ritual that connects the deceased with their family, community and the ancestors they hope to join in the afterlife.

The luxuriousness of Senetnay’s provisioning for the afterlife should not obscure how profound and essential the materials and ritual were for her transfiguration in the tomb, complete and perfect for eternity, as fragrant as the gods.

![]()

Claire Isabella Gilmour does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.