At a press conference after talks with the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, this afternoon, Nato secretary general Jens Stoltenberg sounded like a man determined to take a “glass half full” attitude when he said that “every metre that Ukrainian forces regain is a metre that Russia loses”.

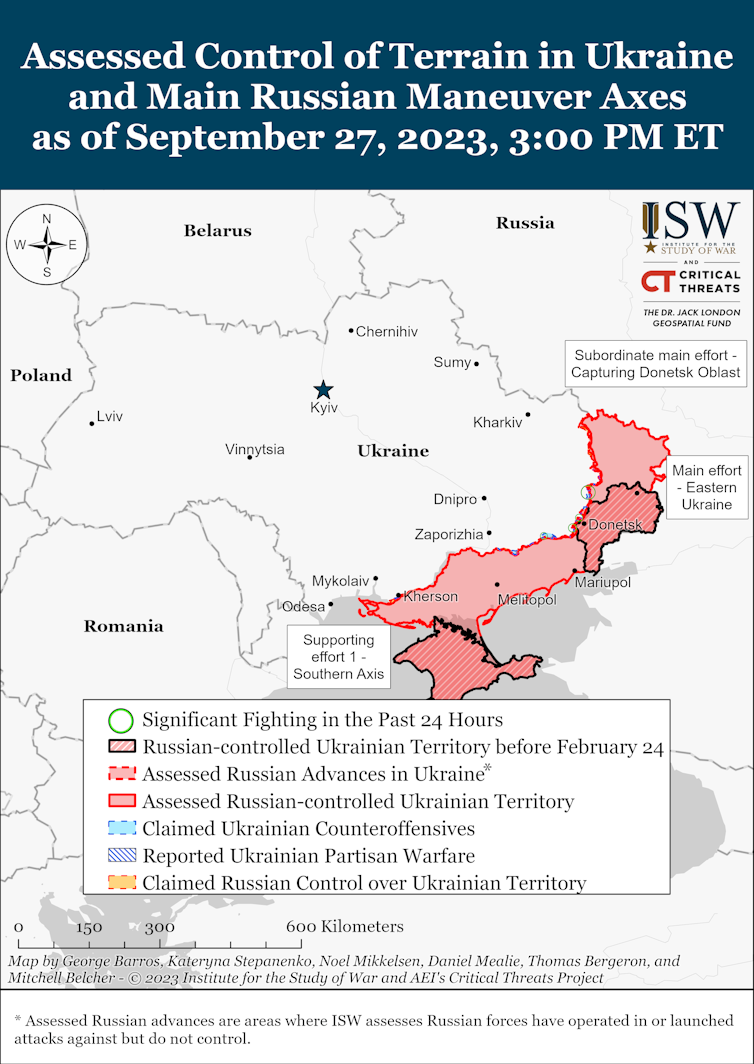

His statement, if a bit obvious, showed commendable optimism. Reports from the frontlines in Ukraine have been mixed over the past few months, with nothing like the lightning-fast territorial gains made by Ukraine in its late summer offensive last year, when it liberated vast swathes of territory occupied by Russia. Some of this was retaken only days after it had been declared part of the motherland by Vladimir Putin, who annexed four regions in the east and south on September 30 – only to hear that quite a lot of these regions were now Ukrainian soil once again.

This year, Kyiv’s planned counteroffensive was late coming, partly due to the slow delivery of western military aid. This gave Russia ample time to build imposing defensive fortifications. The sort of swift manoeuvring responsible for last year’s successful counterpunches have been nigh on impossible this year.

Since Vladimir Putin sent his war machine into Ukraine on February 24 2022, The Conversation has called upon some of the leading experts in international security, geopolitics and military tactics to help our readers understand the big issues. You can also subscribe to our fortnightly recap of expert analysis of the conflict in Ukraine.

It hasn’t helped that western commentators have continuously talked up Ukraine’s chances of a signifcant military success. Ukraine’s allies should manage their expectations, writes Frank Ledwidge, a lecturer in military strategy at the University of Portsmouth and former military intelligence officer.

Ledwidge points to mounting Ukrainian losses this year. The body count is significantly higher than last year, with more to come as Ukraine struggles to push Russian forces back literally metre by metre. Beware all the talk of “gamechanging weapons” and “breakthroughs”, he warns. This is going to be a long, bloody and bitter struggle, and there is no prospect of an end in sight.

This time last year, we were talking about Ukrainian morale being sky high and things being grim in Russia, where Putin had been forced to announce the first mobilisation since 1941 to shore up Russia’s faltering military. Then came the battle for Bakhmut – a “meatgrinder”, as it has been described, for both sides, but principally for Russia’s Wagner group mercenaries, 20,000 of whom are estimated to have been killed in the bid to take what was, in reality, a strategically insignificant target.

Alexander Titov, who researches Russian history and foreign policy at Queen’s University Belfast, visits Russia regularly and says the mood on the Moscow street in May this year was at rock bottom. Bad news from the front was amplified by the likes of the now late and unlamented Wagner group boss, Yevgeny Prigozhin, whose viral videos regularly savaged Russian military commanders for their shambolic conduct. Meanwhile, there was trepidation as the Russian people awaited Ukraine’s counteroffensive.

Titov was back in Russia last month and reports a far more buoyant mood there, given the apparent failure of the counteroffensive to score any significant breakthroughs. Now, says Titov, it is Ukraine that is having to strengthen its conscription laws – and a recent scandal concerning people bribing recruitment officers has hit morale hard. Russia’s annual round of conscription, meanwhile, has delivered 300,000 fresh troops from its military reserves without Putin having to resort to what would have been a deeply unpopular second mobilisation.

Diverse theatres of war

While things haven’t moved as quickly as Ukraine might have hoped on the battlefield, Kiev’s military has diversified its strategy by attacking Russian targets in the Black Sea region and Crimea. A missile strike on September 22 is reported to have killed 34 officers and wounded 105 others. Initially, the dead were said to include the commander of Russia’s Black Sea fleet, Admiral Viktor Sokolov – but this has been denied by the Kremlin, which has released an undated and unverified picture of Sokolov, apparently still alive.

Basil Germond, a maritime expert at the University of Lancaster, believes that this is akin to a second front in the war. Not only do these attacks undermine Russian morale, they have effectively denied it control of the Black Sea. This not only has implications for Russia’s grain blockade, but means Moscow will need to deploy troops away from the main defensive lines in the south and east of Ukraine.

Meanwhile, one of the Kremlin’s reasons to be more cheerful is the recent deal it struck with North Korea, enabling it to address its shortage of ammunition. And according to Robert M. Dover – a professor of intelligence and security at the University of Hull – there are other reasons the west needs to be concerned about Moscow’s ever-closer relations with Pyongyang.

Once of these, Dover writes, is the fact that both countries have highly developed and sophisticated cyber-warfare capabilities. We’ve already seen how North Korea’s Lazarus group of hackers has been able to steal tens of millions of dollars in cryptocurrency, and the potential to wreak havoc by hacking into western military systems could be extremely dangerous.

Conflict fatigue

As the war creeps towards its 600th day and the body count mounts on both sides, Kyiv’s allies in the west are also looking to their own depleted armouries, not to mention their national budgets. It has been calculated the US alone has spent or allocated US$113 billion (£92 billion) on supporting Ukraine, and the UK, the EU and Kyiv’s other allies have also strained their coffers. Meanwhile, the strain of increased energy and food prices has been heavy.

Stefan Wolff, from the University of Birmingham, and Tetyana Malyarenko, from the University of Odesa, have been watching for signs of combat fatigue among Ukraine’s allies, as well as anger from those countries in the global south who feel as if their concerns have been sidelined.

Zelensky’s visit to the US, where a growing number of Republicans are openly questioning Washington’s commitment to supporting Kyiv “whatever it takes”, as well as a recent row with Poland over Ukraine selling cheap grain to the disadvantage of its own farmers, are signs that there may be limits to the solidarity that was so evident last year.

Another country where support for Kyiv, once rock solid, looks to be crumbling is neighbouring Slovakia, which goes to the polls on Saturday. The election is too close to call, but one of the people most tipped to be able to form a coalition government is three-times former prime minister Robert Fico. Fico has said if successful, he will halt his country’s military aid to Ukraine.

As Veronika Poniscjakova, an expert in international relations and security at the University of Portsmouth, writes, it’s a campaign pledge which may mean Fico has to get into coalition with some extreme far-right partners. But with support for Ukraine falling among the Slovakian people, it’s certainly not a pledge that will lose him votes this weekend.

Another war with Russian fingerprints

While Russia has been busy in Ukraine – or perhaps because Russia has been busy in Ukraine – hostilities have erupted once again in the troubled Nagorno-Karabakh region. Azerbaijan launched a massive assault on September 19 on the mainly ethnic Armenian enclave.

Stefan Wolff recounts the history of this troubled region and tracks the motivations of Russia, once a staunch ally of Armenia. Moscow, he writes, may be preoccupied with its war in Ukraine, but Putin is no fan of Armenia’s prime minister, Nikol Pashinyan, so may not be dismayed at the mounting anti-government protests in Armenia’s capital, Yerevan, calling for him to

Writing as the flow of ethnic Armenian refugees across the Lachin corridor into Armenia grew steadily into a flood, Anna Matveeva – a visiting professor at King’s College London and expert in the post-Soviet space – took a broader look at the geopolitical implications of the 24-hour assault. Azerbaijan has its own enclave inside Armenia, Nakhichevan, which borders Turkey and Iran and is only accessible to Azerbaijan by air. Any peace deal over Nagorno-Karabakh, therefore, will have to involve Iran and Turkey as well as Russia, and could have consequences for the whole region.

![]()