To work in nature conservation is to battle a headwind of bad news. When the overwhelming picture indicates the natural world is in decline, is there any room for optimism? Well, our new global study has some good news: we provide the strongest evidence to date that nature conservation efforts are not only effective, but that when they do work, they often really work.

Trends in nature conservation tend to be measured in terms of “biodiversity” – that is, the variety among living organisms from genes to ecosystems. We treasure biodiversity not only for how it enriches society and culture, but also its underpinning of resilient, functioning ecosystems that are a foundation of the global economy.

However, it is well known that global biodiversity is decreasing, and has been for some time. Is anything we are doing to reverse this trend effective?

As part of a team of researchers, we conducted the most comprehensive analysis yet of what happened when conservationists intervened in ecosystems. These were interventions of all types, all over the world. We found that conservation action is typically much better than doing nothing at all.

The challenge now is to fund conservation on the scale needed to halt and reverse declines in biodiversity and give these proven methods the best chance of success.

First, the less good news

Globally, biodiversity is being depleted by human activities like habitat clearance, overharvesting, the introduction of invasive species and climate change.

To arrest its decline, people in various places have taken measures including creating protected areas, removing invasive species or restoring habitats, such as forests and wetlands. These efforts are interdependent with traditional stewardship of the world’s richest biodiversity by indigenous people and local communities. And in 2022, governments adopted new global targets to halt and reverse biodiversity loss.

Our team, led by the conservation organisation Re:wild, the universities of Oxford and Kent, and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, analysed the findings of 186 studies covering 665 trials of different conservation interventions globally over the course of a century.

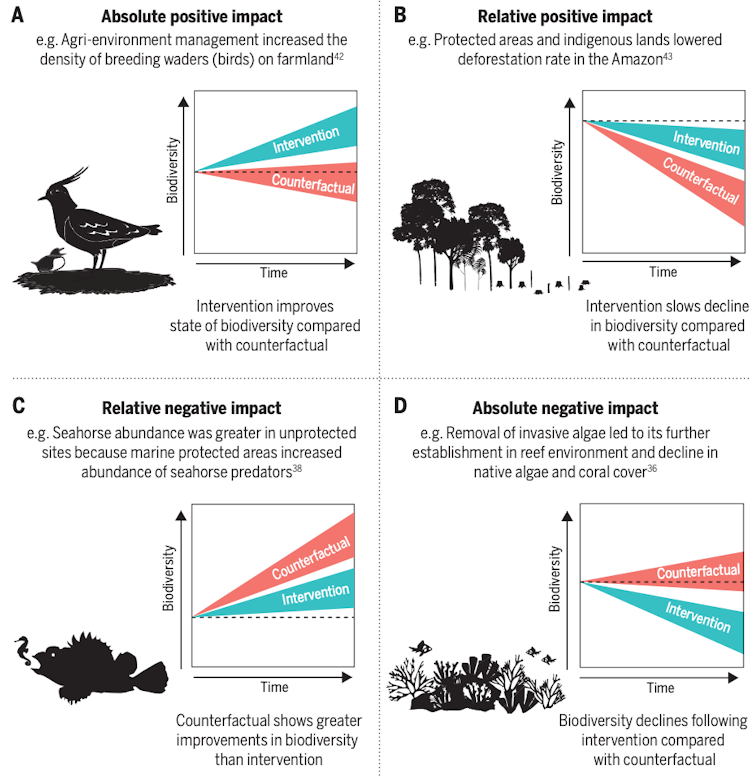

We wanted to understand whether the outcomes of these conservation actions improved on what would have happened without any intervention. Lots of studies have tried to compare the effects of conservation projects this way, but this is the first time such research has been combined in a single analysis to determine if conservation is working overall.

And now, the good news

What we found was extremely encouraging: conservation efforts work, and they work pretty much everywhere.

We found that conservation actions improved the state of biodiversity or slowed its decline in the majority of cases (66%) compared with no action. But more importantly, when conservation interventions work, we found that they are highly effective.

Examples from our far-reaching database included the management of invasive and problematic native predators on two of Florida’s barrier islands, which resulted in an immediate and substantial improvement in the nesting success of loggerhead turtles and least terns. In central African countries across the Congo basin, deforestation was 74% lower in logging estates subject to a forest management plan versus those that weren’t. Protected areas and indigenous lands had significantly less deforestation and smaller fires in the Brazilian Amazon. Breeding Chinook salmon in captivity and releasing them boosted their natural population in the Salmon River basin of central Idaho with minimal side effects.

Where conservation actions did not recover or slow the decline of the species or ecosystems that they were targeting, there is an opportunity to learn why and refine the conservation methods. For example, in India, removing an invasive algae simply caused it to spread elsewhere. Conservationists can now try a different strategy that may be more successful, such as finding ways to halt the drift of fragments of algae.

In other cases, where conservation action did not clearly benefit the target, other native species benefited unintentionally. For example, seahorses were less numerous in protected sites off New South Wales in Australia because these marine protected areas increased the abundance of their predators, such as octopus. So, still a success of sorts.

We also found that more recent conservation interventions tended to have more positive outcomes for biodiversity. This could mean modern conservation is getting more effective over time.

What comes next

If conservation generally works but biodiversity is still declining, then simply put: we need to do more of it. Much more. While at the same time reducing the pressures we put on nature.

Over half of the world’s GDP, almost US$44 trillion (£35 trillion), is moderately or highly dependent on nature. According to previous studies, a comprehensive global conservation programme would require an investment of between US$178 and US$524 billion. By comparison, in 2022 alone, subsidies for the production and use of fossil fuels – which are ultimately destructive to nature as fossil fuel burning is the leading cause of climate change – totalled US$7 trillion globally. That is 13 times the upper estimate of what is needed annually to fund the protection and restoration of biodiversity. Today, just US$121 billion is invested annually in conservation worldwide.

Potential funding priorities include more and better managed protected areas. Consistent with other studies, we found that protected areas work very well on the whole; studies that highlight where protected areas are not working often cite ineffective management or inadequate resources. More large-scale investment in habitat restoration would also help according to this new research.

Our study provides evidence that optimism for nature’s recovery is not misplaced. Though biodiversity is declining, we have effective tools to conserve it – and they seem to be getting better over time. The world’s governments have committed to nature recovery. Now, we must invest in it.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 30,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

![]()

Joseph William Bull has received funding from Defra and the EU Horizon grant scheme.

Jake E. Bicknell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.