Amid new targets of 1.5m new homes over five years, the Labour party has pledged to review the planning rules which dictate where housing in England can be built. The shadow chancellor, Rachel Reeves, has said that “a common-sense approach” to deciding quite what land is worth protecting and what can sensibly be used to create more housing was crucial.

This may put Labour at odds with many Conservative politicians in the UK, who have long defended the greenbelt, the protected land that encircles the country’s largest cities, including London, Newcastle and Manchester. The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities’s latest long-term plans for housing prioritise urban development of brownfield sites (abandoned or underutilised industrial land) over so-called greenbelt “erosion.”

The notion of “concreting over the countryside,” as Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has put it, is politically loaded. Yet, elements of the Conservative party itself are beginning to see that this oversimplifies the issue. As former housing minister Brandon Lewis has said at a fringe event at the Tory conference, the concept “needs to be reviewed and changed”.

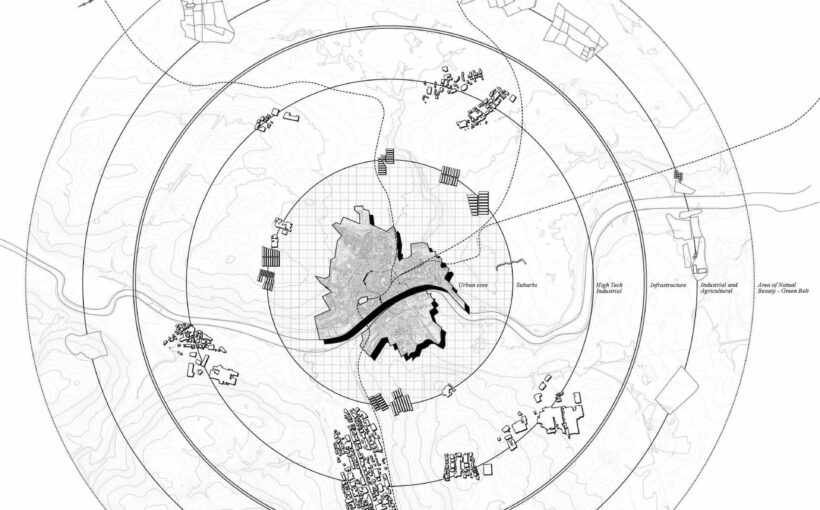

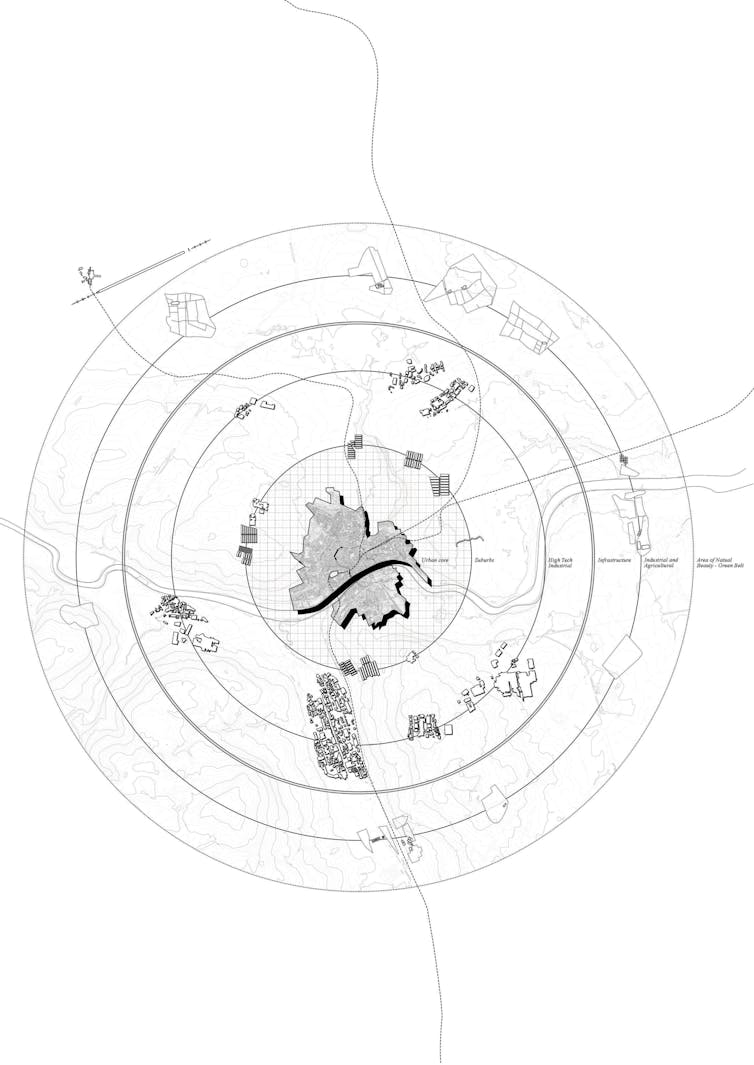

It no longer makes sense to prioritise the city centre over its peripheries because quite what is in the city, and what is outside it, is no longer clear. Multiple factors have seen the city extend into a continuous periphery. These include uneven urbanisation and geo-engineered landscapes, changing working patterns and locations and the perceived conflation of nature with culture.

Our research looks at how to rethink the urban-nature divide. We have found that design that focuses on urban peripheries in socially diverse and sustainable ways can benefit residents, combat climate change and tackle the housing crisis.

The politics of ‘urban sprawl’

In his long-term housing policy, Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Michael Gove has made the connection between urban planning, aesthetic standards and climate change. He argues against what he and many before him have termed “urban sprawl”. Instead, making the city centre more dense, he says, will “enhance economic efficiency, free up leisure time and also help with climate change”.

In city planning terms, “density” refers to the degree of human activity and occupation in a defined unit of urban space. It is, of course, an important measure. Our research shows, however, that what matters most is not the numbers of people and businesses in a city, but the quality of the space in which they operate.

Housing is an inherently political issue. Shelter, the housing charity, states that 17.5 million people are trapped by the housing emergency. According to the Centre for Cities thinktank, Britain has a backlog of 4.3 million homes missing from the national housing stock. This analysis shows that it would take at least 50 years to fill this deficit, if the government’s current target to build 300,000 homes a year in England is met. And it won’t be: homes are being built at approximately half this rate.

However, in 2013, the economist Paul Cheshire wrote that what he termed “the greenbelt myth” was, in fact, driving the housing crisis. “Contrary to popular perception,” he said, “less than 10% of England is developed. And of what is developed much less than half is ‘covered by concrete’.”

Instead, Cheshire proposed that there be selective building on what he termed “the least attractive and lowest amenity parts of greenbelts.” Not only are these areas close to cities where people want to live, but building on brownfield land in the greenbelt or repurposing derelict buildings might begin to alleviate the housing crisis, including problems of affordability, for generations to come.

How urban peripheries can work for people and the environment

To combat climate change and tackle the housing crisis, cities need to be allowed to expand with coherent planning – that includes good public transport, well-designed public spaces and high-quality housing.

In Italy, the post-war district of Gallaratese, which lies 7km north-west of the centre of Milan, features medium-scale apartment blocks, good social amenities and high-quality, well-connected public transport. People living there have access to small parks and public gardens, places to sit and shop.

This affords the public realm a certain dignity that is often lacking in in Britain. People benefit from better infrastructure for commuting into the city centres – not just traffic lanes for cars, but metro, tram and train connections, with coherently designed outdoor public space.

In Austria, Seestadt Aspern, a newly developed extension of Vienna, has been characterised as a “city within a city.” It is compact, yet full of public spaces. The project is conceived with job creation, housing and metro-line extension as priorities.

Our research suggests introducing, to periphery design, the kind of buildings more associated with inner-city design. To date, housing in suburban planning in England has largely revolved around the detached single-family home. This ultra-low density building type uses lots of land and is firmly reliant on fossil-fuel heavy private transport.

Focusing instead on what we have called the urban villa might be an alternative. The urban villa aims for a synthesis between the city apartment and the single-family home. Think, a number of apartments in a freestanding house, no more than five storeys, surrounded by a garden.

Suburban planning that centred on this type of housing – which combines urban density with a connection to green space and the public realm – could create a denser, more attractive and, crucially, more sustainable alternative to the way city outskirts are currently planned.

The housing crisis is inextricable from the climate crisis. The environment is most demonstrably in crisis in urban peripheries. It is where the collapse of a coherent urban order takes place, where big bits of transport infrastructure meet fields and suburbs. It’s often where marginalised communities are pushed.

Ultimately, Cheshire was right. The dual housing and climate crises are exasperated by the failure to resolve the greenbelt argument.

What is built around urban cores is crucial to a truly sustainable and equitable solution – for both people and the environment. But, doing so in a way that is beneficial to both residents and the environment requires a shift in government policy and public imagination.

As more and more people cluster around cities in search of work, or a better balance between home and work life, those areas that are now peripheral will become central. Quite under what conditions they live and work there is a matter that demands urgent attention.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.