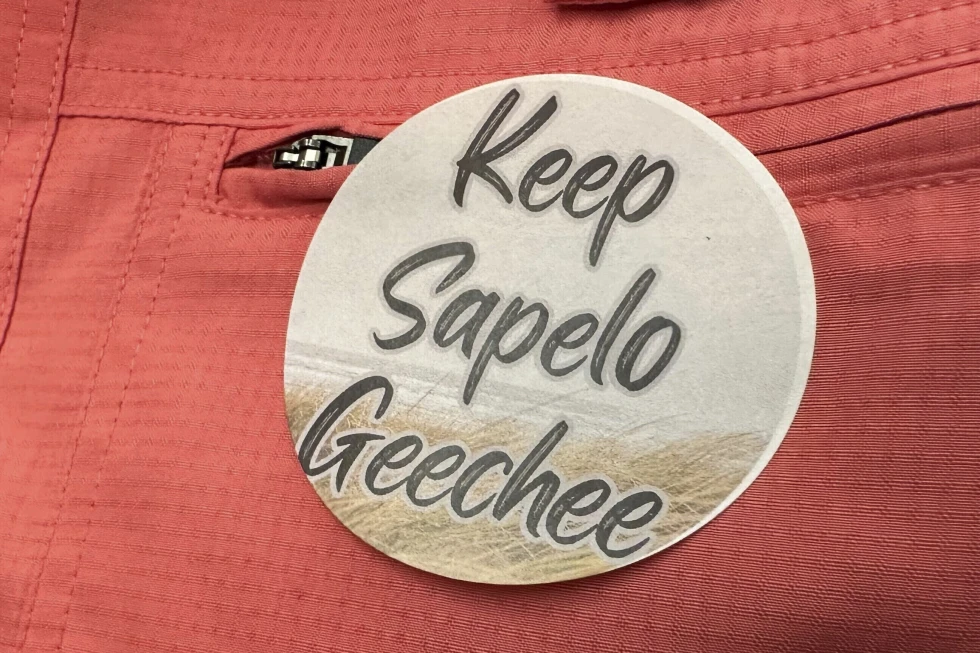

Black residents of a tiny island enclave founded by their enslaved ancestors off the Georgia coast have filed suit seeking to halt a new zoning law that they say will raise taxes and force them to sell their homes in one of the South’s last surviving Gullah-Geechee communities.

The civil lawsuit was filed in McIntosh County Superior Court a month after elected county commissioners voted to double the size of houses allowed in Hogg Hummock, where a few dozen people live in modest homes along dirt roads on largely unspoiled Sapelo Island.

Black residents fear larger homes in the community will lead to property tax increases that they won’t be able to afford.

County officials approved the larger home sizes and other zoning changes Sept. 12 after three public meetings held five days apart. Well over 100 Hogg Hummock residents and landowners packed those meetings to voice objections, but were given just one chance to speak to the changes.

The lawsuit accuses McIntosh County officials of violating Georgia laws governing zoning procedures and public meetings, as well as Hogg Hummock residents’ constitutional rights to due process and equal protection. It says county commissioners intentionally targeted a mostly poor, Black community to benefit wealthy, white land buyers and developers.

The residents’ attorneys are asking a judge to rule that the new zoning law “discriminates against the historically and culturally important Gullah-Geechee community on Sapelo Island on the basis of race, and that it is therefore unconstitutional, null, and void,” the lawsuit says.

It was filed Thursday on behalf of nine Hogg Hummock residents by lawyers from the Southern Poverty Law Center as well as Atlanta attorney Jason Carter, whose grandfather is former President Jimmy Carter.

Adam Poppell, the attorney for McIntosh County’s government, did not immediately return phone and email messages Monday.

About 30 to 50 Black residents still live in Hogg Hummock, which was founded generations ago by former slaves who had worked the island plantation of Thomas Spalding. Descendants of enslaved island populations in the South became known as Gullah, or Geechee in Georgia, whose long separation from the mainland meant they retained much of their African heritage.

Hogg Hummock, also known as Hog Hammock, sits on less than a square mile (2.6 square kilometres) of Sapelo Island, about 60 miles (95 kilometres) south of Savannah. Reachable only by boat, the island is mostly owned by the state of Georgia.

The community’s population has shrunk in recent decades. Some families have sold land to outsiders who built vacation homes. New construction has caused tension over how large those homes can be.

Residents said they were blindsided in August when McIntosh County officials gave notice of proposed changes to ordinances that had limited development in Hogg Hummock for three decades. Less than a month later, county officials held just two meetings prior to commissioners taking a final vote.

Despite vocal opposition from Black landowners, commissioners raised the maximum size of a home in Hogg Hummock to 3,000 square feet (278 square meters) of total enclosed space. The previous limit was 1,400 square feet (130 square meters) of heated and air-conditioned space.

Commissioners who supported the changes said the prior size limit based on heated and cooled space wasn’t enforceable and didn’t give homeowners enough room for visiting children and grandchildren to stay under one roof.

The lawsuit says county officials illegally sought to limit Hogg Hummock residents’ access to the three September meetings focused on rezoning their community. Residents were given a public hearing to address the county zoning board Sept. 7, but had no chance to speak before the county’s elected commissioners who cast the final vote.

Copies of the proposed zoning changes made public in advance of those meetings didn’t clearly mark what language would be added and what wording would get deleted from the existing ordinance, the lawsuit says.

Many Hogg Hummock residents rely on a state-operated ferry to travel between the island and the mainland. All three county meetings on the zoning changes were scheduled in the evenings after the last ferry was scheduled to depart. Though county officials arranged for a later ferry, the lawsuit says, it happened too late for some who stayed on the island to change their minds.

“The Board’s actions denied (residents) adequate notice and an opportunity to be heard at a meaningful time and in a meaningful manner,” the lawsuit said, and therefore deprived them of “protected property interests without due process of law.”

Outside of court, Hogg Hummock residents are gathering petition signatures in hopes of forcing a special election that would give McIntosh County voters a chance to override the zoning changes.

Georgia’s constitution allows citizens to call such elections with support from 10% to 25% of a county’s registered voters, depending on its population. In McIntosh County, roughly 2,200 voter signatures are needed to put Hogg Hummock’s zoning on a future ballot.