This article is based on an interview for The Conversation Weekly podcast on the subvertising movement.

In the lead up to Black Friday, we have been bombarded with adverts from brands offering big discounts off various things we probably don’t need, and may not even be able to afford amid an ongoing cost of living crisis.

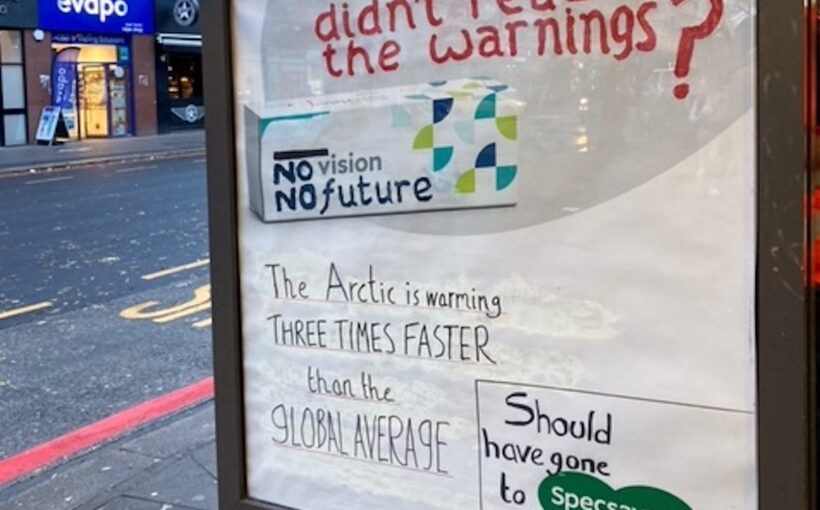

But a group of activists have used this moment of shopping frenzy to make a wider point about the unsustainability of consumer capitalism through subvertising – or subverted advertising. A subvert often uses the language and style of a brand itself as parody. It’s also known as culture jamming, or brandalism – a mashup of the words brand and vandalism.

The Zap Games was an anti-advertising festival which ran for two weeks from 11 to 24 November, in which people were invited to alter a public advertising space in a creative way to protest against the unbridled consumerism swirling around on Black Friday.

Zap stands for Zone Anti-Publicitaire, French for anti-advertising zone. Launched in Belgium in 2021, the Zap Games have become a global competition run by Subvertisers International. There are awards under categories including sculpture, digital screens and most family friendly intervention.

In one simple example which appeared in the UK city of Birmingham, somebody had created a big poster, tailored to the size of an advertising slot in a bus stop panel, which read: “Don’t buy stuff. Enjoy your friends.” Another, in the style of a John Lewis advert, read “100% saving if you don’t buy anything.”

Subvertisers International is a movement of like-minded activists around the world, which includes Brandalism, a collection of people, artists and activists. The group has been called a number of different things from eco-activists to guerrilla groups, to hackers and street artists.

The movement and its members have attracted media and public attention – and for me that’s particularly important when thinking about the climate crisis. If the point of advertising is to sell, the point of subvertising is to open up that message and attach a whole range of meanings to it, especially related to social and environmental justice topics which are increasingly attracting advertising interest.

It’s a very complicated thing to resist mass consumerism. And it’s as complicated to think and act on the environment – but these groups have been doing so for a number of years.

Environmental narratives

Brandalism began in 2012 during the London Olympics where members started replacing outdoors advertising panels with original artworks. From there they scaled up to a large actions during the COP21 climate talks in Paris in 2015, which is when I first came across the movement. One prominent poster was a parody of an Air France advert, part of which read: “Tackling Climate Change? Of course not. We’re an airline.”

Their main aim during the COP21 action was to critique the corporate sponsorship of the climate talks. In my early research on subvertising, I looked at all of their artwork and selected a purposeful sample which I felt demonstrated the variety of different environmental messages the actions were putting across. One was a critique of corporate greed, another about inadequacy of politicians to challenge the status quo, and another aimed at the role of consumers.

I also came across other kinds of environmental narratives which were more poetic, such as the Earth in mourning. One subvert, for example, showed an image of the Earth withering away, while others were short poems marking the grief brought on by the climate crisis. Finally, another theme concerned people wanting to declare their commitment to the environment and environmentalism. These were poetic nudges: “Let’s stop buying things. Let’s start like spending more time together. Let’s be more connected, rather than disparate.”

Listen to the full interview with Eleftheria Lekakis on The Conversation Weekly podcast.

In further research on advertising activism and advocacy I interviewed 24 subvertisers in seven countries about their motivations. One was a Paris-based citizen who documented the lives of people who put up public advertising and are paid very little money for it. He was also advocating for less advertising in public spaces. This is more common in France where groups such as Résistance à l’Agression Publicitaire, or resistance against advertising, have lobbied to restrict the presence of advertising in public spaces since the early 1990s. This group also provides schools with pedagogical kits to get students to think about advertising critically.

Another member of Subvertisers International, Democratic Media Please, which is based in Australia, is more interested in damaging outdoor advertising. When I spoke to him he also stressed the significant fact that advertising is the main source of funding for the majority of media organisations and it’s very hard in Australia to come across independent journalism that is not swayed by the commercial interests of its sponsors.

The environment is definitely a key concern of many subvertisers. But while a number of different artists I interviewed talked about the significance of the environment as a key driver in their activism, they told me they never really divorced it from issues of gender and race. Subvertising tries to weave together these concerns. Sometimes we’ve seen campaigns concerned with the whiteness of popular culture, for instance, and increasingly, especially in actions such as the Zap games, you see a lot more interconnectedness when it comes to environmentalism and race and gender politics.

The subvertising movement invites us to think and act critically towards advertising industries, practices and messages. Doing so is central to imagining and creating a future that is inclusive, sustainable and just.

![]()

Eleftheria Lekakis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.