November 22 2023 marks 60 years since US president John F. Kennedy was shot and killed as he rode in a motorcade through Dealey Plaza in downtown Dallas, Texas. The event shocked the world. But it also sparked the minds of filmmakers, authors, artists and conspiracy theorists. To commemorate the anniversary of one of the most famous assassinations in history, we asked seven experts to recommend a film, artwork, book, resource or place that can help to understand the event – and its myriad consequences.

1. JFK (1991)

Historians of the assassination of John Kennedy divide into two camps. There are those who accept the official version provided by the Warren Commission – that a lone gunman, Lee Harvey Oswald, was responsible for the murder and was himself assassinated by Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby before he could face trial. And there are those who subscribe to one of the various conspiracy theories.

The most famous of those conspiracy theories emerged at the end of 1991 when the film JFK by maverick director Oliver Stone was released. That it became so widely discussed was due to the power of film, Stone’s bravura reputation (having won Oscars for his recent films on the Vietnam War) and the reception of JFK – which received eight Oscar nominations.

JFK told the true story of New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison (Kevin Costner) who brought a case against businessman Clay Shaw for conspiracy in Kennedy’s murder. But Stone also used the film to develop the idea that the assassination represented a coup. In the film, generals and the CIA plot Kennedy’s murder as they were enraged with Kennedy’s Cold War policies, particularly with what Stone portrayed as his plan to withdraw from the Vietnam War.

Most significantly, the debate over the movie influenced politicians on Capitol Hill to pass the Assassination Records Collection Act, expediting the release of many hitherto classified documents on the assassination.

_by Mark White, professor of 20th century US history, Queen Mary University of London

2. John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection

Three decades after the Kennedy assassination, the US Congress passed a law mandating the release of all assassination-related material. The collection comprises over 5 million pages of state files, photos, recordings and artefacts.

The catalyst had less to do with transparency than countering the impact of Oliver Stone’s conspiratorial 1991 movie, JFK. Public scepticism about what actually happened in Dallas was high, despite the official inquiry by the Warren Commission publishing its 888-page report and 26 volumes of evidence in 1964. To curb conspiracy theories, the JFK Records Act made it law for the US government to disclose all its records (apart from items vital to national security).

Anyone with an internet connection can browse the collection, with 99% now public. Less than a month ago, a handful of the final files were released by the US president, Joe Biden. It is the most systematic revelation of state records in modern history. Yet the notion that more government information enables better public understanding confronts the fact that more than 60% of Americans continue to believe Lee Harvey Oswald did not act alone.

by Kaeten Mistry, associate professor of American history, University of East Anglia

3. Flash-November 22, 1963 by Andy Warhol (1968)

Flash-November 22, 1963 is a portfolio of works by the pop artist Andy Warhol. It will be displayed at the Telfair Museum in Savannah, Georgia to mark the 60th anniversary of the Kennedy assassination.

Warhol created the pieces as part of his persistent interrogation of the cultural role of image and media. He said JFK was “handsome, young, smart, but it didn’t bother me that much that he was dead. What bothered me was the way television and radio were programming everybody to feel so sad. It seemed like no matter how hard you tried, you couldn’t get away from the thing.”

It’s worth wondering if the programming has continued, or even intensified, today.

by Peter J. Ling, emeritus professor of American studies, University of Nottingham

4. Love Field (1992)

Love Field forgoes the conspiracy theories, governmental intrigue and macho histrionics of films like JFK (1991) and Ruby (1992). Set in the days surrounding the assassination, it instead focuses on the intertwining lives of a white woman, Lurene Hallett (Michelle Pfeiffer) and black man, Paul Cater (Dennis Haysbert), against the backdrop of the era’s upheavals.

Love Field portrays the day of the assassination as both a national trauma and instigator of its central protagonist’s quest for self-discovery. Lurene, a Jackie Kennedy-obsessed hairdresser from Dallas, boards a bus to attend JFK’s funeral, but her “journey” soon encompasses her escaping an oppressive marriage and rethinking her entire life plans. A chance meeting and subsequent relationship with Paul who, along with his daughter, is on the run from the authorities, introduces Lurene to the racism from which she has long been sheltered.

In its portrayal of an unequal society divided by class, race and gender, Love Field goes some way to unravelling the glossy, nostalgic image of JFK’s administration, often promoted by politicians of the 1990s. Though its social analysis does at times slip into cliche, strong performances from Pfeiffer and Haysbert nonetheless make Love Field an emotionally charged, thought-provoking exploration of personal lives and politics circa 1963.

by Oliver Gruner, senior lecturer in visual culture, University of Portsmouth

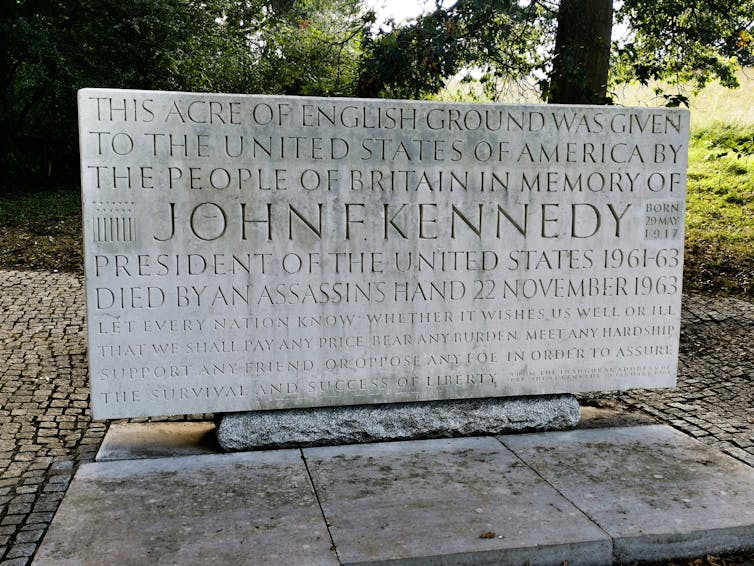

5. The Runnymede Memorial, Windsor, England

Britain’s memorial to Kennedy, designed as a site of reflection by architect Geoffrey Jellicoe, stands on the banks of the Thames at Runnymede. It consists of a stepped, woodland path leading up to a large slab of Portland stone on which are inscribed words from Kennedy’s inaugural address.

Speaking at the dedication ceremony in 1965, Queen Elizabeth II described JFK as a man “who in death my people still mourn and whom in life they loved and admired”. In fact, Britain launched an appeal to raise £1 million to build the monument as a symbol of the “special relationship” with the US. But popular ambivalence about the American superpower and the wealthy Kennedy clan induced Harold Wilson’s Labour government to contribute half this amount to avoid embarrassment.

The memorial can therefore be interpreted as evidence of the public’s divided views on the American superpower, rather than of its vaunted affection for JFK.

by Robert Cook, emeritus professor of American history, University of Sussex

6. 11/22/63 by Stephen King (2011)

What if John F. Kennedy hadn’t died on November 22 1963? Would the US, the world, be different, better? That’s the question that drives Stephen King’s novel, 11/22/63. His protagonist, Maine high school teacher Jake Epping, has the chance to return to mid-20th century America to prevent Kennedy’s assassination.

Jake’s quest represents the ultimate liberal fantasy: that had JFK survived, the US might never have experienced the horrors of the Vietnam war, the damage of Nixon and Watergate and the myriad problems which stemmed from them.

King is too smart a writer to allow this to be the only theme of the book. He explores the light and darkness of the US of the late 1950s and early 1960s, reminding us that America was only great in that period for some of its citizens. As Jake tries to work out how to save Kennedy, the reader is also introduced to various elements of the conspiracy theories that have swirled around JFK’s death.

Does Jake succeed? No spoilers here, although long-time King readers will know that “be careful what you wish for” has been a regular theme of the author’s work. At the very least, King punctures the liberal fantasy about JFK’s death and reminds us that events are the result of more than the actions of a single person.

by Emma Long, associate professor of American history and politics, University of East Anglia

7. November 22, 1963 (2013) and The Umbrella Man (2011)

Errol Morris’ two short films, November 22, 1963 and The Umbrella Man, are a great introduction to some of the key issues surrounding the Kennedy assassination. Morris speaks with Josiah Thompson, a philosopher turned private investigator, about the problems facing anyone trying to research the assassination.

For example, what if an event is too bizarre to fit into a coherent narrative? Despite his years investigating the assassination and looking through the many films and photographs taken that day, Thompson says it is difficult to find any meaning behind the event. As he puts it: “we couldn’t put a ‘why?’ answer on it – it seemed to be beyond that.”

Thompson also describes the role of mass media in the aftermath, with amateurs photographing and filming the shooting, professional journalists sharing those images around the world and ordinary citizens interpreting the meaning of the photographs for themselves. This seems to anticipate some of the challenges we face today, with political polarisation, social media, and talk of “alternative facts” making it difficult for us all to agree on who can be trusted to tell truth from falsehood.

by Adam Koper, post-doctoral research fellow, Cardiff University

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

![]()

Adam Koper has received funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the Wales Institute of Social and Economic Research and Data (WISERD).

Kaeten Mistry has received funding from the AHRC (Arts and Humanities Research Council).

Peter Ling receives funding from the Arts & Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and Economic & Social Research Council (ESRC) and the British Academy.

Emma Long, Mark White, Oliver Gruner, and Robert Cook do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.