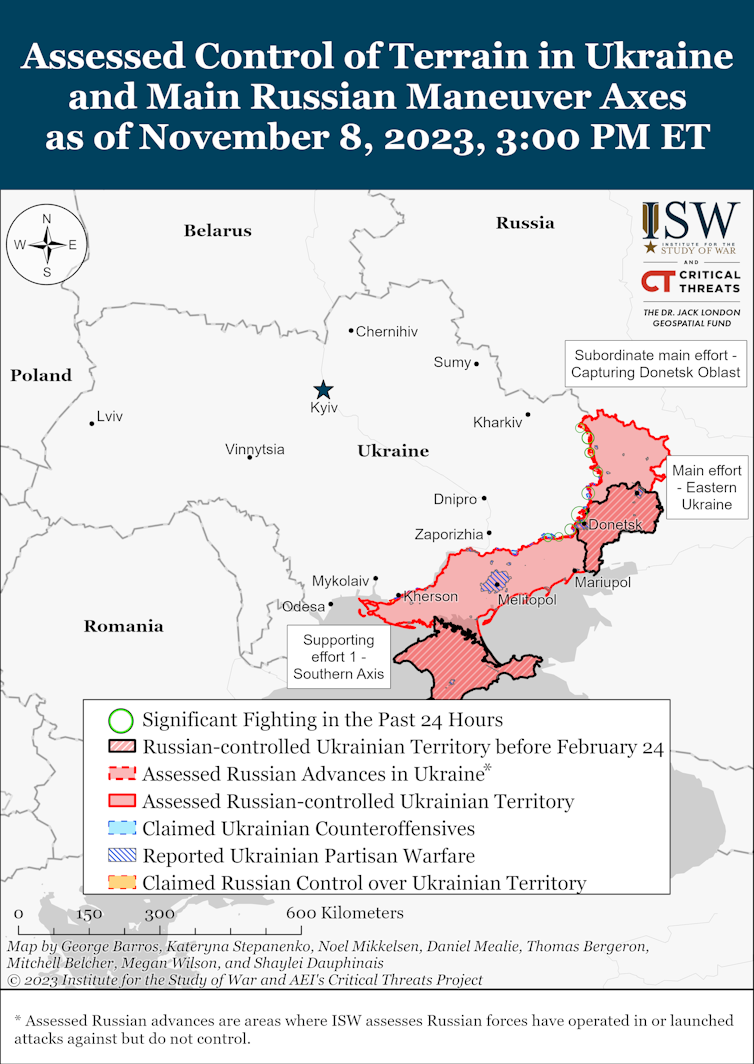

For the past month, the world’s attention has reeled at the violence in Israel and Gaza. Meanwhile, the war in Ukraine has ground on, day by day, metre by metre. Fierce fighting has continued in the north-eastern Donetsk region as a Russian offensive has attempted – thus far unsuccessfully – to consolidate its control by capturing the key town of Avdiivka, 20kms from the city of Donetsk.

Avdiivka was occupied briefly in 2014 by Vladimir Putin’s “little green men” (Russian troops fighting without insignia), but was swiftly retaken by Ukraine which has heavily fortified the town. Reports from the frontline are that Russia has committed significant forces to the offensive, and suffered heavy losses.

In the south, the progress of Ukraine’s counteroffensive remains slow, according to Ukraine president, Volodymyr Zelensky, who was speaking at Reuters NEXT conference this week. But he and his military brass have a plan: “I can’t share all the details but we have some slow steps forward on the south, also we have steps on the east,” he said. “And some, I think good steps … near Kherson region. I am sure we’ll have success. It’s difficult.”

Zelensky’s relentless optimism will be key in coming months, particularly with attention shifting to the Middle East, where the US has already committed funds. US President Joe Biden is already struggling to convince a sceptical Republican-dominated House of Representatives to keep faith with Kyiv, and – as Stefan Wolff and Tetyana Malyarenko note – there have been fresh calls from US and European officials (not identified by news reports) for Ukraine to negotiate a settlement with Russia sooner rather than later.

Wolff, an international security expert at the University of Birmingham, and Malyarenko, a professor of international relations at the University of Odesa, believe that with 2024 elections in Ukraine and polls saying that the vast majority of voters would not countenance giving up territory, it’s unlikely that Zelensky will agree to talks with Russia in the foreseeable future. But a great deal will depend on continuing western support.

Since Vladimir Putin sent his war machine into Ukraine on February 24 2022, The Conversation has called upon some of the leading experts in international security, geopolitics and military tactics to help our readers understand the big issues. You can also subscribe to our fortnightly recap of expert analysis of the conflict in Ukraine.

Winter is now also on its way, with all the hardships this will bring to the troops fighting in average temperatures ranging between -4.8 and 2°C. Marina Miron, a postdoctoral researcher at King’s College London, says that despite the insistence from both sides that they are well prepared to continue the fighting through the dark months, the lack of mobility that is inevitable from difficult ground conditions could bring both sides to a standstill. This of course, won’t play well with Ukraine’s western donors who want to see concrete evidence of successes on the battlefield.

Miron reports Ukraine’s insistence that its style of fighting, by small infantry detachments often using lighter equipment, is more suited to the hard conditions. But Russian troops, she writes, also know a great deal about fighting in winter conditions. The key is likely to be morale – both military and public. Ukraine’s ability to protect its energy infrastructure from Russian missile strikes will be critical.

Read more: Ukraine and Russia claim to be prepared for extremes of winter warfare – here’s what they face

Weaponising grain

Ukrainian sources reported that a Russian missile struck a civilian ship entering the Ukrainian Black Sea port of Odesa. Since Russia pulled out of the grain deal in July it has said it regards all shipping moving in and out of Ukrainian ports as legitimate targets. This poses a major threat to Ukrainian grain exports and global food security as winter approaches.

Alicja Paulina Krubnik, who is researching her PhD in political science at McMaster University in Canada, says the uncertainty surrounding food security caused by the war in Ukraine is contributing to price fluctuations that affect countries already struggling to feed their populations. This isn’t helped by speculation and short-selling, which has hurt farmers in countries such as Poland, whose moral and financial support has been so crucial for Ukraine since the war began.

Read more: Grain as a weapon: Russia-Ukraine war reveals how capitalism fuels global hunger

Cold war getting warmer

Tensions ratcheted up this week when Russia announced it was pulling out of an important cold war-era treaty which placed verifiable limits on certain types of military equipment that either side could deploy, such as tanks, aircraft and artillery pieces. In reality, the 1990 Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) had been dead in the water for some years – neither Nato nor Russia had been particularly scrupulous in observing its terms and the US stopped actively implementing the treaty in 2011, followed by Russia in 2015.

But Nato expert Kenton White, of the University of Reading, believes that Russia’s formal withdrawal from the treaty is a sign of an increasingly aggressive stance from Russia that should worry the Baltic states and Poland. Together with Moscow’s decision to withdraw from the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty in October (again, an agreement limited by the fact that numerous nuclear states – including the US – have never ratified it), White believes it represents the sort of mind games of which Putin is so fond. Anything that puts pressure on Nato unity is a boon for Moscow.

Read more: Russia’s decision to ditch cold war arms limitation treaty raises tensions with Nato

The diplomatic front

Whether hosting top officials from Hamas and Iran in Moscow less than three weeks after Hamas launched its attack on Israel was, as Israel insists, an “obscene step that gives support to terrorism and legitimises the atrocities of Hamas terrorists”, or a genuine attempt to take steps towards brokering some sort of peace deal remains to be seen. The fact is that Moscow has warm relations with all parties to the conflict in Gaza, certainly more so than Washington, which proscribes Hamas as a terrorist organisation.

Anna Matveeva, who researches international relations at King’s College London, highlights the fact that Israel has stayed neutral when it comes to Ukraine, refusing to send arms and abstaining on the UN vote condemning Russia for its invasion. She also notes that Hamas officials have visited Moscow three times since the war in Ukraine. Russia, she says, is probably the only country Hamas would trust to broker some sort of a peace deal.

Paradoxically, you could be forgiven for thinking that Russia benefits from the war in Gaza – it’s diverting world attention and US dollars from Ukraine. But securing a role as a peace broker would be a major feather in Putin’s cap and would play well with non-aligned countries such as India, South Africa, China, whose support Russia has been keen to secure.

Read more: The Israel-Hamas war benefits Russia, but so would playing peacemaker

Ukraine Recap is available as a fortnightly email newsletter. Click here to get our recaps directly in your inbox.

![]()