As the new year arrived in 2016, my home city of Newcastle upon Tyne was briefly the centre of global attention – for a puddle. The Drummond Puddle, as it was grandly known, was a watery hazard placed perfectly where converging footpaths funnelled a daily stream of victims to their doom. To the wonderment of the world, their fate was livestreamed over the internet to more than half a million viewers.

But puddles are not merely a source of delight for wicked-minded onlookers. We can all, surely, remember the joy of splashing in a puddle – a universal example of creative play and getting to know the environment.

And yet, the conservation value of these tiny sites is still largely unappreciated. For puddles can be valuable wildlife havens too.

One study of the invertebrate inhabitants of puddles in the UK countryside found a majority of these sites had a high conservation value, primarily due to the rare, specialist animals they hosted. Puddles may be commonplace, but their wildlife need not be.

Your own private pool

The tiny, fragmented, ephemeral world of puddles creates the ideal habitat for some species. The isolation and brief life of many of these mini-ponds keeps long-lived, larger predators and competitors at bay, opening up opportunities for more “live fast, die young” life.

In the UK, the most famous examples are the fairy shrimps of puddles on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire. Large areas of Salisbury Plain are given over to military training, and the churning tracks of tanks create many temporary pools that house these muddy lodgers.

The eggs of the fairy shrimp are resistant to drought. They remain dormant, but viable, for many years and are spread by the wind or, in the case of Salisbury Plain, are carried in the mud spattered on military vehicles.

When rain fills a track in the dried mud, fairy shrimp eggs hatch almost immediately. The shrimps grow quickly to lay a new generation of eggs before their puddle dries.

Other landscapes also harbour important puddles that we have helped to create. The Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall supports a network of trackways that date back to pre-historic times. Temporary pools have developed within these trackways, supporting rare specialist plants like the pygmy rush.

In the US, over the past decade, the rare clam shrimp has been found in puddles on the dirt surface of a gas pipeline road in New Jersey. The clam shrimp had only previously been identified in a handful of sites in the north-eastern US.

Puddle problems

Human activity may also be creating puddles in urban landscapes. The rapid urbanisation of Beijing has been linked with increasing the numbers of puddles in the Chinese capital, largely by accident as sites are demolished ready for new developments. As soon as the new build is started, however, these ponds are buried and lost.

The wildlife of urban puddles on roads and pavements has received much less attention compared with other urban habitats, such as flowerbeds or small ponds. But research in urban areas of south-east Poland shows that single-celled algae such as diatoms and desmids thrive in these puddle environments.

Studies in Brazil have also credited deforestation in the Xingu basin with driving “lentification” – creating water bodies that include puddles. Puddles in these more tropical regions of the world support the ominous presence of mosquito larvae.

The same safety from predators provided by puddles that benefits fairy and clam shrimps is also important to mosquitoes. In one study in Nigeria, Anopheles mosquito larvae were found in a higher proportion of road puddles than in other small water bodies.

Birds often look to exploit ponds and puddles, looking for drowned worms after prolonged rain. But worms are not that easy to drown (although it varies by species). So maybe the sorry, soggy specimens stuck in puddles are just unlucky, slowed down as they flounder in the water, becoming very obvious to birds with an eye for an easy meal.

Puddles are, however, not a positive substitute for the problems caused by urbanisation and habitat loss. In Poland, birds using road puddles for a wash risk being killed by traffic.

Planet puddle

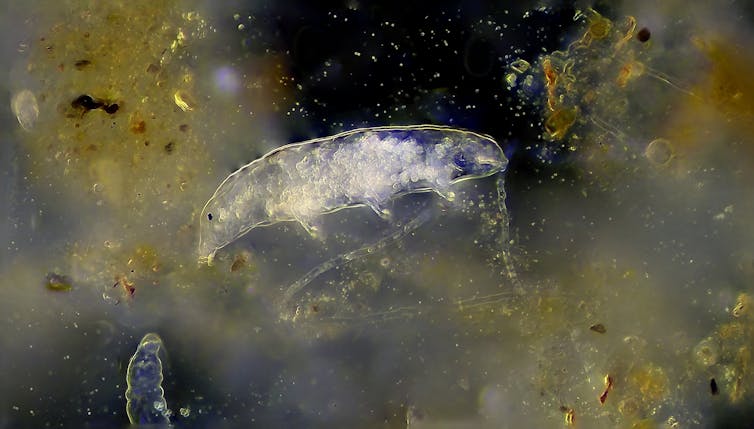

While we might be most familiar with the puddles of pavements and streets, there are natural puddle habitats too – and these are very widespread all over the planet. Puddles on ice sheets and glaciers called cryoconite holes are home to a cosmopolitan fauna of nematode worms, mites and the famously tough tardigrades.

Puddles also occur in deserts, often as tiny rock pools. By arranging sticky traps around these rock pools, researchers in South Africa showed how wind dispersal helps their inhabitants travel. As the rock pools dried, the traps caught wind-borne eggs blowing in the dust, carrying a mix of waterfleas, pea shrimps and mites.

Urban puddles might still be the toughest environment of all, compared with the puddles in these glacier and desert habitats. But in all cases, there is much more to puddles than meets the eye – not just tiny shrimps or marooned worms.

Some of the strange creatures they contain are much more conspicuous. Video coverage of the Drummond Pond in Newcastle in 2016 even captured some two-legged inhabitants that appeared to be large, mammalian and naked …

![]()

Mike Jeffries does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.