We think of Bermuda as a tiny paradise in the North Atlantic. But long before cruise ships moored up, prison ships carried hundreds of convicts to the island, first docking in 1824 and remaining there for decades.

Islands have long been places to deport, exile and banish criminals. Think of Alcatraz, the infamous penitentiary in San Francisco, or Robben Island in South Africa, which held Nelson Mandela. The French penal colony Devil’s Island was immortalised in the Steve McQueen film Papillon, while Saint Helena in the Atlantic is still remembered for Napoleon’s exile.

You may be familiar with the story of British convict transportation to Australia between 1788 and 1868, but the use of Bermuda as a prison destination is less well known. For 40 years, British prisoners worked backbreaking days labouring in Bermuda’s dockyards and died in their thousands.

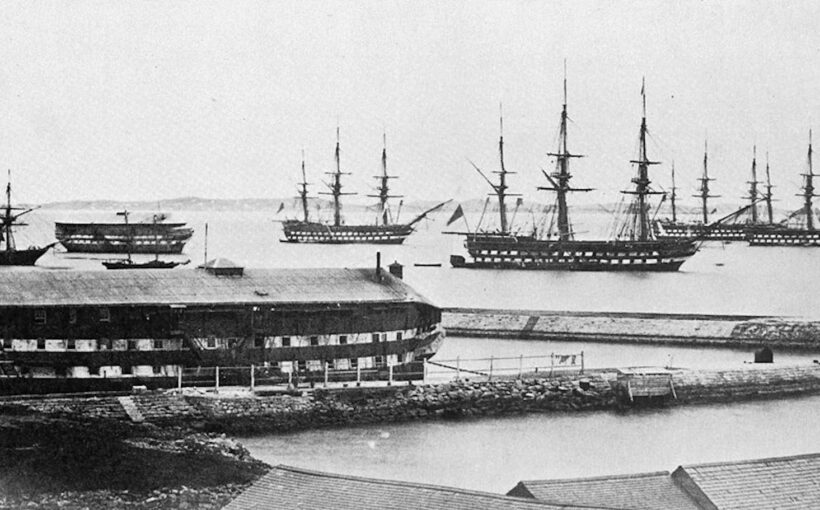

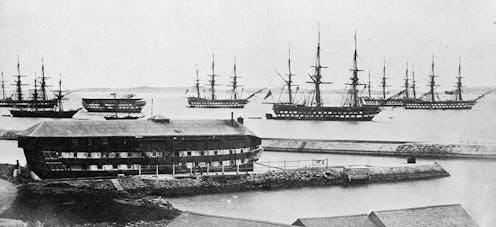

I research the lives of prisoners across the British Empire, and have a particular interest in notorious floating prisons known as hulks. I was surprised to discover that in addition to locations across the Thames Estuary, Portsmouth and Plymouth, the British government used these ships as emergency detention centres in colonial outposts across the 19th century, detaining convicts in Bermuda between 1824 and 1863 and Gibraltar between 1842 and 1875.

England has a long history of banishing its criminal population. In the 18th century, criminals were typically sentenced to seven years overseas in America. Many worked as plantation labourers in Maryland and Virginia, but the start of the American Revolution brought this practice to a halt.

Britain believed that the war with America would end quickly and in its favour, but as the war continued, prisons filled with people who had nowhere to go. There was no emphasis on reforming prisoners and releasing them back into society.

Britain found itself with a prison housing crisis, and turned to hulks to cope with rising numbers. Each could hold between 300 and 500 men, and they were nicknamed “floating hells” for their unsanitary and dangerous conditions.

Officials proposed several locations to send convicts, and ultimately settled on Australia. But the government felt that convict labour could be put to use in other colonies, and so began an experiment in 1824 to send men to Bermuda.

Convict workers

Bermuda had been colonised by British settlers since the 17th century, and was governed by various trading companies until 1684 when the Crown took over. Though only 20 miles long, the island was already extremely important to naval strategy. It was used as a refuelling station for British ships travelling to colonial outposts such as Halifax, Nova Scotia and the Caribbean.

But the naval dockyard needed modernisation, and rather than employ local workers, convicts – a cheap and easily mobilised workforce – filled the labour gap.

Bermuda didn’t have a large prison, so men lived on board the ships they had sailed on (seven in total). Local traders, shipbuilders and whalers objected, complaining in newspapers that the government was sending a “swarm of felons” to the island. The government offered a compromise: no convicts would remain on the island at the end of their sentences. Instead, they had to return home, or travel on to Australia.

Work on the island wasn’t without risk. Many were injured in the dockyards, others went blind from the reflected glare of the sun as they quarried white limestone.

Convicts were at the mercy of hurricanes which battered the ships and caused injuries. They were burnt by scorching temperatures and suffered sunstroke, and the island’s humidity caused respiratory problems and spread deadly fevers on board.

Rising tensions over work, religion and alcohol consumption led to fights between prisoners, their overseers and the militias that guarded them. Some attempted escapes by stealing boats and trying to board ships bound for America.

Bermuda also received people convicted in other British colonies, including Canada and the Caribbean. During the years of the great famine in Ireland (1845 to 1852), thousands of Irish convicts arrived on the island, many suffering from malnourishment. This diversity was striking when compared to prisons in England.

The experiment ended after 40 years, in 1863, when dockyard repairs were completed. The remaining hulks were scuttled or broken up for scrap, and convicts were transported to Australia and Tasmania, or home to England with their meagre pay in their pockets.

Prison islands today

Prison islands are naturally isolated and cut off from land – escape is virtually impossible. Then and now, they enable states to lay claim to land, facilitate trade and secure commercial ambitions. Islands have many strategic advantages and are frequently used as military bases. Now, many former prison islands are Unesco world heritage sites, and tourist destinations.

Bermuda’s history as a prison island has been largely forgotten, but this story shares parallels with today. Prisons are suffering from overcrowding, and governments still detain prisoners and others on islands and modified ships.

In Dorset, the Bibby Stockholm ship is housing asylum seekers, while the island of Diego Garcia, used as a UK-US military base is detaining Tamil refugees in the Indian Ocean.

The convicts who lived, worked and died in Bermuda are part of a larger global story of coercion and empire. The product of their labour was imperial strength, but for those sent thousands of miles from home and buried in unmarked graves, the brutalities of their experience should also be remembered.

![]()

Anna McKay currently receives funding from the Leverhulme Trust, and has previously received funding from the Irish Research Council and Arts and Humanities Research Council.