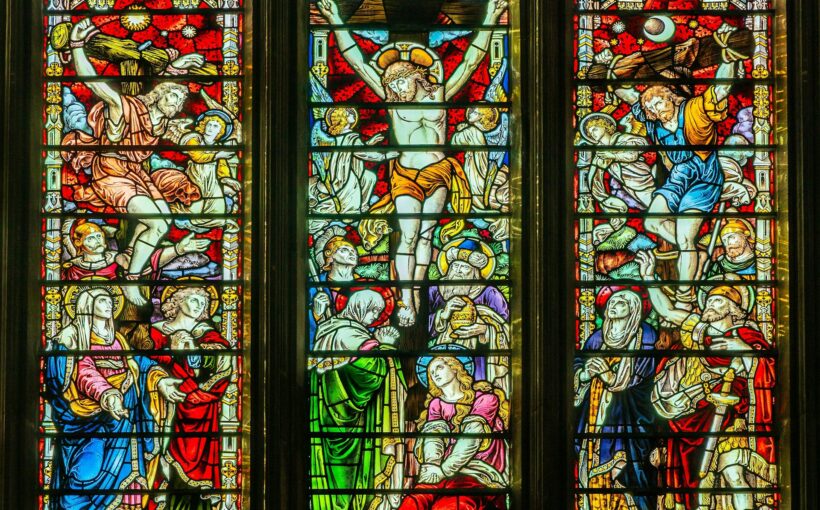

Easter is a time of mixed emotions. According to Church of England figures, up to a million people will go to church on Easter Sunday to celebrate the joy and hope of the resurrection of Christ. But in the three days before that, churchgoers in many traditions come face to face with the darkest moments of the Christian story: the betrayal Jesus faced at the hands of Judas Iscariot, his death on the cross and his burial.

Among the lesser known rituals of this pre-Easter period is an ancient exploration of darkness itself, known as tenebrae. Originally, this service took place late at night or early in the morning on the last three days of Holy Week, leading up to Holy Saturday (the day before Easter Sunday).

For at least 1,200 years, the defining feature of tenebrae services has been the gradual extinguishing of lights. Enclosed in an increasingly darkened church, worshippers are reminded of the three days Jesus spent in the tomb following his death.

My research shows that in the past it was actually quite common for worshippers to attend church in the middle of the night. Before electric light, sunset forced most daily activities to cease. Long winter nights afforded plenty of time both to sleep and to pray.

Darker than dark

Since medieval times, the tenebrae ritual has had the feel of a funeral. It features dirge-like chanting, doleful texts and a pointed avoidance of ornament.

The Latin verb tenebrare means “to darken” and this is probably the origin of the ritual’s name. A symbolic number of candles or lamps – historically this varied between five and 72, but is now most often 15 – is lit at the beginning of the service, and then, for each successive chant, reading or verse, one light is extinguished.

These are often placed on what is known as a “hearse” – a triangular or pyramidal frame that would also be placed above a coffin or tomb. (Only in the 17th century would this word be borrowed to describe a funeral vehicle.) By the end of the service, a single light remains, barely enough to see by.

The effect is hugely dramatic. There have been different interpretations of the ritual through the ages.

In his ninth-century commentary On the Ordering of the Antiphoner, the Frankish bishop Amalar of Metz understood the extinguishing of candles to represent the “the extinction of joy” brought about by Jesus’s crucifixion. Others saw a representation of the biblical figures and saints who had died bearing witness to this story, or a depiction of the waning light of Jesus the metaphorical sun.

Art objects have also provided layers of meaning. Standing some 25 feet tall, the giant 16th-century tenebrae candelabra of Seville Cathedral is comprised of a metal hearse topped with 15 candles and as many carved figures.

As each candle is extinguished, a person seems to disappear, as if the faith of Christians is draining away. Similar objects are found in many Catholic churches, including the one designed by Antoni Gaudi for the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona.

Some medieval churches used a hand-shaped snuffer made of wax to put out the candles. Signifying the hand of Judas, this underlined the theme of betrayal.

At the end of tenebrae, the final light is customarily hidden. In the eery, disorienting darkness that ensues, there is a long tradition of a loud sudden noise being made. This bang or clatter is known as the strepitus. People might slam a door, bang a book, stamp their feet or use percussive instruments.

The strepitus is thought to represent the confusion or shock the disciples experienced after Jesus died, or the earthquake that followed the crucifixion. Like many aspects of ancient ritual, though, the strepitus was probably functional in origin.

By definition, the days around Easter always enjoy the light of the moon. But finding your way out of an unlit church can be a struggle. It seems the original purpose of the sound, then, was to signal to the sacristan (the warden in charge of the church building and its contents) to reveal the hidden candle again, so that everyone could safely return home.

Inevitably, sometimes things got out of hand. In his Latin commentary on the liturgy, the 13th-century French bishop Guillaume Durand of Mende described a form of tenebrae service that ended with shouting, wailing and a “commotion of the people” as congregants enacted both the disciples’ grief and the ironic cheers of Jesus’s enemies. One 19th-century author reported a volley of musket-fire being used for the strepitus in Seville.

Today, the sounds of tenebrae are much more respectable. Performances by the eponymous, Grammy-nominated choir, Tenebrae, make a feature of candlelight and ancient church spaces.

The ritual has also inspired countless famous classical works. The 16th-century English royal composer Thomas Tallis crafted a sensuous vocal setting of tenebrae readings from the Old Testament’s Book of Lamentations.

In 1585, his younger Spanish contemporary Tomás Luis de Victoria published almost three hours’ worth of tenebrae polyphony. A more operatic style appears in François Couperin’s exquisitely anguished Leçons de ténèbres, composed around 1710.

More recent examples include Stravinsky’s angular and unrelenting Threni, a concert work from 1958, and Poulenc’s lesser-known Seven Tenebrae Responsories, commissioned by Leonard Bernstein in 1961.

Among the many cherished settings of one medieval Tenebrae text, O vos omnes (a Latin adaptation of Lamentations 1:12-18), is a version by Spanish and Puerto Rican composer Pablo Casals. Written in 1932, it is still widely performed today.

Casals was a peace activist as well as a cellist. His simple, heartfelt strains transform the words of the prophet Jeremiah into an impassioned plea for our troubled times: “Listen, all you peoples; look on my suffering.”

On Easter Sunday, many Christians will return from church having received a vital injection of hope for the world. But the tenebrae tradition, which some will also experience this week, has a useful role too. It helps us to come to terms with darkness in human history, and to find beauty even when it seems that hope itself is being extinguished.

![]()

Henry Parkes receives funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council.