From the late 1920s, London was home to a lively, if small, community of Jewish merchants from Afghanistan and central Asia. Most spoke Judaeo-Persian, popularly known as Bukharian Tajik. Many were fluent in Russian.

Hailing from established merchant families in Bukhara, Samarkand, Kabul and Herat, these immigrants traded in furs, carpets, cotton and wool. They maintained commercial relationships with their Muslim counterparts back home, especially Turkmen sheep farmers.

The many poorer Jews living in the region worked as distillers, builders, tailors, carpenters, itinerant peddlers and druggists.

In the years following the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, many Jewish merchants in central Asia crossed into Afghanistan and travelled on to British India. “I am a cloth merchant of Bokhara”, Sewai Hafaiz, aged 35, told the British official who interviewed him in the border city of Peshawar in November 1926, according to the India Office records. “I and Abraham have brought 24,000 karakul [lamb] skins for sale. We will sell them here or Bombay, or else take them to London.”

I have interviewed the descendants of these Jewish merchants, who have shared memories of life in post-war London. As I show in a recent article, their knowledge of furs – and close ties with Muslim contacts in Afghanistan and Pakistan – sustained a vibrant international trade for the better part of the 20th century.

Central Asian trading routes

Among the most valuable commodities in the post-first world war fur trade were Karakul lamb furs. Flocks grazed in the pastures of central Asia and northern Afghanistan.

As Afghanistan’s foreign reserves came increasingly to depend upon this trade, the government sought a monopoly from the 1930s. Jewish merchants were barred from travelling to the settlements in the north of the country, where they had long conducted business.

In this increasingly antisemitic environment, Jews in Afghanistan, including those who had fled there from Soviet central Asia, became impoverished.

The wealthier, including Hafaiz, left. Some joined relatives in the Bukharian quarter of Jerusalem. Jerusalem offered few trade opportunities however and many moved further afield, establishing new offices for family firms in London, Paris, New York, Montreal and Berlin.

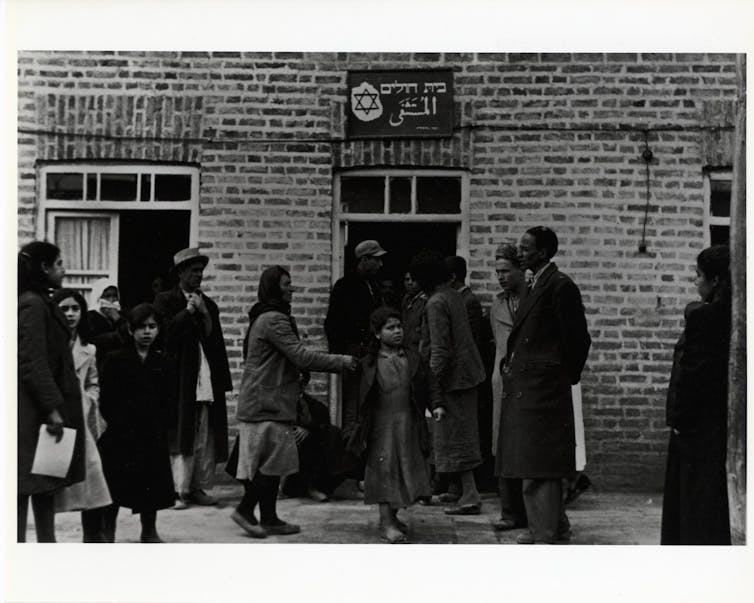

A lively Bukharian community in London was subsequently established. The son of one merchant told me he remembered his parents regularly playing cards with other families. In the 1930s, the Association of Bukharian Jews was established in the City of London, providing financial support to Jewish refugees from central Asia living in Iran, India and Afghanistan. It also raised the plight of Afghan Jews in Kabul with British officials in India and London.

After 1945, the UK government worked hard to re-establish London’s status within the fur, carpet and precious stones trades. It was eager to capitalise on the foreign currency that traders could earn through re-exporting their wares to buyers in the US and Europe.

By the late 1940s, Bukharian families had inaugurated a synagogue in Amhurst Park, north London. The daughter of a founding member of the community told me the congregation met in a small house: “Sometime in the mid-1950s I remember being given a gift of sweets on the occasion of the festival of Purim.”

Close Jewish-Muslim ties

These Jewish merchants maintained decades-long connections with Afghan officials and counterparts, who would visit with them in London. “I remember watching with amazement as my father ate the central Asian dish of plov [rice steamed with meat, sesame oil, cumin and carrots] while sitting in the traditional manner around a cloth placed on the floor with a Muslim from Afghanistan,” the son of a merchant from Samarkand told me.

In his 2011 memoir, Rumi Tomato, Muhammad Khan Jalallar, who served as minister of finance in Afghanistan in the early 1970s, recalls how merchants frequently travelled to Kabul and Peshawar. He mentions being visited by several Jewish “friends”, including “a chap by the name of Gabriel, who was a trader dealing in imports, working under another trader’s license”.

Jewish merchants also established close ties to Muslim intermediaries in Pakistan, who completed customs procedures for shipments to the UK. The daughter of a fur merchant in London told me that her father was friends with a “Muslim from Multan”. Her husband too remembered the Multani trader, who in turn invited them to Pakistan. “He told us we would be treated like kings,” he said, “because his family held ours in such high respect”.

Until the 1980s, Kabul was home to a small but lively Jewish community, approximately 700 people strong. My research shows they led a rich social life, picnicking in the mountains and dining in the city’s restaurants.

This ended with the Russian invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. Most Jewish families departed because of insecurity and economic collapse. Only a few men remained. London-based carpet merchants from Afghanistan sent items for Jewish rites to their co-religionists in Kabul.

One Muslim carpet dealer I interviewed in London, who travelled regularly between the UK and Afghanistan in the 1990s, said:

During the first period of government of the Taliban [1996-2001], a Jewish carpet dealer from Afghanistan in London who was my friend asked me to take matzah bread and kosher wine to the remaining Jewish men in Kabul. I was happy to take the bread, but told him I couldn’t risk travelling in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan with a bottle of wine, even if it didn’t contain any alcohol.

From the 1960s, increasing hostility in the west toward the fur trade led to its demise. Traders in London shifted to gemstones and diamonds. Others dealt in carpets designed with central Asian motifs and woven in Afghanistan. Some families left the city altogether, to join relatives in the US and Israel.

Those who remained mostly encouraged their children to focus on getting a good education. A merchant’s son told me that all he knew of his father’s trading activities was that he “did his calculations on the back of envelopes”. As a result, the institutions established in the early 20th century have largely been forgotten.

Central Asian heritage continuess to inform this community’s cultural life. People visit Uzbekistan and Tajikistan to identify ancestral graves. Their rich culinary traditions – as is evident in cookbooks including Miriam’s Table by London-based author Lilian Cordell – actively preserve the community’s past.

This hidden history of connection and commerce between Britain, Afghanistan, and central Asia serves as a reminder of the possibility of inter-religious coexistence in even the most fraught of times.

![]()

Magnus Marsden receives funding from the AHRC and Research England.