Seven aid workers from the food aid charity World Central Kitchen were killed in Gaza on Monday night when their convoy was attacked in a confirmed Israeli drone strike. This puts the death toll among humanitarians at over 200. Most of them have been Palestinians. Gaza is the most dangerous place in the world to be an aid worker.

It is also the most dangerous place to be a civilian. Delivering, as well as receiving humanitarian assistance can be deadly. In February, Israeli soldiers fired into a crowd gathered to collect flour, killing over 100 in what has been dubbed the “flour massacre”.

Humanitarian aid workers and people receiving aid should be protected and not targeted. Even wars have rules. The safe access of humanitarian relief to civilians in need is covered by the fourth Geneva convention. Despite this, attacks on aid workers in conflict areas are becoming more frequent around the world.

The safety and freedom of movement of humanitarian workers is essential to allow aid to reach those in need. In practice, this is implemented via what is known as “deconfliction”, where organisations provide armed forces with location details and movement plans of workers, as well as real-time communication during humanitarian operations to ensure their safety.

World Central Kitchen were reportedly coordinating their movements with the Israeli Defense Forces and their route had been pre-approved. Aid workers have since pushed for improvements to the deconfliction system, including improved lines of communication and “command and control” within the Israeli military.

Suspended operations

World Central Kitchen suspended its operations in Gaza after the attack. The seven staff members had unloaded 100 tonnes of aid from a ship before they were killed.

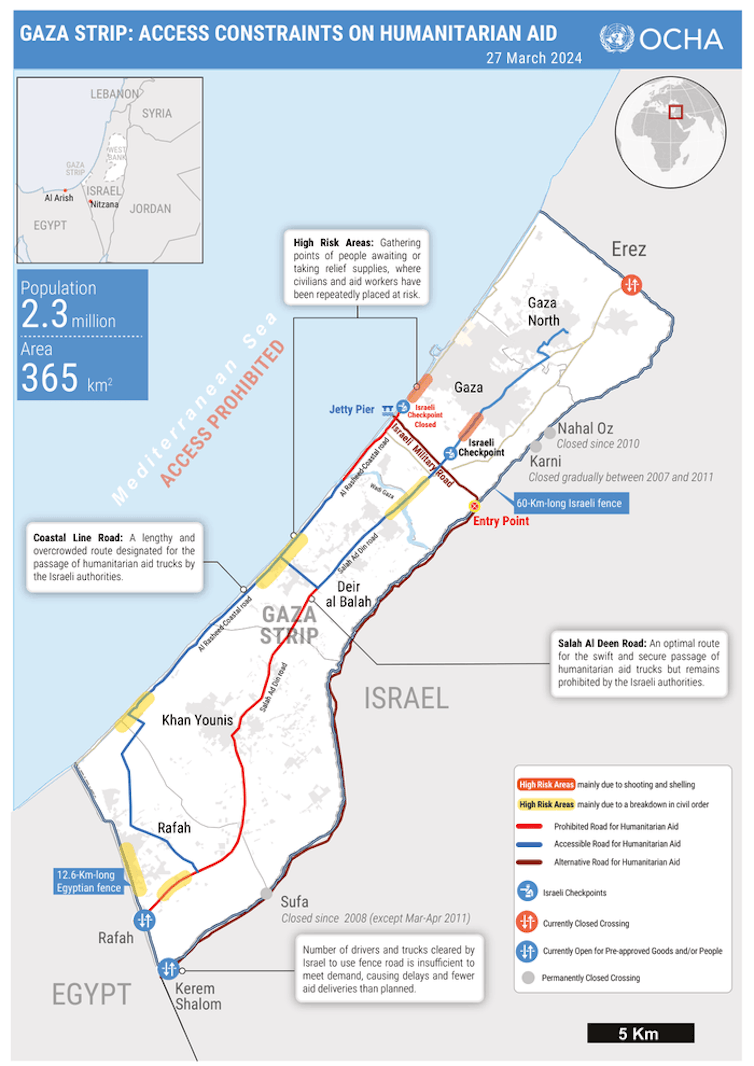

World Central Kitchen pioneered this maritime logistics corridor from Cyprus to a jetty south of Gaza City as road access to the Gaza Strip has been severely limited by Israel, despite growing fears of starvation. Another World Central Kitchen ship returned to Cyprus after the attack without being unloaded. For now, aid by sea is suspended.

UN organisations, which provide around 80% of the aid in Gaza, have suspended night-time operations in response to the attack. Several humanitarian organisations have paused their operations altogether as conditions have become too dangerous for their staff. Others are reevaluating their processes.

This is worrying, as UN experts have warned that widespread famine is expected in Gaza. Charity Oxfam has said people in the north of the Strip have been trying to survive on 245 calories per day – less than that provided by a can of beans.

Israeli authorities severely restrict the ability of humanitarian organisations to reach people in need in the Gaza Strip. Humanitarian aid currently enters only through two crossings (Rafah and Kerem Shalom) in the south. Movement of aid to Gaza’s northern region has been particularly difficult, prompting efforts to deliver aid by sea or air drops.

Air drops, expensive and operationally difficult, are seen as a last resort. In March, a failed parachute resulted in a dropped pallet of aid killing five people in Gaza.

In another incident, at least 12 people drowned trying to retrieve items that fell into the sea. Fights have broken out for the goods dropped in this way as there is no organised delivery on the ground.

Bringing aid into Gaza by ship is more efficient. World Central Kitchen’s first vessel carried around 200 tonnes of food, around ten times as much as a C-130 aircraft typically used for air drops can carry. But the problem of distributing the supplies around the Gaza Strip remains.

Need for humanitarian access

Safe and unhindered access for humanitarian goods and workers is vital for the survival of so many in Gaza. As an occupying power in Gaza, Israel is legally responsible under article 55 of the fourth Geneva convention for “ensuring the food and medical supplies of the population” by bringing “in the necessary foodstuffs, medical stores and other articles if the resources of the occupied territory are inadequate”.

Israel has banned the UN’s Palestinian refugee agency UNRWA from delivering aid to northern Gaza over allegations that some UNRWA staff took part in the October 7 Hamas attack. UNRWA has refuted the claims. Australia, Canada, the EU and others have since reinstated funding for UNRWA that they initially suspended. But some other countries, including the UK and US have yet to reinstate their funding. As UNRWA is the largest humanitarian agency with 13,000 staff in Gaza, this hinders relief operations significantly.

In March, a daily average of 161 aid trucks have crossed into Gaza per day, around three-quarters of which have carried food. This remains well below the operational capacity of both border crossings and the target of 500 trucks per day.

There is currently more than 280,000 tonnes of aid goods ready to be moved into Gaza according to the global Logistics Cluster, a humanitarian coordination mechanism led by the World Food Programme. More than 1,300 UN and NGO trucks have been verified and are ready to move into Gaza from El Arish in Egypt. The bottlenecks are the border crossings and lengthy processes involved in checking trucks and cargo.

Israel has been accused of deliberately using bureaucracy to obstruct aid supplies to Gaza.

In January, the International Court of Justice ordered Israel to take action to prevent acts of genocide, but stopped short of calling for an immediate ceasefire. In March, the UN security council passed a resolution calling for an immediate ceasefire. Ultimately, a ceasefire is the only way to ensure aid can enter Gaza at scale and be distributed to those in need safely.

The attack on the World Central Kitchen convoy has sparked global outrage. UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres said “it demonstrates yet again the urgent need for an immediate humanitarian ceasefire, the unconditional release of all hostages, and the expansion of humanitarian aid into Gaza”.

After 33,000 deaths in Gaza, maybe the deaths of six foreign humanitarians will finally trigger a more concerted global effort to reach a ceasefire deal.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.