The camel may be the next cow.

An animal that once grazed and browsed over huge distances is increasingly being enclosed in vast Middle Eastern dairy farms, where thousands of camels are milked by machine. This is the model of sedentary farming that produced modern cows, sheep and pigs. Camels have so far resisted it – yet in certain ways, they are ideal livestock for the next climate reality.

Camels evolved to cope with very hot days and freezing cold desert nights. They can go for days with little water or vegetation, and produce less methane than cows, sheep and other ruminants.

These traits make camels uniquely resilient to climate change, and mean they can play a key role in adapting food production as the climate changes, especially in deserts and other drylands.

But the same traits that make camels well-adapted to climate change also make them increasingly attractive targets for intensive farming. With big business interests hungry for ways to combine climate fixes and capitalist growth opportunities, an industrial camel industry is growing.

We have spent many years working with mobile camel herders in rural Arabia and Central Asia. We fear that a switch to industrialised camel farming will not only be bad for the environment, but will also mean crucial traditional knowledge and intangible cultural heritage is lost. It would be a shame if these “ships of the desert” end up as livestock stuck in a small paddock.

Growing demand for camel milk

The trend is driven by burgeoning demand for camel milk as an alternative to cow, sheep and goat milk. Camel milk is high in vitamin C when fresh, and also low in fat.

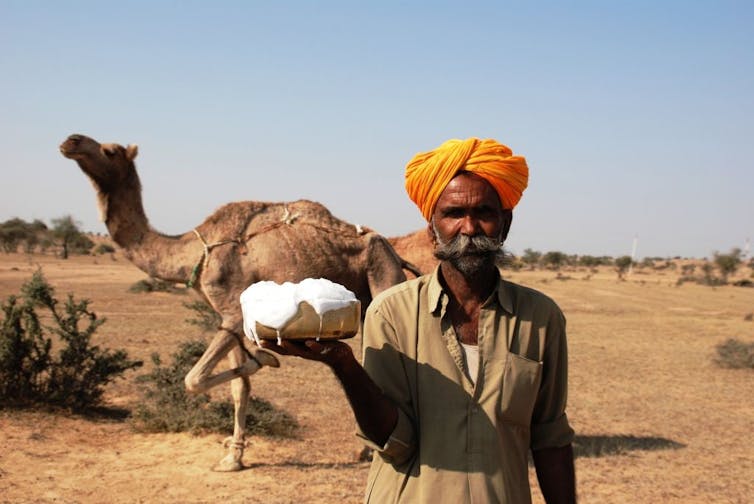

In the Gobi Desert of Mongolia and the deserts of Oman where we work, camel milk is consumed fresh and in milky tea. It is also produced as a fermented drink, or turned into a dried hardened curd for longer storage life. And we can attest to the unexpected strength of the distilled camel milk we tried in Mongolia!

Fresh milk produced by camel herders has a mild flavour which is often slightly sweeter in particular seasons, depending on the vegetation that the camels are grazing on. While herders in arid regions have always consumed camel milk, its new marketability rests on its mild flavour, lower levels of lactose and nutrient profile.

The increasing demand for both fresh and powdered camel milk is exemplified by the rise in small dairies in the least expected places, such as an Amish-Saudi collaboration in the US. All this is driving some capitalist entrepreneurs towards developing camel breeds that give higher yields of milk – much like domesticated dairy cows can produce far more milk than their wild ancestors.

Huge camel dairy farms

In the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia, camel dairy farms have been set up with thousands of camels – the largest, in the UAE, has more than 10,000 – including fattening units for male camels to be sold off for meat. More are being built, and in early 2024, the Saudi sovereign wealth fund announced further investment.

There are some challenges with raising camels on an industrial scale. Males tend to become very aggressive and even dangerous to humans during rutting season, while females have a longer gestation period than cows.

Nonetheless, the industry is expected to grow rapidly, with estimates for the future value of the global camel milk market ranging from US$2 billion to $13 billion (£10 billion) by the end of the decade.

In Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Oman, camels have become symbols of cultural heritage. Races and “beauty contests” can bring in astronomical prizes as high as £2 million. With such extraordinary rewards, it is not surprising that cloning and other advanced reproductive techniques have become more common in the drive to breed a winning camel.

Traditional camel herders are concerned

We’ve worked with nomadic camel herders in rural Mongolia and in the deserts of Arabia, where camels live without fencing restrictions and are milked by hand. Herders there are concerned about the shift towards mega-dairies, where milk is produced on an industrial scale.

International camel herder participants who gathered at one recent workshop in Rajasthan, India, released a statement saying they reject the “extractive model of animal production that was first superimposed on many camelid countries in colonial times”. They are wary of adopting a model for industrialised camel keeping that is “dependent on fossil fuels, chemical inputs and imported feed”.

Humans have worked with camels throughout history. Camels enabled long-distance trade, served in armies, carried military equipment, sustained family livelihoods, and contributed to early industrialisation. Today they are the face of many tourist brochures.

The emerging trend of industrialised camel farming, based on maximising milk production through enclosure and control of mobility, should cause us to pause and reflect. We are wary of what all this means for nomadic camel herders who produce fine wool fibre, milk, diverse dairy products and meat, using centuries-old animal husbandry knowledge and customs.

![]()

Ariell Ahearn receives funding from the ESRC and she is the Chair of the Commission on Nomadic Peoples of the IUAES.

Dawn Chatty has previously received funding from ECOSOC to set up a project to deliver government services to the camel herders of Oman.