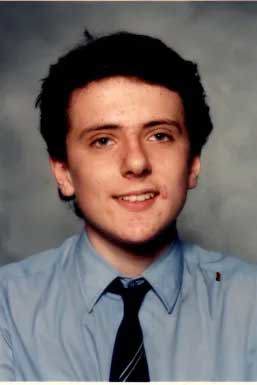

As a Sydney schoolboy in the 1980s, Charles MacKenzie was given donated blood as part of his treatment for a rare blood disorder.

The teenager and his family had no idea that the blood came from an ex-prisoner who used heroin, speed and cocaine.

MacKenzie, who is now aged in his 50s, became one of thousands of Australians infected with hepatitis C through donor blood. Others were infected with the HIV virus. Many of the victims had haemophilia, a blood clotting disorder, and relied on regular blood donations.

READ MORE: Britain slammed in inquiry for infecting thousands with tainted blood and covering up the scandal

For decades, MacKenzie – who runs the advocacy group Infected Blood Australia – has battled for justice on behalf of Australians who were given transfusions of diseased blood between the 1970s and early 1990s.

Now, the newly-released findings of a damning and extensive inquiry into infected blood donations in the UK has given MacKenzie and the dwindling number of other surviving Australian victims hope that they will finally receive recognition and compensation for their plight here.

The four-year British inquiry found the country's public health service knowingly exposed tens of thousands of patients to deadly infections through diseased blood and blood products, and hid the truth about the disaster for decades.

In an apology to victims, British PM Rishi Sunak said the inquiry's final report, released on Monday, "should shake our nation to its core".

MacKenzie said Australia needed to hold a royal commission into its own blood tainting scandal, which mirrored almost exactly what had happened in the UK.

"This has opened up the biggest scandals that's been buried for some people for 50 years and, from Australia's standpoint, we're the worst in the world," MacKenzie said.

"We need to focus on that. No-one was worse than Australia when it came to tainted blood."

Despite publicly leading campaigns for Australian tainted blood victims for decades, MacKenzie only shared his personal story for the first time when he testified at the UK inquiry in 2020.

He said he was moved to speak out about what happened to him because it felt like "this is our last chance".

"Before I die, and I'm an ill man, I want to know that I gave this every chance," MacKenzie said.

"So if it meant me sacrificing my rights and privacy, then I was happy to do this for Australia."

MacKenzie said he only found out about his blood donor's history when his lawyer obtained documents through the discovery process in 1997.

The documents included the transcript of a "lookback" interview the Australian Red Cross Blood Service conducted with the donor several years earlier.

They showed the donor had hepatitis C, used intravenous drugs and shared needles between 1974 and 1985. The donor had also spent time in prison and a prostitute was among his previous sexual partners.

"Rather than immediately contacting all of that man's previous recipients of his tainted blood, including me, they didn't. They didn't contact anybody," MacKenzie said.

MacKenzie said he had seen people die, and families have their lives ruined because of infected blood donations.

"We've got people who have lost everything, they've lost multimillion-dollar homes," he said.

"We have people that ran businesses that were active taxpayers, and they had no idea that they'd been infected by these treatments.

"And the next thing you know, they've got AIDS or hep C and they're in public housing."

MacKenzie's tireless advocacy efforts led to a Senate inquiry being held into "Hepatitis C and the blood supply in Australia" back in 2004.

The inquiry heard Australian Red Cross Blood Service estimates that between 3500 and 8000 Australians were living with hepatitis C derived through blood transfusions, including around 1350 haemophiliacs.

The inquiry's final report did not recommend a national compensation scheme for victims, finding it was not in their best interests.

Instead, it recommended the establishment of a body to deliver targeted financial assistance to victims.

However, McKenzie said the promised financial help for medical expenses never eventuated.

"There were a host of life-saving recommendations, they were going to pay for out-of-pocket expenses … not one cent was provided," MacKenzie said.

"They promised dental care, because so many people with HIV and hep C have bad teeth. Well, of course, that wasn't provided. I myself had to do a GoFundMe to get a tooth removed."

MacKenzie said the only apology offered was a qualified one spoken in mediation as the inquiry drew to a close.

In the inquiry's final report, an apology made on behalf of the Australian Red Cross Blood Service by Dr Brenton Wylie during the mediation meeting was noted.

"The Red Cross has recognised that, in the past, some blood-transfusion recipients contracted hepatitis C virus from blood transfusions," Wylie was recorded as saying.

"This is a terrible fact and we are sorry that this occurred.

"We are sorry that for some of those recipients contracting hepatitis C has resulted in often debilitating physical symptoms of this disease, and in some cases, unfair discrimination. We as individuals at the ARCBS have been distressed to hear of people's particular situations."

A spokesperson for Australia's Department of Health said the 2004 Senate inquiry committee found the most effective way to assist people who acquired hepatitis C through donated blood was to improve access to services and education of medical personnel, and to support research efforts to develop treatments for hepatitis C.

The Australian Government contributed to state and territory administered Hepatitis C Settlement Schemes, and provided $7 billion in subsidised access to curative direct acting antiviral medicines for all eligible Australians with hepatitis C, through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), the spokesperson said.

The Haemophilia Foundation Australia said on its website that while the government did contribute to settlement schemes for people infected with hepatitis C through tainted blood, stringent eligibility criteria meant "nearly all people with bleeding disorders were excluded".

MacKenzie said intervention and financial help for Australian victims was desperately needed.

In the UK, authorities are expected to announce compensation of about $19 billion in all to victims.

Interim payments of $400,000 to "living infected beneficiaries will be made within 90 days, the British government has said.

Compensation schemes for victims have already been set up in other countries, including Scotland, Ireland and Canada.

MacKenzie said it was bittersweet for Australian victims watching the progress made in the UK.

"Here in Australia, we see the Infected Blood Inquiry as if we are peering over a fence watching our British friends being liberated while we remain in a state of grief, barely surviving under the exact same public health scandal," he told the UK inquiry as part of his testimony.

"Thousands of Australians have acquired deadly hepatitis C and HIV from blood transfusions and blood products. What happened to victims and their families in the UK also happened to victims here."

A spokesperson for Australian Red Cross Lifeblood said: "We know the UK inquiry will remind people of a similar time that has had a long-lasting impact on many families in Australia and in countries around the world."

"We understand the pain it has caused, and our thoughts are with those affected and their loved ones."

Australia implemented a hepatitis C test as soon as it was available, the spokesperson said.

"Because of the Lookback program and the time that has passed since we started testing, most people who received a blood product in the risk years in Australia have been followed up or diagnosed."

Contact reporter Emily McPherson at [email protected]