Miltary spending is surging in the face of heightened geopolitical tensions. The UK plans to hike it to 2.5% of GDP by 2030, amounting to £87 billion a year. This is an increase from around 2.3% today, which Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has said is necessary in an “increasingly dangerous” world.

It comes at the same time as the US has signed off on a US$95 billion (£76 billion) military aid package for Ukraine, Israel and Taiwan. Meanwhile, the once dovish Germans want to become Nato’s leaders in Europe, and nations like France and Sweden are also pushing for increased military commitments.

We asked Keith Hartley, a defence specialist and emeritus professor of economics at the University of York, to offer his views on how defence will change in the years to come.

What will spending increases mean overall?

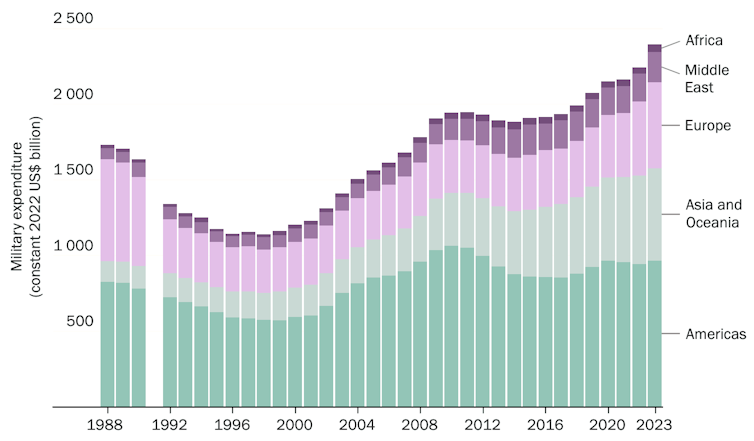

You’re going to see a general increase in the demand for equipment. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (Sipri), world military spending grew 7% in real terms in 2023, rising for the ninth consecutive year. This looks very likely to continue, not least because it takes time to ramp up production.

Global military spend 2008-23

You can’t just turn on the tap and produce far more Eurofighters than you have been planning. Look at what happened in the run-up to the second world war. The UK built thousands of Hurricanes, Spitfires, Lancasters and Halifaxes, but it meant increased labour, new factories and shadow factories (meaning units converted from other kinds of production). This programme dated back to the mid-1930s.

What kinds of change are we going to see?

An important change relates to the equipment that militaries will use in future. On the one hand, we’re seeing the development of what are sometimes called Augustine weapons systems, referring to new generations of equipment that are more complex and hi-tech than existing ones.

These are named after Norman Augustine, the former CEO of Lockheed Martin, who wrote a book forecasting that costs would rise so much as military technology grew more complex that countries would eventually only be able to afford a single warship, a single tank and a single aircraft. This trend has been happening for some time. For example, it used to be the case that Britain’s Royal Air Force bought 1,000 Hunter aircraft; now it’s relying on fewer than 150 Eurofighter Typhoons.

At the same time, you’ve got the development of very cheap but quite capable drones. For example, you can have a drone that goes out to sea and does aerial reconnaissance surveillance, staying there for hours without a manned crew. And while we think of drones as machines in the air, that’s going to change too. We’re going to see unmanned submarines, for instance, as well as drones in space.

So, one big question is to what extent we’ll rely on Augustine systems, and to what extent drones. Rather than highly expensive Eurofighters, we might have to make do with drones much more in future.

How would this affect the defence industry?

We’re moving to a situation where companies won’t be able to sell enough Augustine systems, so they’ll increasingly be looking towards international mergers to make the business viable.

At the moment, Europe is developing two different advanced combat aircraft to replace Eurofighter Typhoons. France, Germany and Spain are developing one known as the Future Combat Air System (FCAS), while Britain, Japan and Italy are producing a rival called the Tempest.

It’s going to be very costly for those nations to produce these similar combat aircraft, and countries won’t be able to afford them in large numbers. Typhoons cost about £100 million per aircraft, but the Tempest could cost five times that. So there’s every incentive for these buying countries to combine their orders, by merging their principal defence companies, to get a decent production run and share production costs.

It’s therefore likely we’ll continue the trend of a smaller number of bigger defence firms. For instance, Britain’s aerospace industry is dominated by BAE Systems and Rolls-Royce. I increasingly see those firms merging with, say, Airbus, or moving in an American direction and merging with a Boeing or a Lockheed. This means that you will increasingly see foreign firms playing a larger role in national defence, both in the UK and elsewhere.

Would national governments tolerate that?

It will certainly be interesting. In the early 2010s, BAE was going to merge with Airbus owner EADS (the European Aeronautic Defence and Space Company), but the German government opposed it.

Clearly, governments would have a worry about foreign takeovers in future – but they haven’t got much choice, frankly. The French seem to believe thou shalt not buy weapons from foreign companies, but they have got a limited budget. Similarly, Sweden used to pride itself on having an independent defence industry, but can’t afford it now.

With BAE or Rolls-Royce, I’d hesitate about them being the senior partner in a merger if it’s a US deal. The US would want to lead – and they’ve got the market to be the leader. I’m not sure how you get around that.

Similarly, I think we’ll see more cooperation between national militaries. France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, has been talking recently about a more integrated European military, which makes sense because national markets in Europe and indeed Britain are so small. But I do despair of Europe ever getting its act together.

Where is UK defence spending heading?

Both the main UK parties seem committed to 2.5% defence spending as a proportion of GDP. If that’s the commitment but the cost of Augustine systems is going through the roof, you’ll be paying more for less. It’s similar to the situation in the NHS.

But I do think it will happen, particularly if there’s pressure from people like Donald Trump (who wants Europe to contribute more to Nato’s defence costs). But it’s going to be at the expense of civil goods and services. It’s a classic case of guns v butter, Tridents v the health service.

![]()

Keith Hartley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.