If Israel’s ongoing assault on Rafah on the Gaza Strip is anything to go on, the concept of “red lines”, so beloved of US presidents as a measure of when to take action, is increasingly flexible. Back in February, when the Israeli government was planning the operation, the US president Joe Biden said it would have “consequences”.

An all-out assault on the area, where an estimated 400,000 people remain stranded for want of any other safe areas, would force the White House to reconsider its military support for its longtime close ally. Biden told CNN that if the Israel Defense Forces moved into Rafah, “I’m not supplying the weapons”. He reiterated that message on March 9.

But now the message coming out of Washington and Jerusalem is that neither Israel’s ground assault of Rafah which is well under way nor the Israeli airstrike which struck a tent encampment in Rafah, killing 45 people including women and children at the weekend had breached any red lines. Israel says it has gradually moved through the various districts of Rafah, relocating civilians as it has proceeded and always targeting Hamas fighters. And this means it has been a “limited operation”.

This hasn’t prevented the horrified reaction from much of the rest of the world at the images of the burned bodies of women and children from the weekend airstrike. The strike came just two days after the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ordered Israel to halt its operations in Rafah. The ICJ also ordered Israel to open the border crossing between Gaza and Egypt to allow aid to access a population that remains on the brink of starvation. But the ICJ has no power to enforce its rulings.

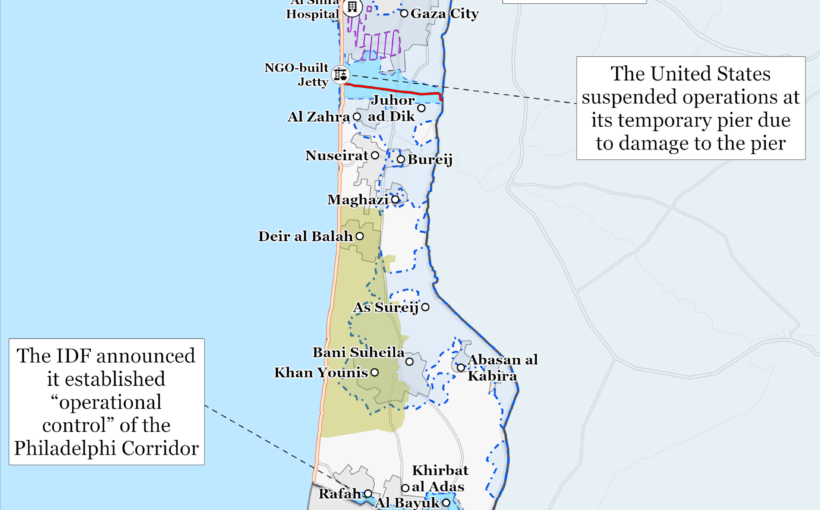

Now that the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) has total control of the Philadelphi Corridor, the 14km demilitarised strip which runs along the border with Egypt, opening the crossing should notionally be easy. But the latest reports are that it remains closed.

The ICJ ruling in turn came two days after the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), Karim Khan KC, revealed he had applied for arrest warrants for Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s defence minister Yoav Gallant, and several of Hamas’s top leaders on the grounds of war crimes.

These recent events suggest there has been a considerable shift in international sentiment away from hitherto fairly solid support for Israel, observes Julie Norman, a senior associate fellow on the Middle East at the Royal United Services Institute and an expert in international and US affairs at UCL. This will add to the pressure on both Netanyahu and the US president, whose longstanding support for Israel has been sorely tested over the past months.

But Norman believes this is more likely to result in a circling of the wagons in both Jerusalem and Washington. The White House described the ICC’s decision to seek arrest warrants for Netanyahu and Gallant as “outrageous”. It was reported that the administration was looking at the option of imposing sanctions on the ICC, which it doesn’t recognise and hasn’t ratified.

A lot, says Norman, is likely to hinge on the aid situation. Both the ICJ and the ICC rulings made a great deal of the need to increase the flow of aid into the Gaza Strip – and all indications are that, if anything, the reverse is true. Far fewer aid deliveries are getting into Gaza since the Rafah operation began in earnest and the news that the US-built pier off the Gaza shoreline has been knocked out of action by heavy seas prompted a group of humanitarian groups, led by Amnesty International, the Norwegian Refugee Council, and Doctors Without Borders, to declare that “the humanitarian response is in reality on the verge of collapse”.

Assuming for the moment that the ICC does issue arrest warrants for the senior Israeli and Hamas leadership (something condemned by critics as creating a “false equivalence” between the two countries), what then? Majbritt Lyck-Bowen, an expert in reconciliation and peacebuilding at the University of Winchester, believes that the ICC may be the only route to justice.

Lyck-Bowen draws parallels with the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY), which was established by the UN to prosecute war crimes committed during the Yugoslav wars (1991–2001). One of the main criticisms of the ICTY was that its operations could jeopardise negotiations towards a peace deal. In the end, it wasn’t until quite some time after hostilities ceased in the Balkans that the first arrests were made. But it did net some big fish, including Bosnian Serb leaders Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić for their roles in the Srebrenica genocide.

While considering this issue, it’s important to note that the ICC and the ICJ are entirely separate legal instruments with distinctly different powers and jurisdictions. International legal experts Avidan Kent, Kirsten McConnachie and Rishi Gulati of the University of East Anglia explain.

Palestinian statehood

Into the middle of all this came the bombshell news on 24 May that Norway, Ireland and Spain would recognise Palestinian statehood, something they proceeded to do on May 28. This brings the total number of countries recognising the state of Palestine to 143.

Lancaster University’s Simon Mabon has been watching and publishing on Middle East politics for many years. He answered our questions on the implications of this decision and what Palestinian statehood might mean for peace in the region.

Among the important issues Mabon raises are how this might fit with a peace deal and eventual two-state solution. Many of the hold-outs on recognising Palestinian statehood fear that doing so prematurely might undermine the Oslo Accords, which laid some of the groundwork for a two-state solution. And yet the conundrum is that a two-state solution would also require the establishment of a sovereign Palestinian state.

We were also keen to know what sort of a foreign policy a newly established state of Palestine might pursue. As Mabon points out, sovereignty means just that – Palestine’s right to establish its own security arrangements and alliances, whatever that might mean and regardless of what the US and Israel might want.

Another important point about the recognition of Palestine by Norway, Ireland and Spain is that they are all European countries. Of the 140 nations which had previously recognised Palestinian statehood, few had been in Europe. This is changing and there is talk that Malta, Slovenia and Belgium might soon follow suit.

But if individual European countries have been slow to recognise Palestinian statehood, European institutions have been far more positive, write international relations scholars George Kyris of the University of Birmingham and Bruno Luciano of the Free University in Brussels, who walk us through where the EU stands on Palestinian statehood.

What Israelis think

Throughout the conflict, reports from Israel have been of the understandable hurt caused by the savagery of the Hamas attack on 7 October. As you’d expect, the focus for most of the Israeli public is to secure the release of the remaining live hostages and the restoration of the remains of those who have died to their families.

But this by no means translates into a blank cheque for Netanyahu. In fact, writes Arie Perliger of UMass Lowell in the US, the Israeli prime minister is deeply unpopular with his electorate who are desperate for new leadership. Perliger identifies what he calls the “Masada complex” named after the last stand of the ancient Kingdom of Israel against the Roman invaders in AD78, which saw the expulsion of the remaining Jews from the region and an end to Jewish self-determination for nearly 2,000 years.

As a result, says Perliger, security comes above all other considerations for Israelis. They just think that a different leader will be needed to ensure that security going forward.

And it’s not a zero-sum game. For many Israelis, peace and security doesn’t necessarily preclude Palestinian self-determination, writes Colin Irwin, a peace researcher with the University of Liverpool. Back in the 1990s Irwin was involved in the negotiations that led to the Good Friday Agreement. As a public pollster retained by Bill Clinton’s Northern Ireland envoy Bill Mitchell, Irwin gauged all shades of opinion from all sides of politics, publishing polls in local newspapers to ensure that negotiators had a full picture of red lines on all sides from which to build a workable peace settlement.

Irwin was retained again by Mitchell after the election of Barack Obama as US president in 2008, this time to work on a Middle East peace agreement. But having been given preliminary support from both Israel and Hamas, in early 2009 Netanyahu was elected to his first term as prime minister in Israel. His refusal to talk to Hamas effectively halted the process before it could start.

But Irwin has recently taken polling among both Israelis and Palestinians as to the practicality of a two-state solution and found that both sides are more amenable to the basic idea than the people of Northern Ireland were in the lead up to the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. He believes this is a sign that, with different leadership, a lasting peace is possible.

Taxing episode

What is unlikely to help smooth the way to a settlement is the announcement this week by Israel’s far-right finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich, that Israel will withhold Palestinian tax revenues from the Palestinian Authority (PA) in the West Bank “until further notice”.

This revenue makes up between 60% and 65% of the PA’s budget, write Shahzad Uddin of the University of Essex and Dalia Alazzeh of the University of the West of Scotland. The pair, both experts in public finances, note that Israel has used this tactic six times since the peace accords of the 1990s, when it began collecting tax on behalf of the Palestinian Authority.

They believe that Israel uses this mechanism as a form of collective punishment against the Palestinian people. It has harmed the wellbeing of the people, strangled the local economy and perpetuated their sense of siege. Yet another barrier in the way of a lasting peace.

![]()