Three hundred years ago, on June 5 1724, an Anglican clergyman by the name of Henry Sacheverell died in Highgate, north London. He was 50 years old.

Sacheverell’s death passed in relative obscurity. His home in The Grove in Highgate Village arguably remains better known as the site for several subsequent residents of great renown, from Samuel Taylor Coleridge (who lived there from 1823 until his death in 1834) to Kate Moss (from 2011 until 2022).

In his lifetime, however, Sacheverell gained significant notoriety for a seditious sermon he preached in 1709. It sparked violent riots, one of the 18th century’s largest free speech debates and a landmark parliamentary trial. It is the only one in English history to have both directed the course of English politics and initiated a roaring trade in celebrity merchandise.

My research looks at the cultural lives of clergymen in early modern England. Historian Greg Jenner has dubbed Sacheverell the earliest example of a celebrity.

Henry Sacheverell was born in Marlborough, Wiltshire in 1674. At the age of 15, he matriculated on a scholarship to Magdalen College, Oxford. After graduation, he served briefly as a vicar before returning to his alma mater to take up a fellowship.

As an Oxford don, Sacheverell was disliked by his colleagues for his arrogance and drunkenness. He developed a fiery and charismatic oratorical style.

A staunch Tory, in 1702, he published several campaigns against Whigs and Dissenters from the Anglican Church. The Tory Party at the time was unwavering in its support for the monarchy and the Church of England. The Whig Party, by contrast, was opposed to absolute rule. They fought against what they believed was the corruption of the English church and supported the Dissenters – Protestants who refused to conform to the Church of England.

On November 5 1709, at St Paul’s Cathedral, Sacheverell delivered his most provocative sermon to date.

By Anglican convention, November 5 sermons at the time commemorated the anniversary of the gunpowder plot on that day in 1605. As opportunities for thanksgiving, they would focus on God’s deliverance of the nation from Roman Catholicism and, traditionally, would also make reference to the providential landing of William of Orange in England on November 5 1688.

Sacheverell did no such thing. He described the gunpowder plot in sensationalist terms as “[a] Conspiracy … as only could be Hatch’d in the Cabinet-Council of Hell”.

He drew analogies between November 5 1605 and January 30 1649, the day on which Charles I was executed. To his mind, these two dates were “Indelible Monuments of the … Blood-thirstiness of both the Popish, and Fanatick Enemies of Our Church, and Government”.

He further attacked both the government and the Dissenters as “Factious, and Schismatical Imposters”. He accused those in power of engineering the ruin of the Anglican Church by “bring[ing] the Church into the Conventicle”, which constituted a “confused diversity of contradictious Opinion”.

The Whigs were outraged by Sacheverell’s invective against their policy of religious toleration. By a parliamentary majority, they promptly impeached him for misdemeanours against the state.

However, in doing so, they contributed unwittingly to the Tory cause. Sacheverell was made to play the role of sacrificial lamb on the altar of his faith and freedom of speech. Parliament found him guilty of sedition but handed him only a token penalty.

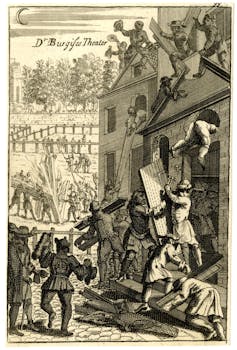

As the trial was taking place, riots took place in London (including at the Bank of England) and across the country. Over the course of several months in 1710, supporters of the Tories attacked the homes and meeting houses of Dissenters.

Though Sacheverell was found guilty, the trial robbed the government of credibility. The Tories won a landslide victory in the general election of 1710.

The celebrity cleric and his merchandise

Sacheverell was banned from preaching for three years. The sermon was ordered to be burnt – a performative gesture which, in reality, had no effect on its circulation.

The Perils of False Brethren reputedly sold 100,000 copies and was translated into French. Copies were made available to at least a quarter of a million people, the equivalent of the entire English electorate at the time.

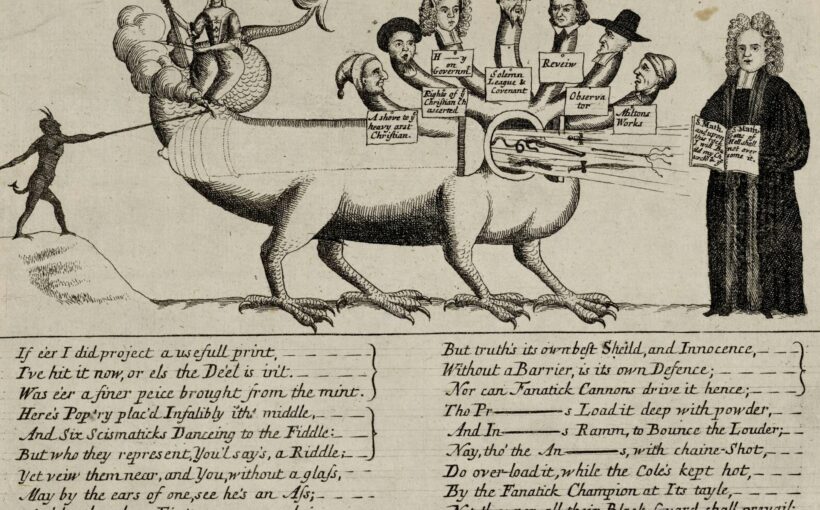

The popular press further swarmed with pamphlets and broadsides catering for an eager public fascinated with Sacheverell: the preacher, the man, and the criminal.

Single-sheet verses costing one penny, such as The Impeachment (1710), depicted Sacheverell as a “Nightingale” who was to be “cag’d for some Expressions past” and “adjudg’d, some Time to come, / To practice Silence”.

Another broadside, The Age of Mad-Folks, provided more general commentary on the consequences of what became known as “the Sacheverell Affair”. It mentioned people rioting and swearing to pull to the ground churches that “wanted a Steeple”; that is, the meeting houses of Dissenters, which, unlike traditional churches, did not generally have steeples.

Tory supporters, meanwhile, sang of their party’s victory. A 1710 broadsheet, entitled A New Ballad, To the Tune of the Black-Smith, closed with a gibe at both Houses of Parliament:

But, Nobles, take care, you rue not the Hour, / When the Commons were thus put in mind of their Power / Impeaching’s a thing that has made you look sour.

Another attributed the Tories’ success directly to Sacheverell: “Sacheverell we thank for the most happy Lott / Of having this Administration.”

Printers instantly seized upon the marketing opportunities this public appetite presented.

Tongue-in-cheek couplets at the bottom of engraved broadsides, solicited readers to buy copies of the sermon. As one, held in the British Museum, says:

What tho: this EMBLEM, may have little in’t, / Yet since you bought the Sermon, buy the Print.

Craftspeople produced souvenirs including portraits of the bewigged clergyman as diminutive ceramic figurines and painted in blue on tin-glazed earthenware dishes.

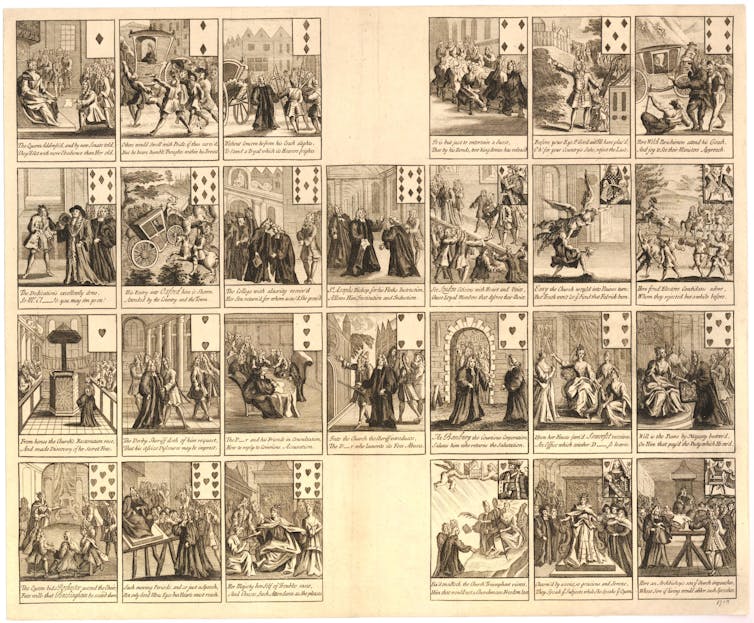

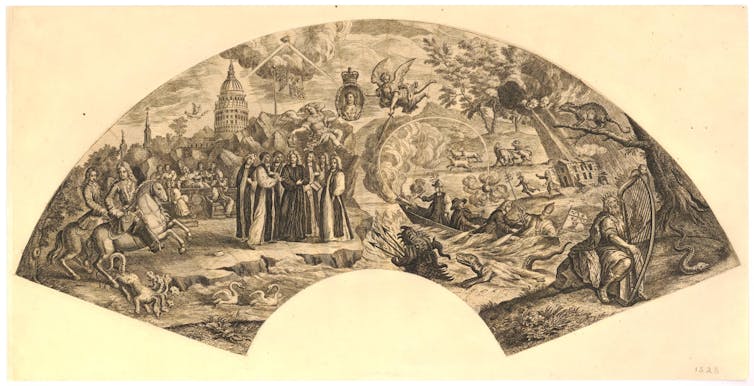

Allegorical scenes of “Doctor Sacheverell” being visited by angels while antagonists suffered retribution from God were emblazoned across delicate fans and stamped on to lead medals. Broadside ballads, satirical prints and sets of playing cards would further commemorate Sacheverell’s career for decades.

![]()

Hannah Yip receives funding from The Leverhulme Trust.