Polestar, now a more independent brand distinct from Volvo, is gearing up to deliver its most affordable cars yet.

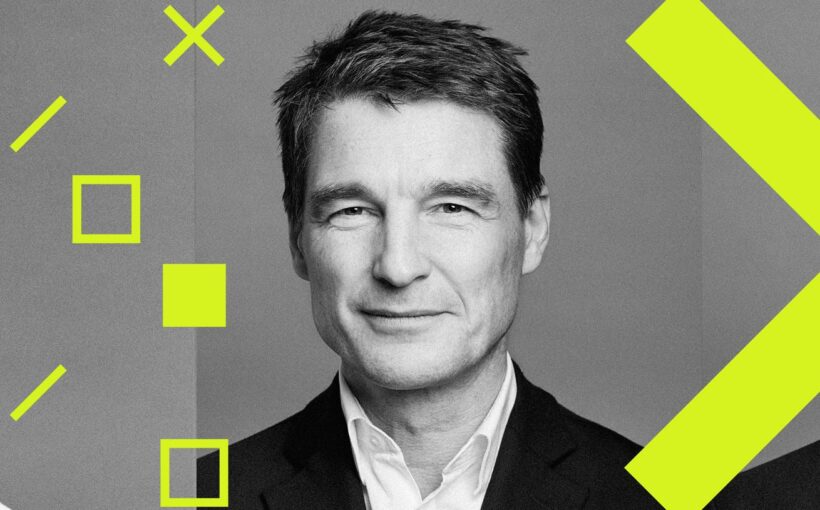

Today, I’m talking with Polestar CEO Thomas Ingenlath, who was first interviewed on the show back in 2021. Those were heady days — especially for upstart EV companies like Polestar, which seemed poised to capture what felt like infinite demand for electric cars. Now, in 2024, the market looks a lot different — and so does Polestar, which is no longer majority-owned by Volvo. Instead, Polestar is now a more independent sister company to Volvo, and both carmakers fall under Chinese parent company Geely.

You know I love a structure shuffle, so Thomas and I really got into it: What does it mean for Volvo to have stepped back, and how much can Polestar take from Geely’s various platforms while still remaining distinct from the other brands in the portfolio?

Thomas has a refreshingly candid perspective on why people prefer certain car brands — he thinks desirability is the number one factor for Polestar — and how his company thinks about its relationship to Volvo, other luxury carmakers, and the EV market in general.

And Polestar is trying to grab more of that market. The first time Thomas and I talked, Polestar’s only mainstream car was the well-reviewed Polestar 2. But this year, Polestar expects to start delivering its Polestar 3 SUV to customers and debut the crossover Polestar 4 — filling out the model lineup and hopefully competing for the attention of more car shoppers.

Of course, it wouldn’t be a Decoder car episode if we didn’t talk about the software experience in the car and how it’s changing. Unlike so many of the car execs I talk to, Thomas doesn’t see software as a big opportunity — Polestar cars today run the Android Automotive OS in partnership with Google, and in China, Polestar just partnered with Xingji Meizu, another Geely company, to use a platform called Flyme OS. You’ll hear Thomas talk about that partnership and where Polestar is comfortable ceding control to Apple, Google, and others.

Thomas is a designer, so I had to ask him about recent trends in car design, including the retrofuturistic shift we’re seeing from companies like Rivian and the more, shall we say, dystopian aesthetic of the Cybertruck. I have to say, Thomas has one of the best responses to the Cybertruck design I’ve heard from anyone in the industry.

Okay, Polestar CEO Thomas Ingenlath. Here we go.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Thomas Ingenlath, you are the CEO of Polestar. Welcome back to Decoder.

Hi, Nilay. Great to be back here.

I am very excited to talk to you again. Your first conversation with us in 2021 was a highlight. We had just started the show, and you were one of the first car CEOs to come on the show with us. You took a risk. Thank you so much. I look back on that episode fondly.

Yeah, and that seems like a long time ago now.

Chronologically, three years is a long time ago. But also, the whole car market has changed in those three years. A lot of things have happened, and the assumptions we were all making about the car market in 2021 have radically shifted. EV demand has changed. The demand for hybrids has gone back up. The competition has changed. Your big competitor, Tesla, has really changed, and Polestar itself has changed. I hope you’re ready for this conversation because we have to cover all of it.

Let’s start with Polestar itself. There are some fundamental structure changes I think will help me understand everything else. Decoder is fundamentally a show about structure. Polestar just went through some big structure changes. The last time you were on the show, the majority owner was Volvo. That’s changed. Volvo has stepped back. I think it has an 18 percent ownership stake now. Geely, the parent company of both Volvo and Polestar, is funding Polestar.

I have a quote from you from last time. This is one of the reasons I love that episode of the show because it’s such a good quote. I asked you to describe the relationship to Volvo, and you said, to paraphrase, “Volvo is our parent company, Polestar was born there. Volvo has raised its baby. It’s growing up and becoming an adult. We are in the process of moving out, earning our own money. We’ll always be some kind of family, but of course we will develop our own life.” That appears to have happened. You’ve moved out of Volvo. What is that relationship like now?

Well, it’s still a relationship. It’s still a family. You can do whatever you want. Once you’re family, you’re family. But you grow up and you move out and you become more independent. That happens in families. There are periods of bigger distance, periods when you find each other again.

Having said that, compared to how ’21 was laid out as a plan, it’s really not that much of a change. Let’s face it: the cars, for example, that are a testimony to that growing up were in development at that point in time. From a very early Polestar 1, even Polestar 2 — [when we] still had a tight relationship to Volvo — to the Polestar 3 and Polestar 4 — [when we were] growing more into an independent company — it was part of the long plan.

But I would love to point out what was not as visible in ‘21, and maybe it’s really different from where we find ourselves now in 2024. One element that we have been talking about a lot is how much innovation speed, relevant electric mobility, relevant technology, has accelerated momentum and dynamics within the Geely group in other brands where it is relevant for us to broaden our way of using the brand technology portfolio and hook up and do things on a broader range within the Geely group.

I think it’s reflecting what’s happening in the world. Let’s face it. China EVs did not become competitive or a threat to the OEMs of the world because of subsidies. They are technically competitive, highly competitive. That is what makes them a threat. We should be a little more honest about that and, for that reason, the advantage for us to hook up to that technology as a European OEM. I mean, Polestar is here in Sweden. It’s a very European company.

We are harvesting and using that technology as well to go forward. Volvo is reducing the ownership structure, but the 18 percent stake that they keep certainly is beyond whatever you would call a strategic partnership. That’s heavy involvement. That is a strong ownership still, and the relationship that we have in terms of producing cars together, developing technology together, is untouched for that reason. Any investor talking about Polestar, I always try to separate that. One thing is the ownership structure. The other thing is the technology and where we produce cars. That is different. We are on track to be much more of a global company, manufacturing footprint-wise.

All of that is much more on the move. We will gain with this reduction of ownership of Volvo from around 48 percent to 18 percent something in the long run very beneficial for Polestar, and that is to increase our free float. That was almost a promise when we listed the company, that that would be an effect, that the main owners would actually let go of some of the ownership in order to increase the free float and let other people participate in it. So, in a way, you can read it. We might have even talked about it in 2021. That was always the story. But turbulent times, of course. This is a world that is [seeing] a lot of developments.

We have seen the EV market, and that’s a strange thing. In ‘21, if we would’ve talked, we still had to actually talk about the conviction that EVs would be a technology. And then, funnily enough, we have seen within that time — ‘22, ‘23 — a big wave of electrification and all the OEMs suddenly saying, “Oh yeah, we will do it till year epsilon.” And now, within that short time, there’s a swing back again. You can see how fast these things are happening. Having witnessed that the last three years, I’m actually not that worried about talk today of, “Oh yeah, it’s now hybrids and let’s stick to the high-end cars.” That is going backward and forward so quickly.

I think the conviction that we have about the technical superiority of the electric drivetrain and the necessity to reduce CO2 will naturally [occur]. You have to focus on that long-term thing, and that is that electrification will then be able to be innovative and keep people actually interested in cars because that’s where the tech is happening. [Then, that allows you to] make progress on the journey of decarbonization.

You’ve hit on almost every single thing I want to talk about, so let’s take them in order. The thing you’re mentioning — the furious rush in 2020 and 2021 to electrification, all these announcements, and then the pullback — I definitely want to talk about that. With the financial climate back then with low interest rates and lots of free cash, people made very different kinds of decisions. That has obviously changed now.

But I want to stick with Volvo and Geely for one second. You mentioned something really interesting, which is that the Chinese EV market has not developed because of state subsidies from China and that there’s technical superiority in some of the products. Obviously, Geely is a Chinese company. I believe right now it’s passed BYD at least in some months for total EVs shipped in China and the world. That is a furious battle back and forth. What are you pulling from their platforms, from their technical developments, that gives you an edge in the markets here?

Well, there’s technology that we use. For example, we’re building the Polestar 4 on technology that is coming from the Geely group. There are elements like electronic architectures where we definitely can harvest things that are developed in the Geely group and that we take as the starting point. For example, for the Polestar 5 to then develop the electric architecture on the Polestar 5 on this basis.

That’s where the speed is here, the key point. It’s not necessarily just that there’s some genius element in it. It is how fast you can move things forward, how quickly you get to a product, and the openness to actually implement change and react to the demands and wishes that we have as a brand and to incorporate that. That’s really where we benefit in working with them. The windowless virtual rear window Polestar 4, it’s the first product where I think it becomes very tangible how that technology is a very good base for us to develop an amazing Polestar product on it that’s interesting for the consumer.

One thing I think about with all of the car conglomerates is there’s an element of brand segmentation within them and then there are some of them that are just in open competitive friction. I would say GM does a very good job of very crisply segmenting its brands. You buy a Cadillac at the top of the market; you buy a Chevy at the bottom. Hyundai and Kia seem to be locked in ferocious sibling rivalry, which I think is making them both better. How does that feel for you inside of Geely with Volvo? I want to point out: this is a radio show. Thomas is smiling. He smiled a lot when I asked that question. He’s still smiling.

You see, because it’s an interesting story there. We tend to always categorize it: “Oh yeah, there are these companies where there’s very clear structure and then there’s where you feel like, ‘Okay, are the borders a bit fluid?’” And yes, there might be that generalization you could apply. I worked in the Volkswagen group for a long time. For two decades, I was within the Volkswagen group when a lot of brands were bought. And it took, I call it now, German rationalism: this idea that you want to put it all in a box. There was a big effort to structure it, and to a high degree, it has been structured. There was a very clear brand and mission.

Having said that, was there not friction and discussion between the brands? Of course there was. You could see that between Volkswagen and Škoda. You could see it between Audi and Porsche. So even if you try to do that, there will be some kind of friction happening. I always try to explain that’s normal. That is the normal friction that you have in any well-functioning family. The question is: how much does that lead to a creative growth of the collective whole, or how much is that actually disturbing the development of the individual brands? And that’s, I think, the healthier parameter, whether that creates a positive creative dynamic for the group or it’s something that is actually destructive and much more than “are we all nicely boxed in in our segment?”

Let me give you some examples there. I would say the ferocious rivalry between Hyundai and Kia is working for them because they are putting out radically designed cars. They’re probably pushing forward more than any mass-market automaker. They make a lot of cars, but they are designing at the boundaries, which is cool. They’ve raised awareness of both brands, at least here in the United States, and they’re growing market share for both brands. That’s working for them. Is that sustainable? I don’t know.

It feels like you could enter into that kind of relationship with Volvo, which has a bunch of small EVs, and you could grow the total EV market share of Volvo and Polestar in the United States by just going at it. Or you could say, “This is how much market share we want for both, and we’re just going to move customers between them.” I don’t think anybody ever picks the second one, but more companies in this situation end up moving customers between them than actually growing the total number of customers. How do you avoid that outcome? Because it seems like the goal is to grow the total EV market share.

For me, it’s so clear. I’m convinced that we have a chance to significantly grow the reach and the group of customers that we address for a simple reason. Having been at Volvo, I would say successfully building a lineup of cars actually repositioned Volvo in that premium segment, but with very distinct branding, being so much about an inclusive brand. Actually, even people who don’t buy a Volvo are very positive, and you are never offending anybody with a Volvo. It’s a very inclusive, value-driven brand that is obviously centered on the original car of safety, developing that into modern autonomous driving safety. It’s very well positioned. But also, how much did I see that there are a lot of customers for a Mercedes AMG, for a sporty Audi, that we obviously cannot easily address now with a Volvo product? Because let’s face it, that needs a different profile of car, a different profile of attributes.

That’s actually one of the starting points now, talking as a designer, where I felt like, “Wow, this Scandinavian design world actually has a more techy and more sporty car, which we, at the moment, rightfully should not address with the Volvo brand.” So reaching out to say, “Come on, let’s create a new Scandinavian brand that is actually catered to capture those customers — a bit more provocative, a bit more controversial, [something that’s] not pleasing everybody.”

Daring to do a car that has no rear window but only a virtual mirror, that is something that you can do with a brand that is that much more controversial. Having a chassis that is that much more catered to the driver, where the kids in the second row might get a tiny bit more of a hump when they cross a speed bump. There are all these things that we can do now with Polestar in order to actually build that more driver-centric, more provocative, more power-driven experience. To be more “techy,” not old, warm, or comforting.

All the stuff, if we would have done it at Volvo, Håkan [Samuelsson] would’ve told me, “Oh, that’s too German, too techy, that’s too cold.” To do that in a techy way, that’s why I feel we positioned these two brands peacefully next to each other. I had that very clear statement recently: Polestar 3 parked next to a [Volvo] EX90. Both cars are very much on the same wheelbase and the same technology starting point, but [they are] so different in what they offer to the customer — even visually. I mean, if you don’t see and get the difference between Polestar and Volvo looking at these two products, then I can’t help you. I think we are on very healthy ground when it comes to brand differentiation.

Let me ask a couple more Decoder questions, and then I want to talk about the EV market and how it’s changed. Last time we spoke, you had about 1,000 people. Earlier this year, you did some cuts, about 15 percent. How big is Polestar now?

We are around 2,800 people. We are on the way to reach, by the end of this year, 2,500. That is the process that we are in.

And how is Polestar structured? How have you organized the company?

Well, there is a big part of our organization here in Gothenburg [Sweden] with the central sales department. We have the headquarters for marketing sitting here in the building. We have our quality and service. All of that is here. The R&D is partly here, but a big part of our R&D, especially the one that is taking care of the aluminum architecture that the Polestar 5 and 6 are built on, is located in the UK. The bigger portion of our R&D sits there in Coventry. I could almost say that’s it. But then, of course, we have 27 markets, and each market has what I call a small Polestar market lead there. I hope I didn’t forget anything. That’s about it. We have a few more of our quality people sitting next to the factories. That is something that we build up slowly with the car line growing.

But we take care mainly of what we call the attributes that make Polestar “Polestar,” and that’s our interface where the customer touches and feels a car. That’s all the feeling that you have driving a car. We really appreciate the car being a physical object, not just a digital device. So these two elements: a very traditional chassis department and a very modern, advanced, designer-driven digital interface. We do all the app development that we need in-house. So that’s the stuff that we take care of. Do we involve [advanced driver-assistance system] technology and develop the autonomous drive functionality of a highway pilot with hands-off technology? No, that’s technology that we harvest from the group.

So this is the key Decoder question. I love asking this question of former designers in particular because I get a lot of consultant-type CEOs. How do you make decisions? What is your process for making decisions? Even listening to you talk, it feels different than everybody else.

Indeed, my background makes me make decisions knowing that most decisions you have to make without really having the proof on the paper. Otherwise, it would be easy for anybody to make that decision. To a certain degree, you have to take that risk of projecting what is going to happen in the future. Where is consumer taste going? I had to learn as a designer to be very much on my own — with whatever data you try to prove it with.

But at the end of the day, it comes down to you making a judgment about where it is going. It is a very lonely decision when you make the proposal of which design to go with, and I think that’s a very tough but very good school to become serious about making a decision and being aware of the responsibility that you take on yourself by making a call. “Oh, it’s this or it’s that design,” and exactly like that, we have to make certain decisions when it comes to business models, when it comes to markets. You have to listen to a lot of stuff, but at the end of the day, it’s clear you can’t hide behind the rationale of a spreadsheet. You have to stand by the decision and be bold in making that lonely decision.

For a lot of reasons, Polestar is perceived as a brand with a very, very strong identity and a very strong appearance — wherever you see it, touch it, feel it. Of course, for me, the biggest value that we create with this company is the brand value. This is the long-lasting value that we create. Technology comes and goes, models come and go. In 100 years, what we will have created is the value of the brand. For that reason, when you ask me what the framework is for how I make my decisions, it’s how does the decision that I make now here — do we go with A or B? — how does it reflect on our brand? How does that affect how our brand is perceived?

It is, for me, a very important element of making sure people identify with something that they perceive as an incredible brand. Desirability will be key for the purchase decision of our products. It is not the bread-and-butter car; it is not the economics of the car that make you buy a Polestar. It is about the fascination and the desirability of the brand. That’s why a lot of the decisions that we make, we always have to think about, “How does that reflect on our brand?”

There’s a lot embedded in that statement. The desirability is why people buy cars. I don’t think it’s an unusual point of view for a car executive, but the conviction that you have in it is, I think, unusual. To have a brand for 100 years, you need to sell a lot of cars. The market for EVs in particular needs to exist and overtake the market for ICE vehicles.

This is what you were talking about earlier. There was a furious rush to announce EVs, to announce plans for all-EV lineups. It’s the consumers who didn’t go along with the plan. The demand did not increase at the rate that everybody had projected. Was that just pandemic, zero interest rate thinking that “We can see how expensive Teslas are and the infinite demand for Teslas, we can have a piece of that”? What did the car industry get wrong there?

I would very much disagree that the consumer didn’t go along [with that].

Well, the sales have not increased at the rate we expected. I can look at car lots around me. The EVs are sitting there.

Now we can just simply discuss, “Okay, what speed of increase [do you mean]?” The EV market is still growing. How fast is it growing? That’s a question. And again, it’s almost like a climate change denier saying, “Hey look, it has been raining for two days, so what do you expect? Why is everybody worried about the temperature on Earth increasing?” Just because you had one cold winter doesn’t prove that climate change doesn’t exist. So that projection on what will happen in 10 years, yes, I’m very convinced that the EV market will gain market share year after year after year just because I’m so convinced that it is that much more pleasant to experience a drive in an electric car. That is just purely from a product quality standpoint.

When I go back now and drive a combustion engine car, it is a disappointment because it feels like old technology. Then, rightfully, there is a question of how affordable EVs are. And, of course, companies like Tesla and BYD have now opened that door to actually make EVs affordable — not maybe to the extent that it has to still go, but the trend is there that you actually see that EVs have become very affordable. That is how Tesla moved away into a mass-market brand. That’s very different to what our ambition is. Now, for that reason, I may not say I’m relaxed, but I’m convinced that the EV market will grow and become the majority of the share between ICE cars and EVs.

Now, let’s presume for a second that I’m totally wrong and that will not happen. Would that actually matter for what we are after with the Polestar brand? I would say no because what we are now building and doing is a premium performance electric car brand, and even if the mass market stays on hybrid ICE cars, to me, it is so crystal clear that if you want to build a modern performance car, how would you do it other than electric? This technology is so much more powerful. It is a much greater prerequisite to actually building a high-performing car. That’s where I feel like, in that corner, you have such an amazing offer for the customer. Charging speed is relevant, but that’s increasing dramatically. Look at how the Polestar 3’s charging speed is actually much superior, just right away to 70 or 80 percent at very high speed. That’s why I think technology really makes it great and fun to drive a performance car.

When you see how a 2.5-ton Polestar 3 performs like a superb performance car, you don’t feel the weight. Actually, it’s the opposite. That weight, together with the high torque of the engines, is so low that it actually gives you this almost go-kart type of feeling, and it’s amazing how that actually works. The ability to open the door with electromobility gives you such an amazing opportunity to build even greater performing cars. When we take into our comparison drives what was a hero of the performance ICE car, where if we take that into our test, my God, it’s always amazing. Then you get into this ICE car, you rev it, and there’s an amazing noise, but nothing happens because the acceleration in these cars feels so low compared to all the spectacle of noise happening. That’s where even from that aspect, I’m not worried.

Now, putting the third perspective into it, if we don’t get onto the track of electrification, how the hell do we actually think that we manage decarbonization? That is where I would really address politicians. You can’t be that short-sighted that you lose the goal of decarbonization. Let’s be clear: for transportation, what we are talking about is the car that you and I drive. This is the easiest, simplest, and most pleasant way of actually decarbonizing your own personal life. There are many more difficult areas [in terms of] flying around the world. How do you get decarbonization happening there? These are difficult questions. In terms of personal transport with cars that you and I drive, that decarbonization is very quickly possible. The CO2 burden of a Polestar has decreased so nicely.

The Polestar 4 comes with 20 tons of CO2 burden. That is something that you’re within 15,000, 20,000 kilometers before I would say we’re done with it. Then you driving an ICE train would become worse [in terms of CO2] than that. From then on, you’re actually CO2-free if you feed it with green energy. That is actually a very doable and easy thing. A lot of things in your life are much more difficult to decarbonize. And let’s face it, that’s a big challenge for the whole industry, for nations, to get onto that track.

Two things. One, I have done some very entertainingly irresponsible things in a Polestar 2. I agree with you. They’re very fast. And two, I think a lot of people are going to disagree with you about the value of that engine noise over time, but we’ll leave that aside. You mentioned Tesla and it becoming a lower-priced mass-market car. That’s the thing. I think we’re looking at the same piece of evidence in two different ways.

I’m looking at Tesla rapidly slashing the price of the Model 3 over and over and over again, so much so that they’re destabilizing other companies. They’re destabilizing Hertz. They’re destabilizing you, right? Prices of electric cars are coming down fast because Tesla is basically maintaining its sales levels by slashing prices. There’s an argument that Tesla will get to the $25,000 EV just by cutting the price of the Model 3 three more times. They’re already at $35,000.

That’s the piece of evidence I look at that says, “Okay, even the company that was far and away the biggest player in the global EV market is having to slash prices to maintain demand. And it has major competition from Geely, from BYD, that is bringing the prices in the market down.” To you, is that evidence that it’s competition that’s lowering prices? Is that evidence that consumers are no longer willing to pay the premium they were in the pandemic for cars? How are you seeing that play out for Polestar and in the market as a whole?

It’s a different ambition if you want to sell millions of cars. When you actually put out the goal of selling 20 million cars in a year, then you have to be very aggressive in your pricing and you have to be very aggressive in gaining market share there. But that’s a completely different target, a different game.

Do you see Tesla’s struggles as an opportunity for Polestar to take share? Because there is a segment of the Tesla buyer that is right in the strike zone for Polestar.

Well, of course where Tesla started was a completely different end. I mean, they had cars for $100,000 out there.

This is what I’m saying, and the Model S has not been refreshed in a long time.

They left that behind. That is clear. That is where I indeed see a big opportunity for Polestar to address that clientele. Again, they moved into the mass market and left that clientele from the beginning — high-priced Tesla’s, the Model X, Model S — and I definitely think that is a very interesting alternative that Polestar is offering to those customers.

Tesla in particular, design-wise, the interior of the car is very minimalistic. The Model 3 refresh, I think people like it. It’s a very mild refresh. The reviews I’ve read of it so far say we really dislike this new control scheme. They’re pushing everything onto the screen. The interiors are very minimal. That seems to be where they’re saving some cost. You’ve talked a lot about the user interface of the car — like being in the car, experiencing the car. Is that the differentiation here: that you can build a better, more tactile experience in the car?

It’s an acknowledgment that it’s not just a computer on wheels. We actually embrace and cherish some of the great traditions of cars. You mentioned now the noise may be a bit controversial, but other things we actually agree a lot on. A functioning steering wheel is a nice thing to have. But generally, that combination we like. It is a computer, but it is not just a computer on wheels. It is a very emotional, physically moving thing. We saw that when we take the cars onto the ICE track where you very easily, even at low speeds, see how cars behave, how you tune the car, and how you make that incredible power in the car controllable and available to the driver in doses. That’s the element of how this great technology is actually brought into that perfectly tuned masterpiece.

That’s this art of creating a really great car. It’s in a way a very traditional process in order to make that technology really well functioning with great interaction, with great materials, with great love and attention to detail. That’s where we are quite old-fashioned in that respect, cherishing that element of it. Being a European brand, it comes somewhat naturally with the genes that we do it like that. But I see as well that we will always be in that discourse with ourselves.

What is the stuff where we have to push the borders, where we have to be open to modern technology and not be blocked in tradition? And where is the tradition actually very helpful in building a great product? That’s where I would still see us very much on the innovation side. The task is to make people understand that what we did with the virtual mirror is actually something that really embraces modern technology to solve a problem and gives a really great answer — that it’s not just a tech gag but really provides progress.

Somehow we have to convince both sides: trying to be established in the world of driving innovation but at the same time embracing that there is really great stuff in the art of building cars from history,. We have to be very good on both ends and just as much convince the traditional journalist who likes driving our cars but thinks, “Oh my god, this fancy idea of a virtual mirror” that this is great technology. And at the same time, we have to make sure that people understand that we are not just a Scandinavian European brand that is slowly adapting electric technology. We have by now done a number of, for example, over-the-air updates, which became super natural for us.

That is where we are far, far ahead of almost all of the OEMs here in Europe. We actually have that technology very much incorporated, just like Tesla customers are used to over-the-air updates. That’s definitely where Polestar is very much at the forefront of bringing this technology to customers.

If you’re listening to this, Thomas is sitting in front of a Polestar 3, which is in production now. It’s coming out in the summer. If you look at the interior, it is very minimal, and all of the controls have been moved to the screen. You are saying that the software, the screen, the advanced technology, are all stuff you take from the group, and you’re doing a bunch of other engineering.

What’s the balance there? Because that, to me, seems like when you have a brand, and your focus is so much on the brand and the experiences of the brand and making the brand desirable, people get into cars and, over however many years, they’re just going to open Google Maps in their center screen, tell the car where to go, and then play on their phones, and the experience of being in the car is going to diminish over time to almost a commodity.

I look at that screen. I look at the minimal interior here, and I see a big tablet in the middle of a Polestar 3. I say, “That thing is going to eat the rest of the car experience. It’s going to turn all of these cars into just a thing you buy that drives you around.” Is that a worry that you have?

No, because I see this not happening in comparable industries. The Google Maps screen that you see in a car, if what you said were right, then any iPhone user would not cherish the iPhone anymore because, guess what, Google Maps is Google Maps. That’s not the problem. Composing a car, it’s hundreds of elements that make the brand experience in a car, and you do not have to invent everything yourself to offer an amazing product to the customer. It includes bringing in elements that people love and cherish. A lot of people love and cherish the navigation that is provided by the Google Maps system and to have it that nicely and easily integrated. And communicating with the information that the car can deliver makes it more able to predict the right stuff. That’s really where we have to get over that hump.

What makes a brand a brand, and where do you actually create a meal, a dish, that is great for the customer? I always try to say it that way. A great chef in the kitchen doesn’t invent special vegetables. They use the carrot, the onion. It is what everybody else is using as well, but you create a dish that is unique and amazing. That’s how that element of Google Maps comes into our cars.

Last June, you announced a joint venture with a Chinese company called Xingji Meizu. They have a platform called Flyme. That’s the software you’re going to use in Polestar cars in China. Is that because you can’t use Google services in China that you have to go to another provider?

No, that’s not the reason we did it. Not being able to use Google Maps has been the case in China for a long time. We did provide software so far in our cars that had that one navigation system. That’s what we always did before. But we always composed them nevertheless with Chinese elements and a Chinese software offering that, at the end of the day, is very much driven by and decided with a very European mindset. I think that is failing.

It is not working. The speed that we were able to do that within our own organization in China can’t compete with the speed that you need. So very similar to the entertainment system, it’s now something that we do together with the GAS system. It goes that step further that actually the whole phone experience is linked to the software of the car and that unit of phone and car having exactly the same operating system and really making that a unique experience.

That’s the idea behind going together with a mobile phone device company, Xingji Meizu, them bringing their phone and that software into the car, and us delivering the car experience and melting that together. We believe that for the Chinese customer, that experience will be that much more according to their needs and what they expect.

When we did that and had the cooperation going — the Polestar 4 will be the first car that will have the Polestar OS — and two days before the Beijing Motor Show, we will actually present that to a higher degree to the public. I noticed that, the discussion we had. Of course we monitored, “Hey, how are they doing now that this is Polestar OS, which is based on this Flyme base?” We were like, “Oh, do you really want to do it like that?” Naturally, we would have done a different hierarchy and how the interaction is laid out. “Oh, shouldn’t we reduce it and make it a bit more simple and clearer and less visually complex?”

It was interesting to see how our Chinese partner said, “No, no.” I thought, “Yeah, that’s exactly where we would’ve taken a different turn and would have probably done it in our very European way.” I think there is a language barrier. I mean, there are so many different characters. It’s very difficult to do all this interface stuff.

You’re describing to me the central tension of the auto industry outside of the EV transition. Who’s going to own the user interface and, ultimately, who’s going to monetize that user interface? You mentioned app stores. I know that GM and other companies really want to develop app stores and have recurring revenue and take 30 percent the way that Google and Apple do. Volvo CEO Jim Rowan was on the show recently. He was talking about how that’s a bad idea, and he wants to have recurring revenue in insurance programs and other ideas.

There are all these ideas about how to basically get to phone levels of revenue inside the car. Instead of a single purchase, you have an ongoing series of purchases in the car, especially as cars start to drive themselves. Who is going to own that screen is a tension that I think is there.

You can see it with different car makers in different ways. You can see it in the industry. But it hasn’t boiled over. There’s GM, which said, “We’re not going to do CarPlay anymore. We’re all in on Google and we’re going to have our own app store.” That will play out however it plays out. There’s you, you’ve said you’re all in on CarPlay. You’ve talked on this show about how you don’t think that is the central point of differentiation for a consumer, whether it’s Google Maps or not. I’ve heard it from other automakers.

But if you hand over the user experience to another company and say, “The Chinese market demands a different hierarchy of menus,” because that’s what they want. “It’s a totally different operating system with different applications on the screen. It’s a different approach to how we even organize a computer. And in this market, it’s totally different. And in yet another market, Apple’s just going to take over and it’s CarPlay in every car.” At some point, don’t you lose something? It feels like that’s the tension the industry can’t quite articulate but certainly is feeling.

It goes back to that question, who owns the owner? Nobody owns them. They’re having their free decision.

Would you take Apple’s CarPlay that takes over every screen in the car and just let Apple’s operating system run everything in the car? They’ve announced that they have two partners, but it doesn’t seem to be shipping.

Well, you say everything, and there’s the question: what is everything? People thought as well that the GAS system would be the software in the car, as much as it’s not.

By the way, just to clarify, GAS is Google Automotive Services.

The majority of the software of the car is hidden in the background. It is our software that is doing all the drivetrain, the safety, everything. That is where we really talk about this, but it’s an important part. I will not take that away. It’s very important because it’s for the customer.

But it’s not the part of the car that has shopping buttons in it. It’s not the part of the car where people can sign up for subscription services. That’s the monetization that everyone’s headed toward.

But do you think that we will make big bucks with Spotify being in our app store that will now shift our revenue opportunity? That [because] the customer can listen to their Spotify app in our car and their subscription that they have with Spotify, that that makes our car a purchase in the purchase basket? We should not kid ourselves about how much we can develop apps and earn money on them. This is the kind of industry that is not good at developing entertainment apps like Spotify and streaming stuff. Maybe at some point, but I don’t think that’s why Google and Apple are getting into that business. There are completely different opportunities. A big great shift will be the experience of unsupervised piloting in a car: that moment you actually offer something to the customer that is beyond what they experienced so far. I definitely think that that will open revenue streams for the car industry.

The other thing is how much you can keep your car alive and modern. Today, you purchase a car and we clearly no longer have the expectation that the software will always be the same. There will be opportunities to actually upgrade the car, and not totally for free, but there are certain functions and features that you can develop over time that you actually then have a new revenue stream. For example, the unsupervised highway piloting. These are things where I think the value added is where the car companies can actually develop into something more than just selling a car once but also having opportunities for an enhanced experience that you can charge for.

The stuff we have in the app store in the Google system, what comes through what Flyme brings you as an app store experience — I would say these tick the boxes you have to have for customers so that they can access the music channels and entertainment channels that they’re used to when they’re charging so that they don’t take out their phone but actually look at it on the big screen that you have there. For me, it’s naive to think that you could charge extra for customers watching the stuff that they can watch on their phone anyway, just for them to be accessing that in the car.

So let me ask you. Apple has CarPlay where it takes over all the screens, not all the software. Would you do it?

Yeah, of course.

Have they talked to you about it?

Because I know that they’re not taking over. It is a catered experience. Then you have a certain interface that is a bit different from Apple. I believe that we have to be proud enough and powerful enough in thinking that we actually have a very competitive and great original experience that we make together with the GAS system. I’m not afraid of that competition, and it would be strange to prohibit our customers if they have that preference.

I had that experience on a smaller scale. I was in a Polestar 2 in the UK and the driver was running an alternative navigation system: Waze. It’s very popular, and I asked, “Why do you use Waze?” There are certain preferences; they’re used to it. They like that that car app does this and that. Fine, if they want to have Waze, then run Waze in our cars. Of course we should cater to them. Now we actually do it natively. They don’t have to do it through their phone anymore. Now that app is included, and you can push the button. Instead of Google Maps, you run it on Waze. I really think we are here to provide to the customer the ability to use the car the way they want to use it and not to be dogmatic about, “Oh no, we don’t offer that.”

Alright, I only have a few minutes left with you. You’re a designer, and I like asking you about car design. In 2021, you were on the show. It was the height of what I would call the “angry robot era” in car design, particularly from the Japanese brands. I asked you about BMW’s nostrils. I think that era has changed. We are in an interesting sort of retrofuture moment. That’s Hyundai and Kia, for sure, but also the Rivian R3 designs. The R3X, in particular, is very retrofuturistic, very organic. What do you think is happening here? Is this consumer demand? Is this just a design trend? How are you thinking about it?

It’s the way it goes. It’s history. It’s history taking place. Car design is developing, it’s according to society streams. It’s always a reflection of what’s happening in culture and in society. I see that as well, and I actually applaud it. I’m happy that we are out of this super aggressive [period], and then again, it’s of course a reflection of the period the whole world is in. The danger that I see is that instead of developing new expressions and new formative elements, that you are reflecting too much on what has happened in the past. That’s the tricky bit of making now that translation into, “Come on, yes, we cherish certain historical values and great car design, but how do you drive it into the future? How do you make it a modern trend and not just a retro trend?”

But it’s good, and great creativity is out there. It’s fun now again to actually go to whatever car show is going on and see what’s happening there. It’s obvious that there is a certain, I call it, “unsecurity” on testing new ground and trying things. You see how, for example, BMW is putting out a study of what their future direction can look like, but it’s great that companies feel the need and the necessity to define and open that new epoch and actually enter it. Partly, it makes our story easier because certain elements that we have been promoting some years ago obviously find recognition, and that makes it, for the customer choosing our cars, kind of a confirmation that the style we are promoting actually is what is leading the future.

Do you see that turn toward retrofuturism or safer designs? It felt like EVs inspired a lot of companies to get as radical as possible because the packaging of the car was different. You didn’t have a transmission tunnel. You could do a frunk. You could do anything you wanted. The EV is just packaged inherently differently, and so there was a push toward radicalism. Some companies pushed very safely. The F-150 Lightning is an F-150. Do you see that coming into a coherent place where it’s like, “Okay, people just want the EV drivetrain and they want a cool car”? Or are we still in that, “Actually we can package the car entirely differently”?

I’d say it’s a bit more sophisticated now. It’s not just, “Ah, here’s a bright white field. Let’s just run.” It has to make sense. I mean putting meaning into it. That’s certainly one element. The other element is the recognition that it’s not just enough to look futuristic; you still have to work on giving your brand profile. So the face of the car just looking futuristic is not good enough. There are 20, 50 cars out there now that look futuristic on first glance. Now, you definitely have to be that much more sophisticated in crafting it and finding your expression of it. So that’s where we definitely reached beyond that first wave. We are now in a time when, yes, clearly, electric car design is driving the future of car design.

I mean, guess what? We are talking about car design. Would you discuss the future trend of hybrid cars? No, of course not. There’s this one trend of car design, and it is very much influenced by electric cars, and that’s where we are now in that more sophisticated stage., How does that type of electric car design look now become that sophisticated brand expression? Different categories of cars actually find their craftsmanship, their category, their catalog of expression. I’m definitely embracing that we are beyond that first happiness about the car just looking futuristic.

There’s retrofuture, there are organic shapes, there’s “everybody calm down.” Then there’s the Cybertruck, which is an angry triangle. Does that represent anything to you, or is that just a design direction where you’re interested in seeing what happens?

It’s a very iconic design and shape. Yeah, you can do that once, but it doesn’t define a car line. That’s where I don’t see how that would start a new trend. It’s a very exotic singular moment in car history, and for that reason, great. I embrace it. It’s very brave and a technical challenge to do it, but aesthetically it has its limitations. For that reason, it’s always amazing to see that car history is full of these individual moments that have happened — something that was amazing, outstanding, but in a way, it did not lead to much. Ask me in two years, but at the moment, I can’t see that [the Cybertruck] would lead to anything beyond that one single product.

I think “Aesthetically it has its limitations” is my new favorite response to things. I’m just going to hold onto that forever. Thomas, this has been wonderful. Tell the people what’s next for Polestar. What should they be looking for?

Well, [Polestar] 3 and 4 on the road. That will hopefully be an amazing experience to see these cars not just on the front of a magazine but actually see them passing by. That’s still one of the things I experienced that, again and again, whatever we try to visualize, it’s only when you have the chance to see it on the road that you actually grasp the dimension of it and what it really does. So that’s of course very exciting. What should people expect from us? Definitely developing the element of performance in our brands.

We started with the beast edition of the BST edition of the Polestar 2. I call it now, cheekily, that fun of having electric cars — the culture of a fun, desirable car. That’s the element we want to embrace when we have the Polestar 3 and 4 out. The 5 will come, and that’s definitely in prototype actually in Coventry last week. It’s so amazing to see that car come together. So 2025, it’s coming on the road. I think that completion of having done the range of 2, 3, 4, and 5. Then you have a brand — Polestar — how we always envisioned it in the first place, and I’m really looking forward to people being able to see it on the road.

Polestar famously launched with the Polestar 1, which was a hybrid. A very high-performance hybrid — a GT, it was a cool car. Hybrids are having a little bit of a resurgence here in the US. You can see the sales growth. You can see politicians and car makers are saying hybrids are the way because they solve the range of anxiety problem. Would you ever do a hybrid again?

Never say never. Having said that, technology is moving, and we definitely would have to embrace innovation to a much bigger extent, and we can’t just do the hybrid as it was. I believe as well, if we want to do something like a Polestar 1 with that performance, nothing beats electric power. It would be very difficult to do something that can compete with a pure electric performance car. Show me the tech that can beat that, and then we are talking.

Great. Well, Thomas, thank you so much for being on Decoder. I really appreciate it.

Pleasure, and thanks a lot for the time you gave me here.