Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s claimed victory for his alliance in India’s general election, despite a lackluster performance from his own party.

Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party party faced a stronger challenge from the opposition than expected after it pushed back against the leader’s mixed economic record and polarising politics.

“Today’s victory is the victory of the world’s largest democracy,” Modi said, speaking at his party headquarters.

For the first time since BJP swept to power in 2014, it might not secure a majority on its own, according to the ongoing vote count on Tuesday — but the prime minister was still expected to be elected to a third five-year term in the world’s largest democratic exercise.

If Modi has to rely on coalition support to govern, it would be a stunning blow for the 73-year-old, who had hoped for a landslide victory.

Despite the setback, many of the Hindu nationalist policies he’s instituted over the last 10 year remain locked in place.

Modi pledged to make good on his election promise to turn India’s economy, the world’s third biggest, from its current fifth place, and not shirk with pushing forward with his agenda.

He said he would advance India’s defence production, boost jobs for youth, raise exports and help farmers, among other things.

“This country will see a new chapter of big decisions. This is Modi’s guarantee,” he said, speaking in the third person.

In the face of surprising numbers, both sides claimed they had won some sort of victory.

“People have placed their faith in the NDA, for a third consecutive time,” Modi wrote on social media platform X, referring to the National Democratic Alliance that his party heads.

“This is a historical feat in India’s history.”

Meanwhile, the main opposition Congress party said the election had been a “moral and political loss” for Modi.

“This is public’s victory and a win for democracy,” Congress party President Mallikarjun Kharge told reporters.

The counting of more than 640 million votes cast over six weeks was set to take all day, and early figures could change.

In his 10 years in power, Modi has transformed India’s political landscape, bringing Hindu nationalism, once a fringe ideology in India, into the mainstream while leaving the country deeply divided.

His supporters see him as a self-made, strong leader who has improved India’s standing in the world. His critics and opponents say his Hindu-first politics have bred intolerance and while the economy, the world’s fifth-largest and one of the fastest-growing, has become more unequal.

Some eight hours into counting, early leads reported by India’s Election Commission showed Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party was ahead in 231 constituencies and had won 13, including one uncontested, of 543 parliamentary seats. The main opposition Congress party led in 93 constituencies and had won four.

A total of 272 seats are needed for a majority. In 2019, the BJP won 303 seats, while it secured 282 in 2014 when Modi first came to power.

Modi’s party is part of the National Democratic Alliance, whose members led in 277 constituencies and won 15, according to the early count. The Congress party is part of the INDIA alliance, which led in 220 constituencies and had won five.

The Election Commission does not release data on the percentage of votes tallied.

Markets down sharply on early results

Exit polling from the weekend had projected the NDA to win more than 350 seats. Indian markets, which had hit an all-time high on Monday, closed sharply down Tuesday, with benchmark stock indices — the NIFTY 50 and the BSE Sensex — both down by more than 5 per cent.

In the financial capital of Mumbai, Mangesh Mahadeshwar was one of many surprised by how the election was playing out.

“Yesterday we thought that the BJP would get more than 400 seats,” said 52-year-old who was keeping an eye on the results at the restaurant where he works.

“Today it seems like that won’t happen – people haven’t supported the BJP so much this time.”

If Modi wins, it would only be the second time an Indian leader has retained power for a third term, after Jawaharlal Nehru, the country’s first prime minister.

But if his BJP is forced to form a coalition, the party would likely “be heavily dependent on the goodwill of its allies, which makes them critical players who we can expect will extract their pound of flesh, both in terms of policymaking as well as government formation”, said Milan Vaishnav, director of the South Asia Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

“This would be truly, you know, uncharted territory, both for Indians as well as for the prime minister,” he said.

Before Modi came to power, India had coalition governments for 30 years. His BJP has always had a majority on its own while still governing in a coalition.

Temperatures top 45 degrees amid voting

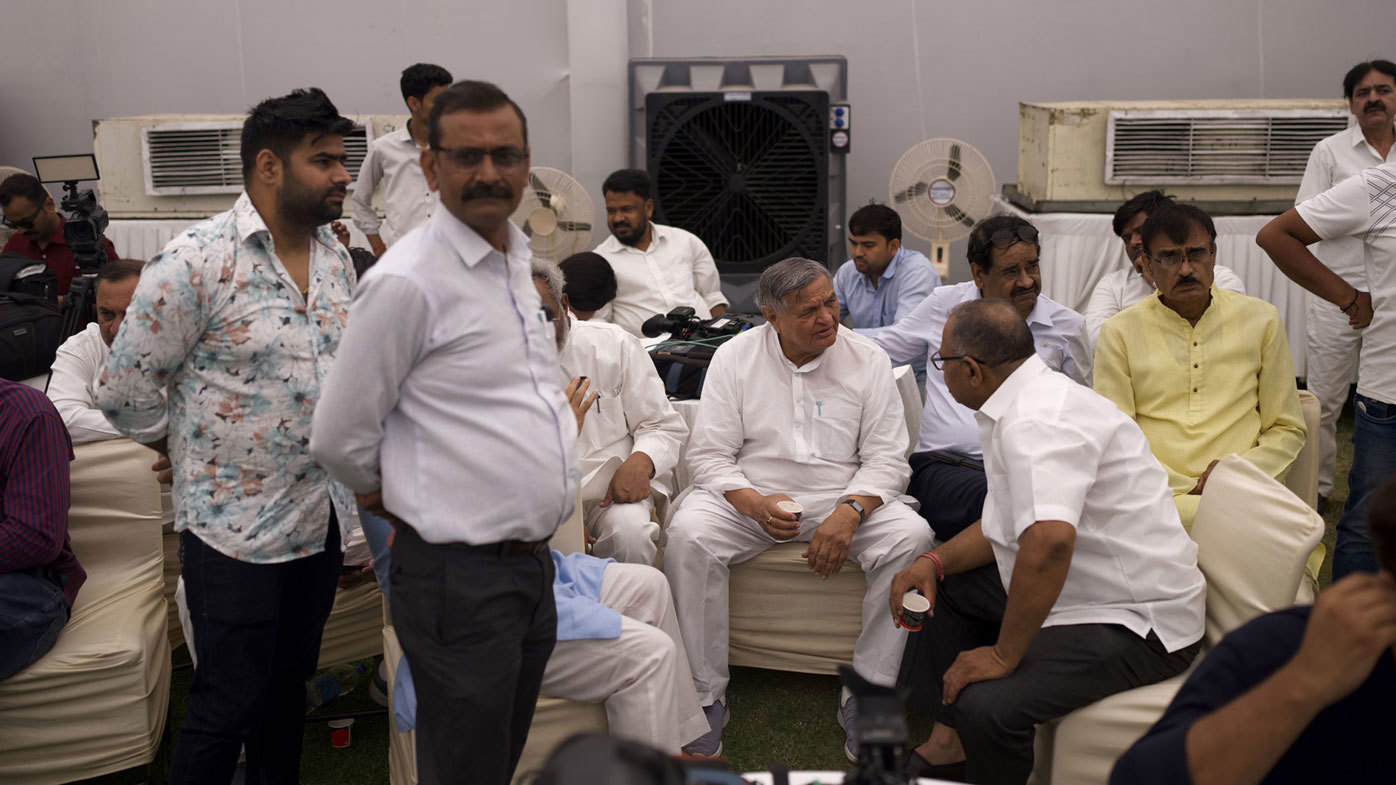

Extreme heat struck India as voters went to the polls, with temperatures higher than 45 degrees in some parts of the country. Temperatures were somewhat lower on Tuesday for the counting, but election officials and political parties still hauled in large quantities of water and installed outdoor air coolers for people waiting for results.

BJP workers outside the party’s office in New Delhi performed a Hindu ritual shortly after the counting began. Meanwhile, supporters at the Congress party headquarters appeared upbeat and chanted slogans praising Rahul Gandhi, the face of the party’s campaign.

Over 10 years in power, Modi’s popularity has outstripped that of his party’s, and turned a parliamentary election into one that increasingly resembled a presidential-style campaign. The result is that the BJP relies more and more on Modi’s enduring brand to stay in power, with local politicians receding into the background even in state elections.

“Modi was not just the prime campaigner, but the sole campaigner of this election,” said Yamini Aiyar, a public policy scholar.

Critics say democracy is faltering

The country’s democracy, Modi’s critics say, is faltering under his government, which has increasingly wielded strong-arm tactics to subdue political opponents, squeeze independent media and quash dissent. The government has rejected such accusations and say democracy is flourishing.

And economic discontent has simmered under Modi. While stock markets reach record-highs and millionaires multiply, youth unemployment has soared, with only a small portion of Indians benefitting from the boom.

As polls opened in mid-April, a confident BJP initially focused its campaign on “Modi’s guarantees”, highlighting the economic and welfare achievements that his party says have reduced poverty.

With him at the helm, “India will become a developed nation by 2047”, Modi repeated in rally after rally.

But the campaign turned increasingly shrill, as Modi ramped up polarising rhetoric that targeted Muslims, who make up 14 per cent of the population, a tactic seen to energise his core Hindu majority voters.

The opposition INDIA alliance has attacked Modi over his Hindu nationalist politics, and campaigned on issues of joblessness, inflation and inequality.

But the broad alliance of over a dozen political parties has been beset by ideological differences and defections, raising questions over their effectiveness.

Meanwhile, the alliance has also claimed they’ve been unfairly targeted, pointing to a spree of raids, arrests and corruption investigations against their leaders by federal agencies they say are politically motivated. The government has denied this.

Women are a key voting bloc in India’s 2024 election

Indian women are a key voting bloc with more of them voting in recent elections than ever before. Most poll experts expect women voters to play a decisive role in determining the 2024 election results.

Political parties have been wooing them with monthly cash handouts, subsidised cooking gas cylinders and low-interest loans. Many such programs have particularly helped Modi’s Bharatiya Janata party widen its support among them, especially in rural areas.

The opposition alliance also tried to gain women’s votes by unveiling programs that promised financial aid of US$1200 ($1800) per year to poor women, and promised to reserve 50 per cent of government jobs for women if voted into power.

Women make up nearly 49 per cent of India’s total electorate. Turnout has grown in each recent major election – of women who were eligible to vote, 53 per cent voted in 2004; 56 per cent in 2009; 65.5 per cent in 2014; and 67 per cent in 2019. Data for 2024 was not yet available but was estimated to resemble 2019’s female voter turnout.