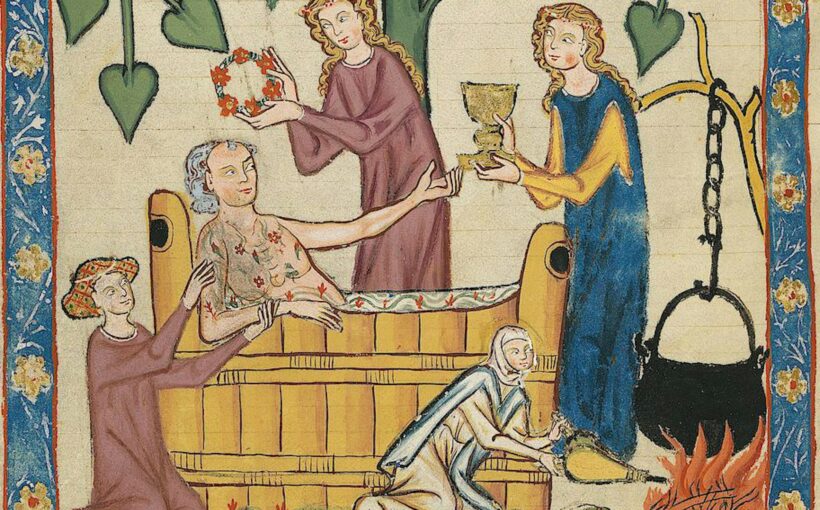

On June 8 1023, 1,001 years ago, King Cnut took a bath. In itself this was not particularly remarkable. Contrary to the image of a ubiquitously grubby middle ages that dominates film and television, there is evidence to suggest that among the upper classes, at least, bathing was a regular pleasure.

What is unusual is that Cnut’s bath seems to be the first in English history that a (fairly) reliable written source, Osbern of Canterbury, chooses to pin to a particular time and place. But why? What made this particular bath 1,000 years ago deserving of this honour? The answer lies in the complex world of 11th century national power politics.

First we need to go back to 1012 and the grisly fate of Ælfheah, archbishop of Canterbury. Captured the previous autumn by a band of Vikings, Ælfheah was considered a valuable prize. By the spring, the leader of the band, Thorkell the Tall, was trying to negotiate a ransom for him from the English, while holding him captive at an encampment in Greenwich.

Disappointingly for the Vikings, Ælfheah refused to be ransomed. This courageous move placed the archbishop in a distinctly perilous position. He was a rapidly depreciating asset in the hands of a bunch of rowdy and bloodthirsty men, who were happy to take their amusements where they found them.

At a feast on April 19 1012, his captors threw “bones and the heads of cattle” at him until eventually one of them, a Christian convert, took pity and despatched him with an axe-blow to the head. St Alfege’s church in Greenwich supposedly stands on the site of the martyrdom.

Ælfheah’s body was buried in St Paul’s Cathedral, where it lay for the next 11 years. In the meantime, the Danes completed their conquest of England.

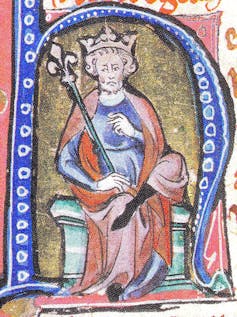

The Dane Cnut, crowned king in 1016, set about the business of reconciling himself to his new English subjects. And as a dead man, Ælfheah gained more political power than he had had when alive. The corpse of the archbishop, casually slaughtered in a peculiarly gruesome way during a drunken binge, was a continuing reproach. It was a reminder of a version of the Danes that did not square with Cnut’s aspirations to godly English kingship – particularly while it remained uncomfortably close to where the deed itself had occurred.

Cnut decided to have Ælfheah reburied in Canterbury with full honours. The move would at once acknowledge the enormity of the crime and hail the sanctity of the archbishop (harnessing it to his own regime). He hoped it would neutralise Ælfheah’s power as a nexus of friction between his English and Danish subjects.

Putting his plan into effect, Cnut summoned Ælfheah’s successor as archbishop of Canterbury, a man named Æthelnoth, to London. He was to preside over proceedings so that they were seen to be carried out with the blessing of the church.

At this point we can return to Cnut’s bath. Barely had he entered it, Osbern tells us, when a messenger arrived to tell him of Æthelnoth’s arrival.

Cnut – achieving the dubious honour of being the first person recorded in English history to have been disturbed by something frustratingly urgent just as he had stepped into a bath – immediately arose, dried himself and embarked for St Paul’s to take control.

The body of a martyr was a valuable spiritual, and perhaps also commercial, commodity. Cnut knew that any attempt to take it away from London would almost certainly be resisted.

Cnut ordered his men to create a distraction while the tomb was opened by a vigorous pair of monks named Godric and Ælfweard the Tall (who proved surprisingly adept at surreptitiously demolishing cathedral walls). The corpse of Ælfheah was retrieved and spirited away to a ship on the Thames (with Cnut himself at the helm) under the very noses of the citizenry of London.

Ælfheah was then taken on to Canterbury to be reburied, becoming the focus of a minor, but politically useful cult. Canonised in 1078, there are a scatter of churches dedicated to him (normally as St Alphege) in England. The document which tells us the story (Translatio Sancti Aelfegi, Translation of Saint Aelphegus), was produced at Canterbury by Osbern in the 1080s. He wrote it alongside a Life of Ælfheah as part of a campaign to ensure his recognition as a legitimate saint in the aftermath of the Norman conquest.

The Normans regarded most pre-conquest English saints with scepticism. So Osbern, wrote these tracts to bolster Ælfheah’s status and guarantee that the saint would continue to attract gifts, pilgrimages and benefactions to the diocese with which he was strongly associated. To the city of Canterbury, Ælfheah was a valuable piece of intellectual property and it was vital to protect it.

There is a great deal to unpack in this story, but the focus on Cnut’s interrupted bath in Osbern’s account is an especially fascinating nugget. Writing some 60 or so years after the events in question and using sources that are entirely unknown, why did Osbern feel that this element of the story deserved attention?

It certainly brings the story alive and gives it – at least to modern eyes – a vividness, immediacy and interest it might otherwise lack. But for the medieval audience, the story of Cnut’s immersion at this critical moment would have overtones of a spiritual rebirth akin to Christian baptism.

Osbern’s implication is that as a reward for removing Ælfheah’s remains to Canterbury and doing them proper honour, the saint will cleanse Cnut of his sins – and of any residual guilt for deaths during his conquest of England. This is represented in physical form by his immersion in water, awakening him through this baptism to a virtuous life in Christ as a godly English monarch.

Through the surprising medium of this first recorded English bath, the divided and conflicted English kingdom of a millennium ago opens up to us.

![]()

Simon Trafford does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.