One of the few success stories of the Conservative government is the fall in inflation, which is now close to the target rate set by the Bank of England. In April 2024, the consumer price index, the most common measure of inflation, increased by 3% over the previous year compared with a 9.6% annual increase in October 2022.

However, this good news for Rishi Sunak and the government has not moved the dial by changing voting intentions in the polls. According to the BBC tracker poll of polls, the Conservatives are currently 21% behind Labour in voting intentions, a gap which has not really changed since Liz Truss departed from Downing Street in October 2022.

This is a puzzle because one the best established findings in political science is that the economy always plays a big role in influencing voters in elections. At the moment, the most important issue in the election campaign is the state of the economy, particularly the cost-of-living crisis. Since this issue is very salient it should help the Conservatives, but it appears to be making no difference.

This anomaly could be explained by other factors looming large in the minds of the voters such as the state of the NHS, the issue of immigration, the performance of the party leaders in the campaign, internal divisions in the parties and so on. In other words, the government’s policy success on inflation is being drowned out by other things going on in the campaign.

Want more election coverage from The Conversation’s academic experts? Over the coming weeks, we’ll bring you informed analysis of developments in the campaign and we’ll fact check the claims being made.

Sign up for our new, weekly election newsletter, delivered every Friday throughout the campaign and beyond.

However, there is a more plausible explanation, namely that voters would have to have short memories to reward the Conservatives for reducing the cost of living. For this to work, voters would have to forget the dark days of rampant inflation just after the pandemic, which coincided with the start of the Ukraine war and instead focus on just the last few months.

However, the evidence shows that voters judge what happened to the economy over a longer period than a couple of months.

A century of economic voting

We can examine the effect of the economy on voting by looking at relationships over a long period of more than a century. This involves modelling how inflation and unemployment have influenced voting for the governing party or coalition in the 27 successive elections since the end of the first world war. This analysis begins in 1922, the first fully peacetime election, and ends in 2019, the most recent general election.

There are different theories about how economic voting works, but the simplest is the so-called “reward-punishment” model. According to this, high levels of inflation and unemployment cause a decline in support for incumbents as voters punish them. And low levels of these variables increase support as voters reward them.

These factors affect voting over successive elections, which implies that voters remember what has happened during the entire inter-election period.

The period since 1922 has included some significant economic shocks, such as the great depression of the 1930s and the financial crash and subsequent recession of 2008, not to mention the second world war. There were also many political events which could have distracted voters from the economic effects of government policies. This provides a test of whether the issue of the economy is crowded out during election campaigns by other issues and intervening events.

It turns out that a very simple regression analysis shows how important the economy is in elections over this period. The model involves forecasting the vote share in elections for the incumbent party or coalition government using contemporary data on inflation and unemployment.

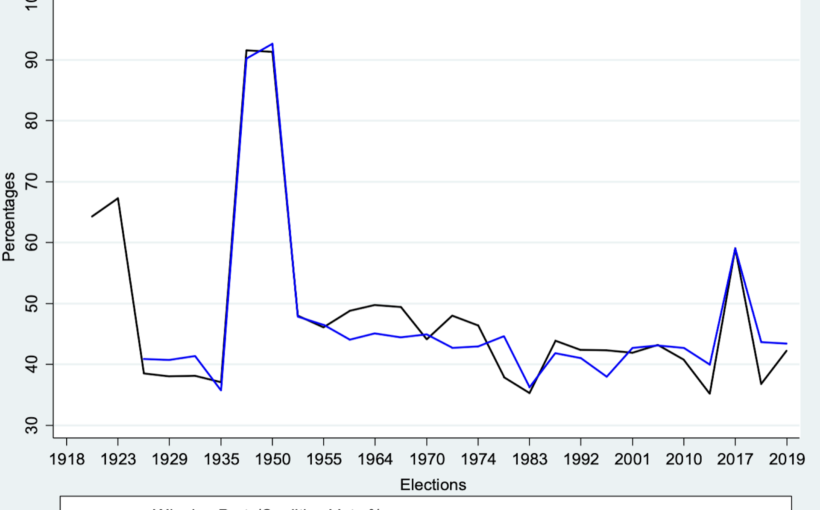

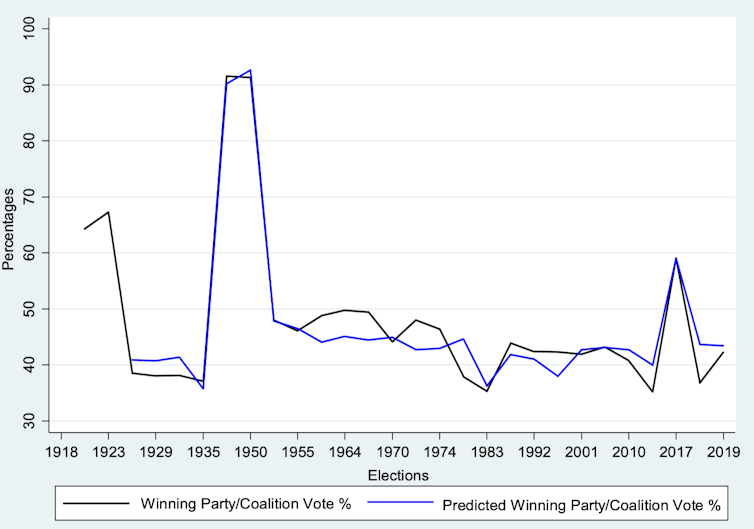

The chart below shows the actual performance of the incumbent government and the predicted performance from the model. In the event, the model is a pretty good predictor of what happened.

Actual and predicted voting for incumbents based on inflation and unemployment as predictor of voting, 1922 to 2019:

It is important to differentiate periods of single party government from coalition governments. This is because attributions of responsibility for the economy by the voters are easy if one party is in power, but more difficult if it is two or more parties. Thus, periods of coalition government are taken into account in the analysis.

An example of this is the big upswing in voting for incumbents in the 1935 election, which passed judgement on the national government of 1931 created in response to the start of the great depression in 1929. Labour was in power earlier in 1929 and the prime minister, Ramsey Macdonald, split his party and joined a coalition with the Conservatives in response to the crisis. We combine the Conservative and Labour votes in that year reflecting the fact that both parties were in government at the time.

Looking at the details of the model, both unemployment and inflation had significant negative impacts on support for incumbents with the effect of unemployment being slightly larger than inflation. There was an important difference between the two variables, however.

The levels of unemployment affected support for incumbents, but in the case of inflation it was the change in the cost of living which counted. Voters are often confused about the meaning of inflation, since it represents a change in prices rather than the level of prices. In this case, we are talking about a change in inflation between elections.

The implication is that the voters dislike both unemployment and inflation, and they punish incumbents for both. But they tend to get used to inflation unless it starts growing rapidly. If this happens it wakes them up to the effects on their wages and on prices in the shops.

That said, the adjustment takes longer than a few months, so voters are unlikely to forget the rocketing prices of a couple of years ago even when inflation subsequently comes down. In contrast, they don’t get used to high levels of unemployment if it remains stable for a long period.

The economy is the number one issue in the present campaign and when the voters look at what has happened since the 2019 election, it does not surprise that many are no longer supporting the Conservatives.

![]()

Paul Whiteley has received funding from the British Academy and the ESRC