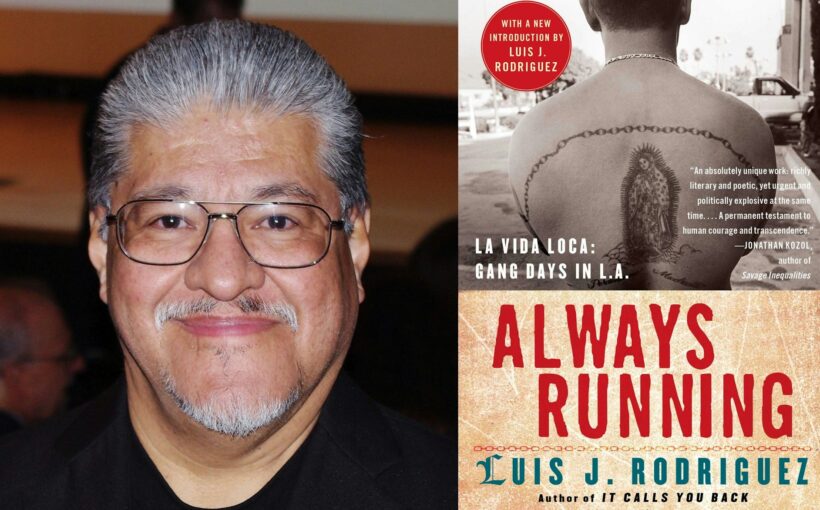

In the same year the poet and activist Luis J. Rodríguez prepares to celebrate his 70th birthday (on July 9), his bestselling memoir Always Running celebrates its 30th anniversary.

In Always Running, Rodríguez reflects on his involvement with Mexican-American gangs in east Los Angeles (LA) during the 1960s and 1970s. Released in 1993, the memoir is memorable for its violent tales of barrio life balanced with an articulate, politicised vision of the structural conditions shaping these underclass realities.

As the authors of a groundbreaking new anthology about his life and legacy, we believe Always Running is as relevant today as it was in the early 1990s, for its discussion of social and structural problems.

Always Running remains a strong feature on US high school reading lists, often flagged as potential material for “reluctant readers”. According to some reports, it also is the most stolen book in the LA public library system. Many of the book’s themes, including structural racism, inequalities and poverty, as well as selectively underfunded and therefore de facto segregated education, are as topical now as 30 years ago.

Rodríguez’s graphic narrative addressed the infamous LA riots of 1992 in both the preface and epilogue, using the uprising as well as the incarceration of his son, Ramiro, to frame tales of gang conflict with a conversion narrative. All the while, the memoir argues that creativity has the power to heal and help plot a way out of the morass.

In 2023, we were the first academics to work in the Rodríguez archives, his personal papers that had been acquired by the Special Collections Library at the University of California, Santa Barbara. In the same year, a 200-foot-high mural was unveiled at the historic Watts train station in LA bearing Rodríguez’s poem Watts Bleeds.

The poem was published shortly before Always Running and its public unveiling was to mark the 30th anniversary of the memoir. Characteristic of Rodríguez’s memoir as well as his poetry more widely, the verse on the side of the train station captures the raw underside of LA that he experienced as a child:

Watts bleeds

dripping from carcasses of dreams:

Where despair

is old people

sitting on torn patio sofas

with empty eyes

and children running down alleys

with big sticks.

In poignant language and visceral images that haunt long after the lines are read, the remainder of the poem speaks to the histories and dreams of black and brown residents of this inner-city neighbourhood in south LA. And it recalls all those who have been overlooked (“vacant lots/and burned-out buildings – temples desolated by a people’s rage”).

Yet the poem – and the memoir – could be written for LA today. Since COVID the city has struggled with ever-growing homeless encampments and just over 15% of the city’s population lives below the poverty level. An article in The Guardian in January 2024 revealed that police officers in California still stopped and searched black and Latinx drivers at significantly higher rates than white people, which adds to the already stark racial disparities in the US prison system.

Writing about Always Running’s anniversary in the LA Times, journalist Gustavo Arellano contended that the narrative is a “manual for LA’s salvation”. He deems the memoir a literary companion to Marxist scholar and public intellectual Mike Davis’s exposé of the carceral reality, City of Quartz, published three years earlier.

But we believe that Always Running’s ongoing significance is a testament to the complex life of a man who has unwaveringly used his access to institutions of power to serve the underclass community that weaned him.

The book’s continued popularity speaks to the universality of his work to illuminate and intervene into the plight of the underclasses, workers, abused and wounded survivors of violence. The narrative speaks to the material and spiritual dimensions of reclaiming humanity at the personal, interpersonal and global levels.

Rodríguez’s son, Ramiro, has long since been released from prison. But Rodríguez’s dedication to proletarian politics and concerns for the working classes, interlinked with his focus on “real-life” issues, has made him – and Always Running – popular with readers across time and space.

These readers use Rodríguez’s writings and other related endeavours as touchstones for interpreting and understanding contemporary US society and culture in relation to the world at large.

![]()

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.