Germany is hosting the Uefa Euro 2024 men’s football tournament right in the middle of what has been called the country’s “super election year”. People are voting at local, state and European levels, amid renewed contests over Germany’s relationship with its Nazi past.

The European elections have seen a noted rise in right-wing populism across the bloc. The long shadow of national socialism, however, means that far-right gains in Germany inevitably attract more attention.

Debates around difficult periods of the national past tend to coalesce around the traces left in the built environment. Overtly Nazi statues and symbols were removed soon after the defeat of the Third Reich. However, many of the regime’s vast, monumental buildings remain in use.

On July 14, 2024, images of the Euro 24 final will be broadcast across the world from the Olympiastadion, Berlin’s Olympic Stadium built in 1936. With the rise of the German far-right and its effective use of TikTok and historical misinformation, historians and campaigners concerned with how the Nazi past is presented need to find new tactics to counter their rhetoric.

Politics of the past

Despite widespread protests, the far-right party, Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), has gained significant ground. Membership is at an alltime high. It garnered 15.9% of the vote in the European Parliament elections, coming in second. And it is likely to win in three federal state elections in September.

Prominent AfD members have courted controversy through invoking the Nazi past. Former co-leader Alexander Gauland has been accused of trivialising the Nazi era by labelling it “birdshit”. Björn Höcke, who leads the Thuringia branch, has twice been fined for using Nazi language. And former top candidate, Maximilian Krah, was ejected from the party’s European Parliament delegation after telling an Italian newspaper that members of the SS were not necessarily criminals.

This has caused alarm that the lessons of history – that the Federal Republic has long prided itself on learning – have not been as effective as once thought.

Propaganda apparatus

The built environment was key to the Nazi propaganda apparatus. Buildings were designed to convey Nazi ideology. And they featured heavily in newspapers and magazines, throughout the 1930s and 1940s, as evidence of the new regime’s power and assertiveness.

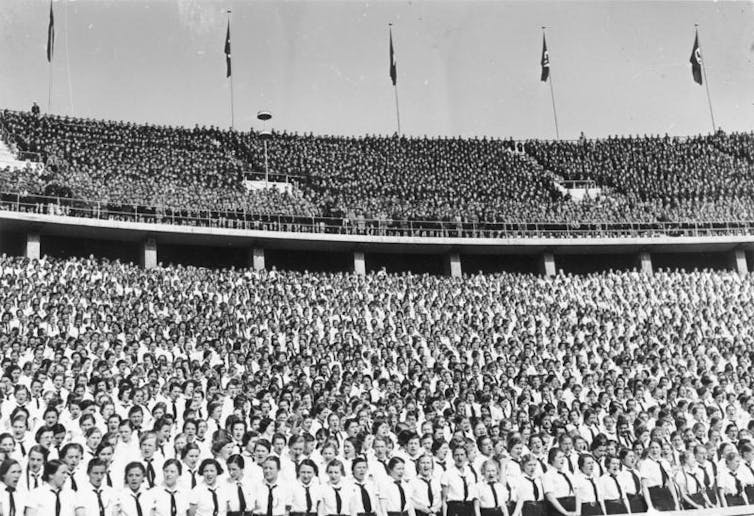

The Olympic Stadium was designed by the German architect, Werner March, for Hitler’s so-called “peace Olympics” of 1936, which the Nazis used to assuage growing international fears of German militarism and mask the escalating persecution of Jews, political opponents and the other groups they labelled “undesirables”.

Hitler took an active interest in the stadium’s design. Its monumentality and stone-cladding express the power and durability of the Third Reich. The stadium’s form, columns and sculpture collection allude to the regime’s supposed connection to antiquity.

Individual sculptures convey Nazi ideas including the supremacy of the healthy, Aryan body and the connection between sport and war. The bell tower that dominates the site stands above the Langemarck Hall, a memorial which originally contained blood-stained earth from the 1914 battlefield. The intention was to incorporate the Olympic site into the Nazi cult of the dead.

Critical engagement

After the second world war, the British Allies established their headquarters in the northern part of the Olympic Complex and handed the rest back to the West Germans. The stadium became home to the Hertha BSC football team in 1963. It was subsequently developed into a popular venue for sport and entertainment events.

For decades, architects, historians and politicians have called for more critical engagement with the history of the Olympic Stadium building. They decried the lack of information about its origins and symbolism.

It was only after Germany bid (unsuccessfully) for the 2000 Olympics and (successfully) for the 2006 World Cup that these calls began to attract wider attention and, crucially, money. Debates raged over whether the sculpture collection should be removed, covered up or left alone.

Ultimately the Berlin Senate agreed that the most effective way of dealing with the site’s history was to preserve it and provide visitors with information that enabled them to think independently and critically about it. To this end, a history trail of 45 information boards was developed by a panel of experts.

The resurgence of far-right activity in recent years has exacerbated fears that this is not enough and has seen debates over removing the statues be reignited. Volkwin Marg, one of the architects who renovated the Olympic Stadium in 2004, has described the information boards as “little noticed”, “little advertised” and “powerless”.

The far-right has demonstrated a striking ability to communicate its messages through TikTok. A recent study by the Anne Frank Education Centre found that four of the platform’s top five political influencers in Germany were from the AfD. It showed that Tiktok is being used to spread right-wing ideology and generate considerable support among young people.

The report’s authors warn that those wishing to counter far-right ideas need to overcome their “technophobia” and harness similar communication techniques.

This is a huge challenge to those using more traditional methods to educate people about the past. The creators of the Olympic Stadium’s history trail recommend it be advertised more clearly and augmented with an app. They also support Marg in demanding the construction of an exhibition in the Langemarck Hall and an increase in the number of staff for public education work.

Others call for more innovative approaches. Some would like to see the sculpture collection challenged with a counter-exhibition of images depicting the types of bodies the Nazis sought to eradicate.

The German and Berlin governments have allocated €403,000 for art and culture projects which, as Minister of State for Culture, Claudia Roth puts it, reflect “an image of a bright, diverse, inclusive society, of a democratic Germany”. This includes sports outreach programmes and an exhibition on football under the Nazis co-organised by the World Jewish Congress, Berlin Sports Museum and What Matters, to be held near the stadium, on the Olympic site, throughout Euro 2024.

This is part of a much larger Football and Remembrance project run by What Matters, the German Football Association’s Cultural Foundation and the World Jewish Congress. This will see memorial sites and museums across Germany holding events and exhibitions for both German and international visitors about persecution and sports under Nazism throughout the Euro 2024 competition.

Some Germans will return to the polling booths in September for state elections in Thuringia, Saxony and Brandenburg. Whether or not these measures will impact on the AfD’s predicted successes remains to be seen.

![]()

Clare Copley has received funding from the AHRC, the Institute of Historical Research and the Universities of Bristol, Sheffield and Central Lancashire