Shootings in America often prompt expressions of relief in the UK that a calmer and less violent society is in evidence. But few will have responded to the attempted assassination of Donald Trump with any complacency about the safety of politicians in Britain. The murders of two MPs, Jo Cox and David Amess, are still fresh in the memory.

At the beginning of the new parliamentary term, the House of Commons speaker, Lindsay Hoyle, said that he has “never seen anything as bad” as the current level of threats and intimidation being directed at MPs.

Want more politics coverage from academic experts? Every week, we bring you informed analysis of developments in government and fact check the claims being made.

Sign up for our weekly politics newsletter, delivered every Friday.

The murders of Cox in 2016 and Amess in 2021 mark the appalling extreme of this phenomenon. Compared to murder, of course, online trolling, milkshake hurling, smashing windows or painting threatening messages on politicians’ offices may appear trivial. But it is the seemingly routine nature of such incidents that makes for such a slippery slope between insult to overt physical violence.

We know that exposure to such incidents tends to erode the wider norms against violent behaviour. That, in turn, emboldens perpetrators. And we’ve also seen that polarisation, especially over the EU referendum, has created a climate in which politicians on “the other side” are not only seen as opponents but enemies – and even traitors. Someone applying the logic that “my enemy’s enemy is my friend”, which is an insidious yet pervasive feature of polarised politics, might prove worryingly tolerant of threats or attacks against those politicians.

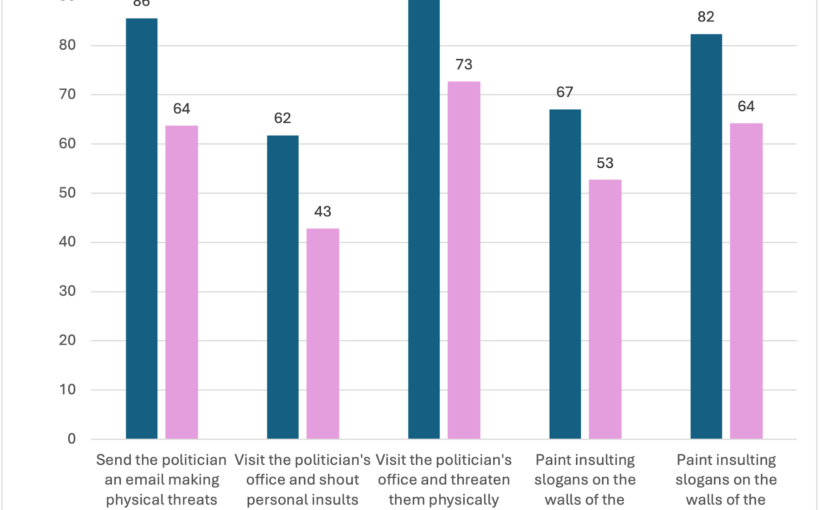

But the British public doesn’t, it seems, subscribe to this view. In fact, when we conducted a survey during the final week of the election campaign – a time when candidates are at their most exposed and when tensions are running highest – we found that the public skewed heavily towards condemnation of those who abuse or threaten politicians. Their opposition was strongest when it came to making physical threats against a politician at their office or surgery. On a seven-point scale from “never acceptable” to “completely acceptable”, fully 90% chose the “never” option. Only 1% were to the “acceptable” side of the midpoint.

The picture is a little less rosy – or at least more nuanced – if we look at vandalism of MPs’ private property. Some people regarded these behaviours as at least somewhat understandable, even if not acceptable. But people tended more towards the “never understandable” end of the scale when asked if it was acceptable to daub insulting graffiti on a politician’s home. Only 1% deemed that behaviour “completely understandable”.

We had asked people to rate the behaviours according to how acceptable and how understandable they are in order to avoid them feeling pressured to give a socially acceptable answer. Asking if something is understandable gives more space to indicate lenience towards threatening behaviour without appearing to condone it. Even on this softer measure, there is widespread public rejection of abusive or intrusive behaviours.

What about politicians we don’t like?

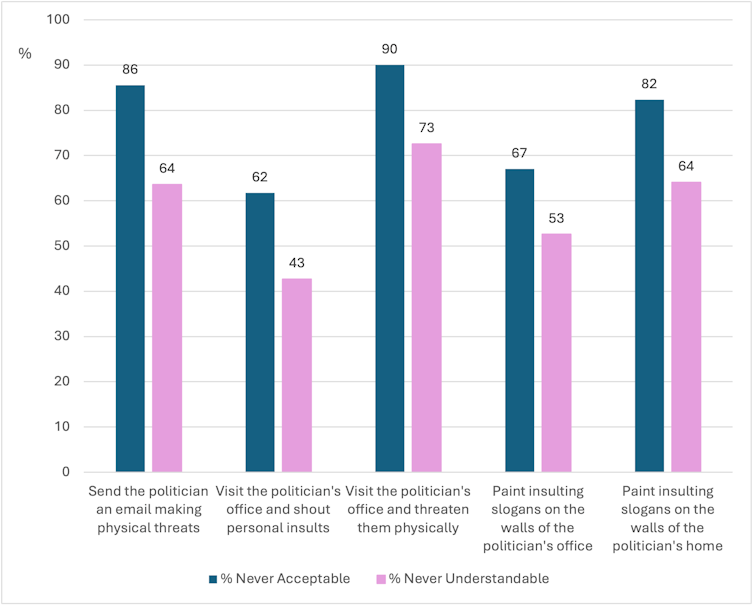

A key element of our survey was a primer that sought to find out if a person would feel OK about abuse towards a politician they don’t like. Before questioning them, we showed participants a screenshot of an exchange on X (formerly Twitter), in which a politician’s fairly strident comment about immigration provokes a hostile online response. For some respondents, this was a pro-immigration statement, for others it was anti-immigration. By factoring in the respondent’s own position on immigration, we know whether they were predisposed against this politician.

We found that even in cases where people disagreed with the politician, the “never acceptable” ratings were consistently very high.

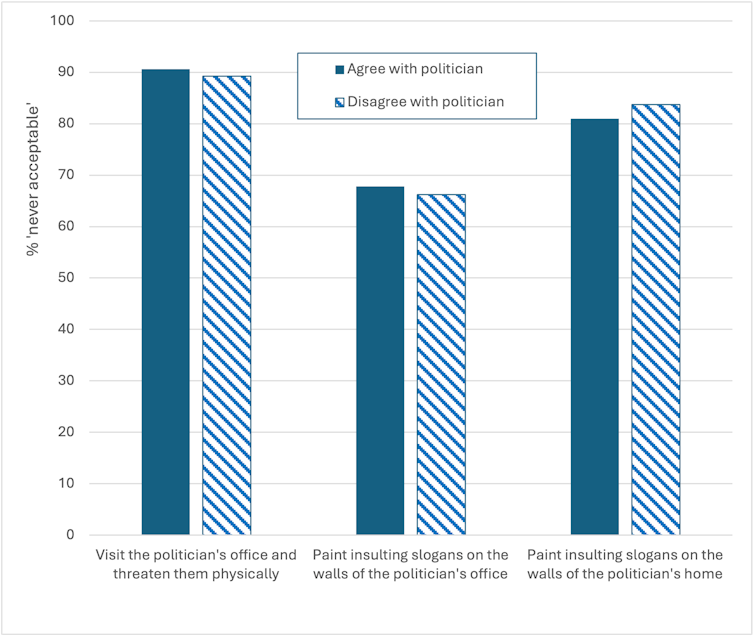

However, disagreeing with an MP’s views does make people a little more tolerant of online threats against them. Those hostile to the politician’s tweeted position were a little less likely to agree that people should intervene in the discussion when they see threatening comments being made online. They were a little more likely to agree that politicians can’t complain about being threatened online and that such threats are part of politics. But these differences, while statistically significant, are small. There is still widespread rejection of even online hostility.

Of course, there is a glass-half-empty interpretation of these results. There is a minority of people who do not condemn violent threats or vandals. And that minority would probably be rather larger were it not for the social pressures involved in taking even an anonymous survey. But the findings do appear to echo previous research that shows tolerance of political violence had much more to do with people’s general personality and their personal intolerances than any specifically partisan polarisation or hostility.

![]()

This article is based on research carried out in collaboration with Grame Davies, University of York. Sarah Yi-Yun Shair-Rosenfield does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Reed Wood and Rob Johns do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.