Many casual readers of the financial press will have learned a new term in the past few days: the “carry trade”. This is the culprit for the rollercoaster state of markets, many market commentators and journalists have opined.

Indeed it also played a role in kicking off the credit crunch and resulting global financial crisis in 2007-08. Should we fear a repeat? The answer this time is both yes and no.

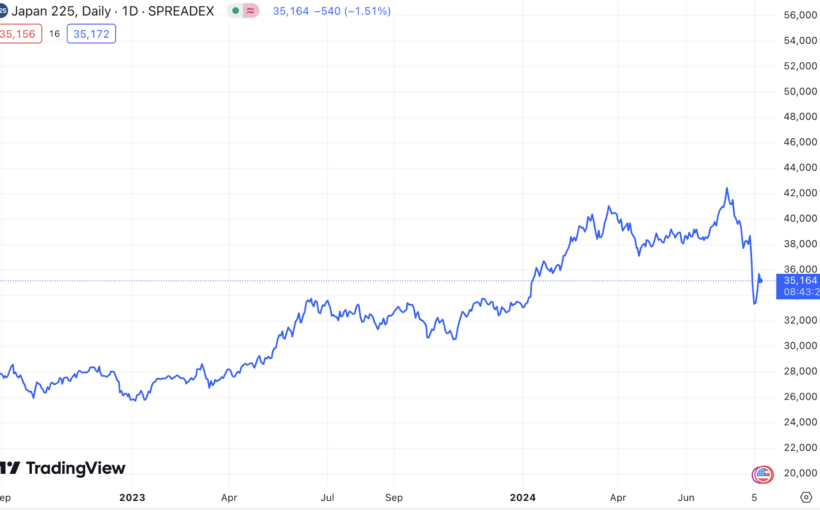

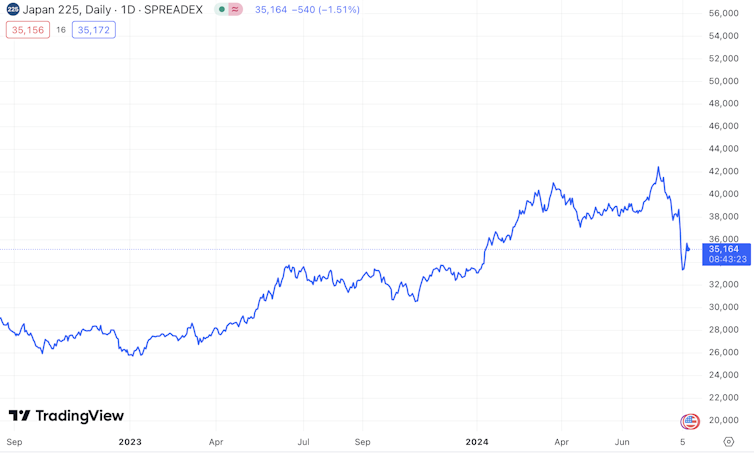

The current rumpus started on Friday August 2 when markets in America dropped in response to worse-than-expected data on the number of new jobs created in July. Then Japanese stocks took a bigger battering on Monday, posting the biggest ever one-day drop in the Nikkei, the country’s main share index. Since then, markets have gyrated up and down as traders and investors attempt to understand what is going on.

So why has the carry trade got the blame? First, a quick explanation of how it works. The carry trade is a financial strategy used by professional investors and also amateurs in the currency market to make money from differences between interest rates in different countries. Investors borrow money in a currency with a low interest-rate and invest it in a currency with a higher interest rate to make a profit.

Investors had been going to town with this strategy in recent years, borrowing cheaply in Japan in yen, where interest rates are still low (0.25%), and investing in place where rates are higher, such as the United States (5.25%-5.5%) and Mexico (10.75%). Researchers at Swiss bank UBS estimate that since 2011, more than US$500 billion (£392 billion) in US dollar-yen carry trades have taken place.

Nikkei average, 2023-24

It is possible to make a huge amount of money steadily from these interest-rate differentials on borrowed money, without putting any of your own capital at risk up front. But it is rather like collecting a line of pennies in front of an approaching steamroller: from time to time, carry crashes occur as currencies or interest rates move in a way that makes the trade unprofitable.

At this point, capital flows stop. The asset bubbles, which had been inflated in value by these cross-border flows, then pop. This spreads contagion around the financial system and affects the availability of credit for those in the trade: once even minor losses start to mount up, lenders begin to demand that these investors pony up more cash to cover their potential losses.

This process took off in the past few days and is one explanation being given for why Japanese investors dumped their country’s shares so rapidly, taking the entire world stock-market with them.

Carry trades and financial crises

Financial history supports the idea that we should be worried about these carry crashes. My latest book about the history of financial crises, Calming the Storms: the Carry Trade, the Banking School and British Financial Crises Since 1825, shows how they have been involved with every major banking crisis in Britain over the past 200 years.

The yen-dollar carry trade also played a role in triggering the global financial crisis of 2007-08. In 2009 a paper by economists at the Bank for International Settlements, a global network of central banks, found that the withdrawal of yen funding from America by carry traders coincided with the start of the credit crunch in August 2007, in which lending suddenly became unavailable across the financial system.

This contributed towards falling asset prices for assets such as collateralised debt obligations (CDOs), which are bundles of debt that were sold on by lenders into the market. These had previously attracted investment by carry traders, but this dried up and generally contributed to a lack of funds for banks to finance themselves with. This continued into the latter half of 2007 and into 2008 as the credit crunch developed into a full-blown financial crisis.

But while we should be worried about the carry trade, a softer landing is likelier than 2007-08. The narrowing of the difference in interest rates between Japan and America has been slight in recent days. The previous gap of more than 5% has only narrowed by 0.15%. It is only when interest rates between countries converge more closely that you should really panic.

In any case, in retrospect, the current market meltdown looks like it was triggered more by the poor American jobs data than Japan’s decision to slightly raise official interest rates. And those jobs numbers showed a mixed picture rather than being unremittingly terrible. It is far from certain that the US is heading into recession, implying that investors may have sold down stocks more than is warranted.

The events of the past week should be seen as yet another one of the market blowups that have occurred as a result of interest rates across the world rising rapidly in 2022 and 2023, a source of financial fragility. These include the panic triggered by Liz Truss’s mini-budget in Britain in September 2022 and the failure of Silicon Valley Bank in America in March 2023.

More ructions are likely, though hopefully none the size of the 2008 financial crisis. If you’re involved in financial markets, either as investor or investee, the wild ride is not over yet.

![]()

Charles Read's research is funded by a British Academy postdoctoral fellowship grant.