Iran is going to launch a retaliatory strike against Israel for the dual assassinations of Hamas leader, Ismail Haniyeh, on July 31 and Hezbollah’s number two, Fuad Shukr, just hours before. The only questions are when, where and how far will Iran go, which leads to its own supplemental question: how dangerous will this situation now become?

Iran’s intention to retaliate was announced on July 7 by acting foreign minister, Ali Bagheri-Kani, at an extraordinary session of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation in Saudi Arabia. Bagheri-Kani told the meeting: “In the absence of appropriate action by the [United Nations] security council against the aggressions and violations of the Israeli regime, the Islamic Republic of Iran has no choice but to exercise its inherent right to legitimate defense against this regime’s actions.”

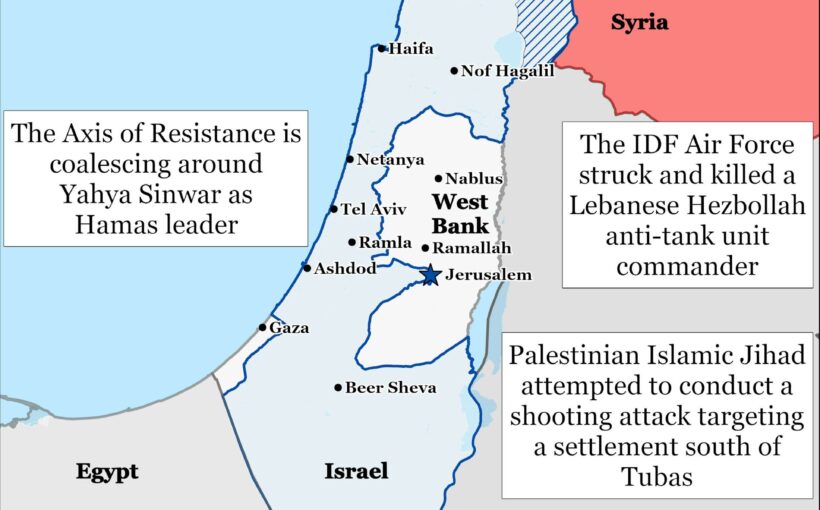

Israel is convening an emergency meeting of its security cabinet to discuss how to prepare for this retaliation. According to Middle East analysts at the Institute for the Study of War, this is being made more difficult for Israel’s security agencies by Iran’s armed forces media which is publishing a range of different information. The aim, they believe, is to “decrease Israel’s ability to effectively defend against an Iranian attack by causing Israel to disperse its air and missile-defense assets”.

Against this backdrop, the bloody nature of the war in Gaza looks certain to continue. Where Haniyeh was the pragmatic face of Hamas, his successor, Yahya Sinwar, is widely understood to be the architect of the October 7 attacks and is viewed as one of the group’s most extreme figures. He has, after all, spent 23 years of his life in Israeli prisons and has been directing the operations of militants inside the Gaza Strip since the start of the war.

According to Leonie Fleischmann of City, University of London, Sinwar’s appointment sends a clear message to Israel that killing the group’s leaders will not weaken Hamas but will instead strengthen its resolve to hold on to Gaza and continue engaging in a violent struggle.

With Sinwar taking the reins, a ceasefire in Gaza looks to have become even more remote – he reportedly has closer ties to Iran and is more aggressive than other Hamas leaders. But, in Fleischmann’s view, the fact that ceasefire hopes have been dimmed are not entirely surprising when you take the position of the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, into account.

Netanyahu has been regularly criticised, from both inside Israel and more widely, for prolonging the assault on Gaza in order to ensure his own political survival. His apparent sanctioning of Haniyeh’s assassination – Israel has not claimed responsibility for the killing – may have been yet another attempt to derail the ceasefire negotiations, Fleischmann says.

This is a view shared by Scott Lucas, an expert on international politics at University College Dublin. He argues that the war has landed Netanyahu in deep trouble. Netanyahu has so far failed on his pledge to “destroy” Hamas, and Israeli troops appears to be stuck in perpetual operations in full view of a mainly disapproving world.

The high-profile killing of “enemies” in Haniyeh and Shukr may have bought Netanyahu some time, he says. But it’s a gamble for the Israeli prime minister. The political dynamic in Washington – once Israel’s most staunch friend – shifted when the US president, Joe Biden, a longtime and stalwart supporter, announced he would not contest the next election.

A lot will depend on who wins in November. As we have reported here, Biden’s replacement at the top of the Democratic Party’s ticket, Kamala Harris, has a far more nuanced attitude to the conflict in Gaza and has already publicly declared that she wants a ceasefire sooner rather than later, with a two-state solution firmly on the table.

Strike on the Golan Heights

Over the past ten months, as the conflict in Gaza has raged, Israel (and the US) and Iran (and its proxies in Yemen, Iraq, Lebanon and Syria) have also engaged in a sporadic, tit-for-tat series of strike and counter-strike. Most of this has been carefully calibrated to keep the hostilities alive, while avoiding escalation into all-out war, something neither side has wanted.

But the rocket which hit a football game in a village in the Golan Heights on July 27 changed all that. The strike killed 12 children and teenagers, all between the ages of ten and 20, injuring at least 29 others. Erika Jiminez, Leverhulme early career fellow at the School of Law, at Queen’s University Belfast, who has been conducting research in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, warns that it has greatly increased the complexity of the situation.

Israel captured the Golan Heights from Syria after the six-day war in 1967 and has occupied the strategically important region ever since, declaring the rocky 1,000 square kilometre plateau to be part of Israel in 1981. The vast majority of the Syrian population fled in 1967, but about 20,000 inhabitants remained – mainly Syrian Druze people. The Druze are a minority Arab sect with about a million members spread across the Middle East, who don’t believe in inter-marriage and don’t allow outsiders to join the religion.

As Jiminez explains, despite being given Israeli identity papers, they have steadfastly refused to take up Israeli nationality. But notwithstanding, Netanyahu lost no time in blaming Hezbollah for the attack and vowed they would pay a “hefty price”.

On a knife edge

Whether we will now see a wider regional conflict is difficult to say: all parties are making ominous noises. But, according to Ian Parmeter of Australian National University, the death of particularly Haniyeh is likely to have caused enormous anger in Iran and it has pushed the whole region onto a knife’s edge.

In his view, Iranian retaliation is most likely to come through Hezbollah. But Parmeter says that Iran also has other allies on which it can call, including Shia militant groups in Syria and Iraq, as well as the Houthi rebels in Yemen.

We’ve seen that Iran has declared its intention to seek revenge for the assassinations. The question now remains when it will come and what will be the consequences.

![]()