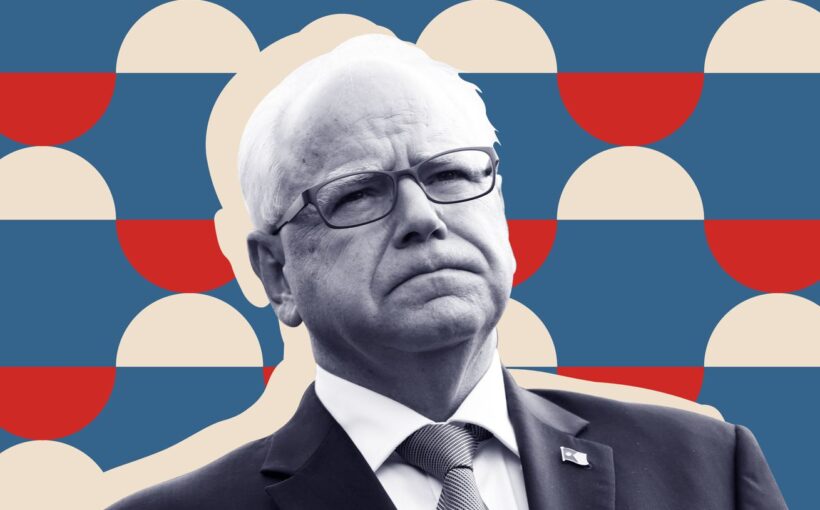

Last year, when Minnesota’s progressive politicians coalesced around a bill to raise the minimum pay for Uber and Lyft drivers in the state, their ostensibly left-of-center governor surprised them all by pulling a move he had yet to use while in office: he vetoed it.

Uber and Lyft were threatening to stop operating in Minnesota if the bill was signed into law, and Governor Tim Walz was worried about losing a mode of transportation that many Minnesotans relied on. But he also didn’t want to ostracize his progressive allies, many of whom have been laboring for years to force the multibillion-dollar ridehail companies to cough up a little more for their beleaguered drivers.

Now that he’s been catapulted to the national stage as Vice President Kamala Harris’ running mate, it’s worth reexamining how Walz navigated a tricky situation with two major tech companies and their progressive opponents — and how the ultimate solution left some major issues around the gig economy unaddressed.

“I think these workers, these drivers in the gig economy — we’re looking at a brand new model of how things are done,” Walz told a local reporter in May 2023 after vetoing the initial legislation. “They’re independent contractors and I think there’s no doubt about it, there’s got to be some protections. There’s gotta be minimum wage, there’s got to be protections on how they get deactivated. So I’m in agreement with them. I don’t believe the vehicle that passed the legislature at the very end was the vehicle to do that.”

Supporters of the bill expressed their disappointment. The Minnesota Uber/Lyft Drivers Association said on X (then Twitter), “It is surprising that [Tim Walz] sides with corporates [sic] over poor drivers who campaigned and voted for him like he would be their savior.”

But their disappointment would be short-lived. A year later, Walz signed a bill into law that would raise pay for drivers by an estimated 20 percent while also providing a new type of insurance for injuries incurred on the job and making it harder for Uber and Lyft to deactivate drivers from their respective platforms.

Walz proved deft at handling the issue, signaling to Uber and Lyft that he was willing to compromise while also keeping progressive groups at the table. He formed a working group that was tasked with gathering data on driver pay and corporate profits, among other elements. To be sure, the new law didn’t raise driver pay as much as the original proposal — $1.28 per mile and 31 cents per minute, versus $1.40 per mile and 51 cents per minute.

But it seemed to work. Uber and Lyft backed off their threat to leave the state. And Minnesota gained the distinction as only the second state in the US, after Washington state, to regulate rideshare driver pay through legislation. (New York’s attorney general announced minimum pay rates for drivers as part of a settlement with Uber and Lyft last year.)

Walz used the opportunity to tout his commitment to raising standards for working-class people while keeping transportation prices low for regular Minnesotans. “The idea that if you put in a hard day’s work, you get paid a fair wage for it,” he said at the bill signing ceremony on May 28th. “That at work you should be safe, you should be taken care of, and that we’re providing a service that Minnesotans depend on.”

The new law also requires Uber and Lyft to provide insurance to drivers that goes beyond what’s already covered by their car insurance. (Drivers wanted insurance to cover injuries from assaults from riders, for example.) It also restricts how Uber and Lyft deactivate drivers from their platforms.

But there are also some big pieces missing from the bill, such as anything that would require Uber and Lyft to classify its drivers as employees rather than independent contractors. Driver groups and labor organizers have been pushing states to reclassify drivers as employees so they can qualify for certain legal benefits, like minimum wage, overtime pay, unemployment insurance, worker’s compensation, and paid sick leave.

Uber and Lyft are extremely intent on keeping drivers as contractors. And Walz proved unwilling to tackle that particular issue, perhaps realizing that the courts would be the ultimate arbiters.

Several courts have already weighed in on the debate, most notably in California, but Uber and Lyft have successfully beaten back such efforts through ballot initiatives. President Joe Biden’s Labor Department announced a final rule earlier this year that would make it harder to classify workers as independent contractors, effectively rescinding a Trump-era rule that would have relaxed those rules. But if Trump wins in November, those rules could swing back the other way.

In the end, he got his deal, and Uber and Lyft vowed to stick around in Minnesota, mollifying concerns. It’s unclear whether Walz’s involvement in any way played a role in his selection as the vice presidential nominee. After all, the Harris campaign has its own ties to the ridehail industry. Harris’ brother-in-law and top advisor is Tony West, who is also the general counsel at Uber. And the vice president recently hired David Plouffe, a veteran of the Obama administration and a former vice president of strategy at Uber, to help run her presidential campaign.

The deal won by Walz was not without its critics. Niko LeMieux, cofounder and COO of the Minnesota-based payments startup Easy Labs, criticized Walz for his dismissive attitude toward smaller rideshare companies that wanted to fill the vacuum if Uber and Lyft followed through on their threat to leave the state. Walz called the idea that any new app company could replace the rideshare giants “magical thinking,” but LeMieux argued that he was underselling the state’s entrepreneurial spirit.

But those criticisms were set aside when Harris announced Walz as her pick. Hours after the announcement, LeMieux posted a photo of himself on X with his arm draped around the governor and a big smile on his face. After all, the past was in the past. And Walz was on his way to bigger things.