Nature protection, conservation and restoration is “not a trivial matter but key to human survival,” according to scientists quoted in a 2005 UN report. To demonstrate this, they developed the concept of “ecosystem services” – the benefits that people derive from nature. Over the next 20 years, this concept has been in constant development to reflect our growing understanding of how ecosystems work and how we benefit from them.

For many people, it feels wrong to take a human-centred view on nature. But for governments and conservation organisations, this concept is a useful tool. It helps us quantify the value of nature and make sure certain aspects are conserved and protected.

My team and I provide other scientists with information about how coastal areas help to regulate the climate and reduce water pollution. In part, we work with marine conservation experts who restore ecosystems that have been depleted, such as seagrass or oyster beds. This can help choose the best approaches to restoring coastal areas to healthy habitats while providing other benefits, such as shelter for young fish or food for seabirds. Another group of scientists use our data to assess the value of these habitats, now and in the future once they have been restored to good health.

In my work as a marine ecologist, I split ecosystem services into three different groups. First, provisioning services include the provision of food or timber along many other material gains we get from nature. For marine ecosystem services ,this includes fish and chemicals used for research and medicines. Second, regulating services support our planet and human wellbeing. Mussels clean water by filtering it and seagrass takes up and stores carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, thereby helping to regulate the climate. Third, cultural services include leisure and recreation such as sea swimming or fishing.

Diving deeper

To better understand these marine ecosystem services and how to use them sustainably, my research delves into some of the more complicated processes that regulate ecosystem services. In terms of the ocean’s role in regulating climate, it’s not just about seagrass.

Seaweeds such as kelp take up carbon too, but cannot bury it in the soil beneath them due to holding onto rocks rather than having roots. They store carbon by getting buried in the deep sea when they are whipped off the rocks during winter storms and transported by currents into deeper waters. There, worms and crabs can feed on this important food source, drawing the carbon deeper into the sediment.

Another step is to measure the benefits of particular ecosystem services. Food provision can be relatively easily measured by data collected by harbours to quantify how much fish is being landed and sold. So we can estimate the volume of harvested fish and calculate their market value. Some cultural services, such as measuring the wellbeing benefits people receive from interacting with coastal environments, can be more difficult to measure.

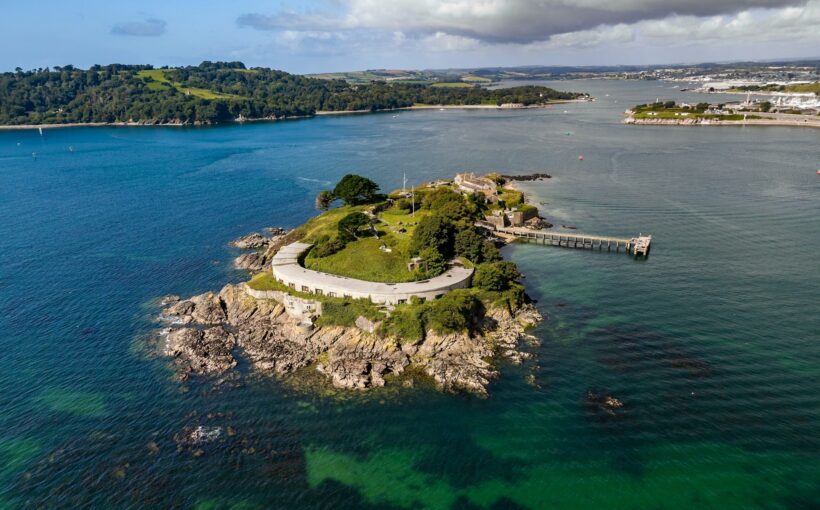

Plymouth Sound is a great place to assess both benefits to human wellbeing and marine ecology, because not only is this city a hotspot for marine biology research with three internationally recognised marine institutes, it’s also the UK’s first national marine park. Here, I can engage not only with the ecological sciences and datasets but also with environmental psychologists who study how nature affects us and how we affect nature. My team and I have created the marine, social and natural capital laboratory to explore this more.

Because of so many complex variables, it’s important that scientists like me choose the appropriate indicators to estimate the value of contributions from different ecosystem services. Then, we can assess whether interventions such as restoring seagrass or building a port might help or hinder the marine environment.

Often, different ecosystem services might interact or conflict with each other. Fishing in the northeast Atlantic might, for example, negatively affect marine mammals such as seal if the fish they rely on as food are also being eaten by humans. So we need to look at the bigger picture to assess all of the ecosystem services provided by a particular area of ocean. And as our understanding of ecosystem services develops, we can refine efforts to give nature a helping hand.

Swimming, sailing, even just building a sandcastle – the ocean benefits our physical and mental wellbeing. Curious about how a strong coastal connection helps drive marine conservation, scientists are diving in to investigate the power of blue health.

This article is part of a series, Vitamin Sea, exploring how the ocean can be enhanced by our interaction with it.

![]()

Stefanie Broszeit receives funding from the United Kingdom Research and Innovation and from Horizon Europe, funding European research through the European Commission.