Trust in Britain’s institutions is in bad shape, according to recent data from the European Social Survey.

Trust is important because a good deal of governing involves trying to persuade people to do things or convince them that things will get better in the future. This is increasingly difficult to do if trust is in decline. Trust in political institutions is particularly important when governments have to make unpopular decisions, such as raising taxes.

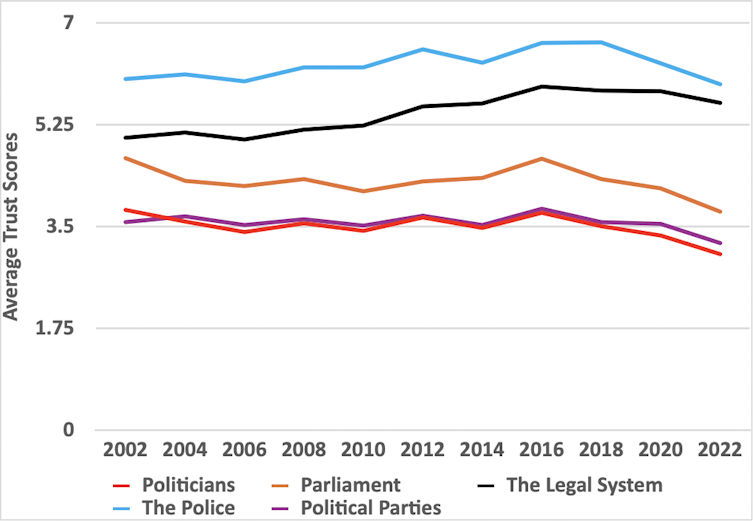

Data covering a 20-year period shows a marked decline in trust in parliaments, political parties and politicians. The following question is asked in the European Social Surveys over time:

Please tell me on a score of 0-10 how much you personally trust each of the following institutions. 0 means you do not trust an institution at all, and 10 means you have complete trust in it.

The decline in trust began around the time of the 2016 survey, when the lowest level of trust in politicians and political parties was recorded in 20 years of doing the survey. Parliament has done a bit better, but decline in trust for it is still quite marked. It is no coincidence that this decline started in 2016 – the year of Brexit.

Average trust scores for British institutions, 2002-2022

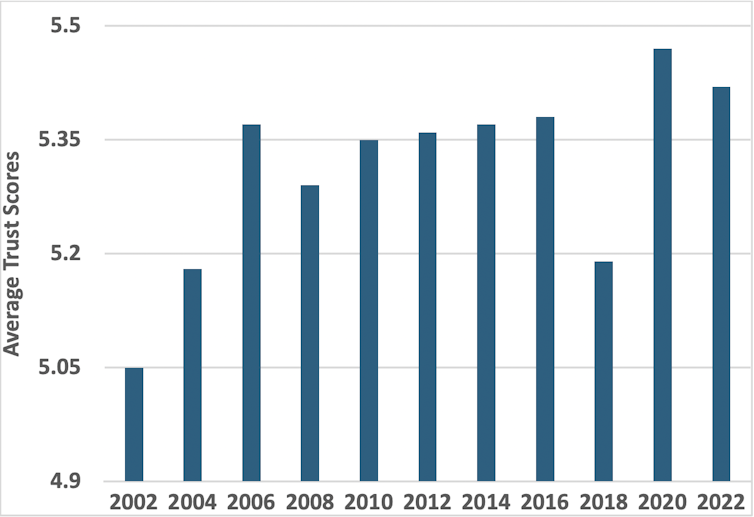

But the European Social Survey carries another important measure of trust – our trust in fellow citizens. A question in the surveys asks how trusting respondents felt about other people on an 11-point scale, with a high score indicating that people are trusting.

Average trust scores in other people in Britain, 2002-2022

After a shaky start at the beginning of the millennium, trust in other people increased significantly in Britain in 2006, to over 5.35 on the 11-point scale. It then dropped in 2008, the year of the financial crisis. The recovery from this decline was in place by 2010. It is noticeable that the trust scores fell again in 2018, when the political consequences of Brexit were making themselves felt. Trust revived again in 2020 during the pandemic.

So, our trust in each other is in healthier shape than our trust in institutions. This is important because trust in others is a key measure of social capital – the willingness of people to work together to solve social and economic problems in society. The importance of social capital in creating prosperity in the US was highlighted by the American political scientist Bob Putnam in his best-selling book, Bowling Alone.

There is now a large literature on social capital and trust, some of it focusing specifically on Britain. The findings are that trust promotes prosperity for a number of reasons. If people trust each other, they are more likely to volunteer. This free labour helps to provide a social safety net, which increases prosperity for all – even if it is not fully recognised in the national income statistics.

High-trust countries like Denmark and Sweden also have low levels of corruption – and corruption is a blocker to growth. In a high-trust environment, the costs of doing business are lower because there is less need for elaborate contracts, expensive lawyers and lots of litigation to make other people behave properly. This is, in part, why high-trust countries are richer than low-trust countries.

It’s well established that economic growth is driven by investment in innovation, skills and transport, extra manufacturing capacity and greater workplace productivity. However, it is also the case that social capital helps to create economic growth. In researching this across a variety of countries, I found that trust was very important in stimulating economic growth alongside these other factors.

Government has limited direct influence on social capital, but it can encourage it by investing in voluntary organisations and increasing transparency in its dealings with the public.

Britain has suffered from a lack of investment in capital spending and infrastructure, and has neglected investment in education over the past 15 years. Social capital seems to be in much better shape, and faced with the significant challenge of restoring growth, the UK government needs to pull every lever at its disposal. It can repair trust in politics with its own actions, and this is likely to help with sustaining social capital, which is part of the solution to restoring economic growth.

![]()

Paul Whiteley has received funding from the British Academy and the ESRC.