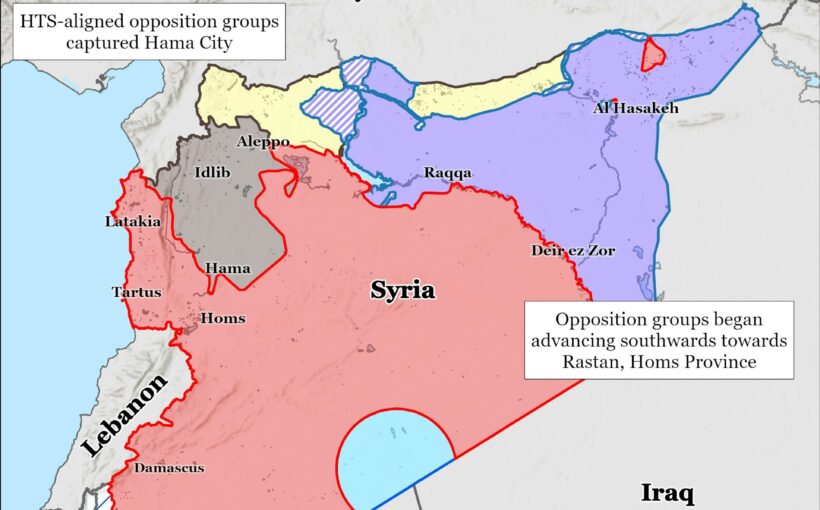

The lightning-fast capture, by Syrian rebels, of large swaths of northern Syria, including the war-torn country’s second-largest city, Aleppo, and the strategically important city of Hama further south, is a body blow for the regime of Bashar al-Assad.

The rebels are now pushing on further south towards my home city of Homs. When these cities fell to Assad – Aleppo fell in 2017 – it was seen as spelling the end of Syria’s popular revolt against the regime, which had begun with such optimism when Syrians poured on to streets across the country in 2011 to call for freedom, justice and dignity.

After decades of oppression at the hands of the Assad family, hopes for a different future were high. But hope quickly turned to despair. The peaceful demonstrations were crushed by the Assad government, sparking a brutal armed conflict that has killed half a million people and has displaced over 12 million more.

The war in Syria largely disappeared from newspaper front pages as the years passed. But, with the explosion of violence in the country over the past week, that has now changed.

For many Syrians, both in exile and inside the country, the rebel advance has reignited the hopes of 13 years ago. Many detainees have already been released from Syrian prisons and there is cautious optimism that displaced people and refugees may finally be able to return home.

At the same time, however, many Syrians are fearful of new wars yet to come, of new cycles of violence in cities and towns across the country, and of new sources of suffering, displacement and human rights violations.

Assad has vowed to “crush” rebel forces, and his key allies Russia and Iran have offered their “unconditional support”. Since November 27, when the rebel offensive began, almost 300,000 people have been displaced and hundreds have been killed. Fighter jets have intensively bombed rebel-held areas, hitting residential buildings and even a hospital in Idlib in northern Syria.

In a speech made at the UN security council in New York on December 4, Raed Al Saleh, the director of Syria’s White Helmets civil defence, also spoke of his grave concern about the “real threat of chemical attacks”. Civilians, particularly those in rebel-held areas, again find themselves trapped in the heart of the battlefields.

But it’s not just further waves of violence that Syrians are worried about. Since 2011, life has become a battle in itself to access basic necessities. And things are now becoming harsher.

The prices of essential commodities in Aleppo, as well as other cities, have risen significantly since the rebel takeover, with residents reporting that some goods have doubled in price. In a country where around 90% of the population are already living in poverty, more instability will only make life harder for people already struggling to get by.

Fears of an uncertain future

There are also fears that if rebel groups control further parts of the country, there will be more restrictions on freedom. Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the Islamist militant group at the centre of the offensive, was originally formed out of an al Qaeda affiliate. But the group has rebranded itself in recent years.

Its leader, Ahmed Hussein al-Shar’a, who is known by the nom de guerre Abu Mohammad al-Jawlani, is putting himself forward as a champion of pluralism and tolerance. HTS is now calling for a “Syria for all Syrians”, aiming to gain broad public support from a population of diverse religions and sects.

In an exclusive interview with CNN on December 6, Jawlani was asked whether Christians and other religious and ethnic minorities would live safely under the rule of HTS. In response, he said: “no one has the right to erase another group. Each sect has coexisted for hundreds of years, and no one has the right to eliminate them.”

But, notwithstanding this, many Syrians living outside the country have expressed concern for the future following the rebel advance. In an interview released on December 4, Mehdi Hasan, a British-American journalist, discussed how HTS has modelled itself on the Taliban in Afghanistan.

“What a lot of supporters of the Assad regime say is that if this group is allowed to take over Syria, it will be like the Taliban. You will have women oppressed, you’ll have Christians persecuted, you’ll have Shias, minority groups targeted”, Hasan remarked. “Is that true right now? Is that the case?”, he questioned. Hassan I. Hassan, a Syrian-American journalist, replied: “It is true. And it is the biggest fear”.

These fears are rooted in the human rights violations that have been perpetrated by HTS in the areas under its control. In 2023, Amnesty International warned that HTS was subjecting journalists, activists and anyone who criticised its rule in Idlib province to “arbitrary detention without access to a lawyer or family members”.

One year earlier, the UK-based Syrian Network for Human Rights released a report attributing the deaths of at least 505 civilians between 2012 and 2021, including 71 children and 77 women, to the HTS. In his interview with CNN, Jawlani admitted that there “were some violations” against minorities by “certain individuals during periods of chaos”. “But we addressed these issues”, he went on to add.

A video on X (formerly Twitter) shows a Muslim woman asking a man in Aleppo whether he is Christian, and how his situation is after the rebels captured the city. A coordinated PR campaign seems to be accompanying the offensive to assure people of their safety and that life is continuing as normal after HTS gained control.

This is in contrast to areas controlled by other radical groups, such as Islamic State, where people have been killed over their beliefs or religion.

Syria once again finds itself at a crossroads. And no one knows what might happen next. Rim Turkmani, a senior research fellow at the London School of Economics, believes that a “legitimate political solution that really involves all actors on the ground” is the only thing that will bring peace to Syria.

After 13 years of exile, displacement and mass killing, we Syrians need this peace. But for now we need a miracle. Voices of wisdom, unity and calmness must prevail to prevent Syria from falling into another period of grief.

![]()

Ammar Azzouz conducts his research as a postdoctoral fellow, funded by the British Academy.