This article was first published as World Affairs Briefing from The Conversation UK. Click here to receive this newsletter every Thursday, direct to your inbox.

Waiting for news this week of whether a ceasefire deal between Hamas and the Israeli government must have been agonising for the people of Gaza and for the families of hostages taken in the attack of October 7. All week the talk was that a deal was in the very final stages of negotiation. It would be soon, we were told.

By Wednesday morning, the BBC was reporting that negotiators from Israel and Hamas were “in the same building for the first time” as the final details were ironed out. That afternoon, the Qatari government in Doha, where negotiations have been based these past 15 months, announced that the prime minister, Sheikh Mohammed al-Thani, would hold a press conference. It was on.

Then a flash from Associated Press: talks had hit a last-minute snag and Israel was blaming Hamas. It was off, despite Hamas insisting they had accepted the deal.

Then it was back on. Then it was off again. These mixed messages had become so frequent it’s hard to think this wasn’t a negotiating tactic of some kind. At one point, an Israeli official had barely had time to confirm that the two sides had agreed an “outline deal” for a ceasefire and return of hostages when Netanyahu’s office issued a denial, saying a deal hadn’t been done and Hamas was to blame. It was an indication of how precarious things still were.

But as the clock ticked in Doha, people were dying in Gaza. Scores of civilians were killed in airstrikes overnight on Tuesday. Scores more were killed on Wednesday.

Sign up to receive our weekly World Affairs Briefing newsletter from The Conversation UK. Every Thursday we’ll bring you expert analysis of the big stories in international relations.

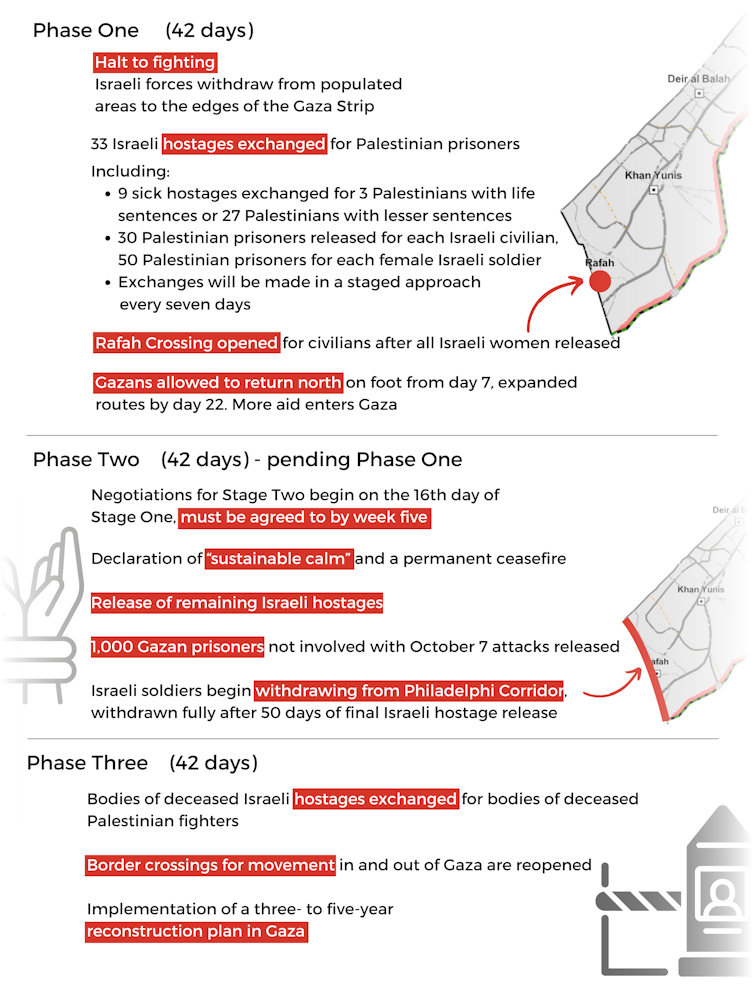

Then, at just after 5pm GMT, Donald Trump took to his social media platform, Truth Social, announcing “WE HAVE A DEAL.” At almost the same time, Qatari officials as well as Hamas and Israel confirmed that a deal had indeed been signed. The ceasefire would begin on Sunday and a timetable for the release of hostages had been agreed.

There was, it seemed, a glimmer of hope for the people of Gaza and the relatives of the Israeli hostages, some of whom have been waiting for 15 months to hear news of their loved ones. Images began to appear on the international news wires of celebrations in Israel and Gaza, where ordinary people on both sides of this tragic conflict wept with relief.

Amid all the confusion, Scott Lucas, a Middle East expert at University College Dublin, who has been covering this conflict for decades, was in constant touch with The Conversation’s international affairs team. We had prepared a number of questions to give a sense of the background to the deal – which he says is virtually identical to one that nearly got over the line last September.

A Lucas points out, last September the deal reached the stage where Israel’s chief negotiator, Mossad director David Barnea, had said a deal was just about to be done only for Netanyahu to change Israel’s list of demands at the last minute. Something in the mixed messaging on Wednesday suggested there was now a similar situation at play.

Lucas cautioned that, whatever was said in Doha, it was what would be said in Israel that would count, as Israel’s domestic politics took centre stage. The detail wouldn’t be done until Netanyahu had the agreement of his cabinet, which was due to meet on the morning of January 16.

Which is where it still stands as I write. Netanyahu’s powerful ultra-nationalist allies Itamar Ben Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich remain determined to scupper the deal. The cabinet meeting has been postponed and airstrikes continue in Gaza, killing dozens of people who had been hoping their ordeal might be over.

Read more: Gaza: seven big issues affecting the delivery of humanitarian aid

As for Sunday’s ceasefire? The US says it is confident it will go though. But Marika Sosnowski, a security expert at the University of Melbourne specialising in the Middle East, cautions that this agreement will neither end the war nor bring a lasting peace: “Ceasefires are not a panacea for the war, trauma, displacement, hunger and death Israelis and Palestinians have borne before and since October 7, and will no doubt continue to bear, long after.”

Sosnowski calls the deal a “strangle contract” – the sort of arrangement where one side is far more powerful than the other. And the three-stage agreement even mandates for further negotiations towards the end of stage one in order to agree on what happens in stage two.

The war between Hamas and Israel is not over, she writes. “This ceasefire simply marks the start of a new phase.”

Humanitarian aid

But let’s assume that the agreement gets over the line in Israel and a ceasefire begins on Sunday, giving the estimated 1.9 million Palestinian civilians who have been displaced over the past 15 months the chance to pick themselves up and make their way home to try to rebuild their lives. They will do so in the middle of a humanitarian crisis.

Sarah Schiffling, deputy director of the Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management Research Institute at the University of Hanken in Finland, walks us through the challenges ahead. The people of Gaza, she writes, have virtually no food or medical supplies. They have no fuel. Many, if not most, of their homes have been destroyed. There is no agriculture or industry left, and it will take years, if not decades, to recover.

Most warehouses have been destroyed and many of the roads on which aid agencies will depend to get the food and supplies to those in need will have to be repaired. Meanwhile law and order is non-existent, making the delivery of aid doubly difficult in a region where everybody is desperate. There will almost certainly be looting.

And, unless it changes its mind, Israel is about to impose a ban on its authorities working with the largest UN organisation in Gaza, the United Nation Relief and Works Agency (Unrwa) on the grounds it has been colluding with Hamas. This will make it nigh on impossible for the agency to negotiate safe movement around the Strip.

But agencies like Unrwa cannot hope to make a difference unless there is lasting peace and people of Gaza are given the chance to recover from the trauma and the help (and the unimaginably large amounts of money) to try to rebuild their lives.

Read more: Gaza: seven big issues affecting the delivery of humanitarian aid

Trump world 2.0

As we’ve already seen, the US president-elect was quick to trumpet his involvement on getting the deal over the line. He followed his initial post with several more, proclaiming shortly the deal was announced that: “This EPIC ceasefire agreement could have only happened as a result of our Historic Victory in November.”

When Trump’s claim was put to him at a press conference later the same evening, Biden seemed amused: “Is that a joke?” he asked, before explaining that any deal would need the full engagement of the US government, which is why he had instructed his team to work closely with Trump’s, “because that’s what American presidents do”.

More generally though, something that US presidents haven’t often done in the past is to threaten their closest allies the way Trump has the leaders of America’s fellow Nato members. You’ll recall that during last year’s election campaign, Trump said he would encourage the Russians to do “whatever they hell they want” to any Nato members not paying their bills.

The incoming president returned to that theme last week, telling a press conference that he expected Nato members to increase their defence spending to 5% of their GDP. To give this some context, in 2014, Nato set a 2% figure with a target date of 2024 to reach it.

Trump’s demands have galvanised Nato’s politics, writes Birmingham University’s Mark Webber, an expert in Nato politics. As Webber notes, this has gone down well with countries such as Poland and the Baltic states, which sit nervously in Russia’s back yard and have already begun to significantly increase their defence spending.

Not so much countries such as Italy, Spain, France and Germany, who may well struggle to meet this target. Germany even has legal constraints about the amount of money it can spend on defence, notes Webber.

As for the UK, despite Keir Starmer’s pledge for a Nato-first defence posture which includes a “cast-iron commitment” to increase defence spending, the current plan is to get to 2.5% of GDP by 2030/31. And it doesn’t look as if there’s a great deal of budgetary headroom to go much further much quicker.

Read more: Nato: why the prospect of Trump 2.0 is putting such intense pressure on the western alliance

Meanwhile, on the home front, the US president-elect has been able to draw a line under the legal proceedings that have dogged him since January 6 2021. The two-year investigation into the assault by Trump supporters on the US Capitol has been closed down and Jack Smith, the justice department official who so doggedly pursued the investigation into the incoming president’s part in that sorry episode, has resigned.

All that is left for the public record now is the part of the written report pertaining to that investigation, which Smith said in the report would have been enough to secure his conviction had he not won the election. Emma Long, an expert in US politics and history at the University of Essex, has the story.

She reflects that while most Americans have always held the rule of law close to their hearts, the fact is that 77 million people voted for Trump despite knowing about January 6. Smith’s report, she says, is a “a call to the better angels of American nature, a reminder to citizens of the higher principles to which the nation has historically pledged”.

She concludes: “If Americans ultimately choose the Maga way instead, the nation – and the rest of the world – will feel the consequences.”

Read more: Trump’s election interference case may be closed, but it still matters for America’s future

World Affairs Briefing from The Conversation UK is available as a weekly email newsletter. Click here to get our updates directly in your inbox.

![]()